Human Resource Management in Higher Education

Higher education institutions as learning organisations

Vesna Holubek and Patrik Punčo

Introduction

Human society can be considered a living organism that changes as time passes (Schön, 1973) and that has character of unpredictability (Iandoli and Zollo, 2008). The same is valid for organisations hence also for Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). They are a subject to constantly changing environment where the whole system of factors is once dominated by some attributes and another time the context has changed. On the other hand, the HEIs are also part of the system and interact with their environment on national and international levels.

The HEIs that conceived this ever changing nature of life understand that their operation is a subject to constant change too. The change context in the Higher Education (HE) sector has definitely different dynamics than the industry; however the overriding assumption of changes is valid by default. They must acknowledge that they need to adapt to new conditions and possibly also create better conditions for their own and society's future. We call the process of adaptation and interaction in the system and what it requires in the paper organisational learning. Organisations that mastered this skill are called learning organisation.

The paper is divided into two parts. The first part will give a general introduction to learning organisation definition. The second part is dedicated to the potential of HEIs to become learning organisations.

The Concept of Learning Organisation

Organisations throughout the time of operation come across different obstacles and sometimes they fail. Whether they realise or not they learn using the organisational memory and experience that comes with practice. According to one of the most renowned authors on the topic of learning organisations, Senge, (1994, p. 20) “The most powerful learning comes from direct experience”. And often the best solution for a problem comes built within the obstacle that created the problem.

The concept of learning organisation is closely related to the concept of learning society developed by Schön (1973). It links the need to learn to the experience of environment that implies change. Stable state is an illusion that blinds the society, in reality there is only constant change that calls for constant transformation. This is valid not only for the society but for the organisations as well. Schön (1973) points out that we need to learn to understand, adapt, influence or even manage these transformations. This idea implies the establishment of the notion of learning systems that enable continuing transformation.

The definition of a learning organisation according to Senge (1994, p. 3), is as follows: Learning organisations are “organisations where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning to see the whole together”.

In his definition above we can see two crucial points. First of all, the learning organisation is based on human factor; employees attributed specific capacity of being allowed expansive thinkingness which leads towards organisational learning. This means that, regardless the size of the organisation, the Human Resources (HR) attitude represents a crucial role in the success of creating organisational environment that is able to learn. And secondly, we need to acknowledge the fact that the organisation operates in a system where all the individual players and factors are interconnected and subject to change. This notion is the first step towards becoming a learning organisation.

Senge (1994) further in his work establishes the conceptual framework of the learning organisation theory by defining the five disciplines that represent the cornerstones of his arguments. The disciplines are as follows: systems thinking, personal mastery, mental models, building shared vision, team learning. In the next paragraph we will explain these terms.

Personal mastery refers to a significant level of proficiency in a specific domain. People who achieved personal mastery are capable to deliver consistent output and become interested in their own learning in long term. Personal mastery addresses looped personal vision profiling and seeking objectives. Senge (1994) objects here that few organisations encourage their employees to reach such a level of professional proficiency. Furthermore, the author suggests that personal learning and organisational learning are interlinked.

Mental models are the assumptions, generalisations and images of desired behaviour. The idea of using the mental models concept is to realise them, so they can be modified and changed towards a better performing model. It calls for an open attitude in conversations with employees dropping criticism of their exposed thinking, but rather taking it as the mirroring of the internal settings of the models that work in the organisation.

Building shared vision is a powerful performance tool. It’s a picture of the favourable future that is shared within the organisation. The vision needs to be well translated and operationalised in order to take effect. It needs to be mentioned nonverbally and verbally, often. Its effect might be supported by a charisma of the leader.

Team learning suggests thinking together. Teams are fundamental learning units in an organisation, not an individual.

Senge puts a special emphasis on the system thinking principle, which he calls the fifth discipline, because it is essential that all the disciplines evolve together as a whole, to be able “to see the trees and the forest”, a case when the synergy effect pays off more than applying the instruments separately. (Senge, 1994)

Senge´s argument for why learning organisation is an important concept is to gain and sustain competitive advantage by learning initiatives quicker than the competition. The work of Iandoli and Zollo (2008) discusses the value created by the learning. Learning organisation has a competency building potential that further produces strategic options, importantly, more than the organisation will be able to exploit. Learning organisations are also able to leverage the developed competencies by implementation and exploitation of the available tools and possibilities.

The problem with building competencies via learning within the organisation is that it is not possible to identify, control and develop the competencies by regulations and by directives. They usually emerge in the common workplace and the organisation learns to integrate them organically in order to benefit from this new ability. It is rather not possible to conserve the essence of learning organisation, the potential to create competencies that present future value, in rigid policies and procedures. Iandoli and Zollo (2008) explain that “learning and competencies building are collective processes based on mutual agreement and reciprocal adaptation”. But, as they developed further in their work, they say that learning as collective action is almost always perceived as anomaly and an attempt to “question the status quo” creating a resistance effect on different layers of the organisation.

Naturally, there are also some critical responses to the concept of learning organisation. According to Coopey (1995) there are three main downsides of the concept. The first argument outlines the fact that learning organisation in practice has a political context which is not reflected upon in literature; consequently political activity tends to affect learning goals. Furthermore, in practice, the model of learning organisation does not yield empowered employees to extent suggested by theory because it is in contrast to the managerial resources and informational power position. The last critical point is that the learning organisation is based upon managerial perspective leaving the space for neglecting the position of employees and importing certain ideological preferences.

Here the question is in what scope and depth the HEIs are able and willing to allow such a building processes to take part? At least some of the HEIs are significantly regulated by policies of state or of the rectorate, and even the immense funds cutting trends in HE sector (de Boer et al., 2008) do not provide a fertile ground for such initiatives. On the other hand, the entrepreneurial university like the University of Twente in Netherlands can serve as a good example that the learning at HEIs is also possible. In the relatively small area of Netherlands, the universities have created highly networked knowledge hubs where the HEIs do take notice of the new trends and thinking and are able to incorporate them into building new competencies, like spin-off centres and new educational market exploring, for instance LLL (Life Long Learning).

We mentioned the importance of experience in learning. A concept that is very closely linked to learning organisation and organisational change is the organisational memory. Organisational memory according to Iandoli and Zollo (2008) is a system of shared values and artefacts that suggest the way of common behaviour. They call the relationship between the organisational change and organisational memory the organisational learning. As a contrary to organisational memory there is organisational forgetting. It occurs according to work of Argote (2013) when people leave the organisation, files get misplaced or the technology gets obsolete. The assumption that organisational learning is cumulative, and it persists, might not be hold as true and instead the created knowledge may be a subject to depreciation. These ideas of organisational forgetting and knowledge depreciation are supported in the work of Argote (2013) by empirical evidence.

In the work on learning organisation of Argiris and Schön (1974) an interesting distinction between single loop learning and double loop learning is made. The single loop learning represents operationalization of goals, values, policies and following them by evaluating the current deviations from the desired state. In double loop learning the goals, values and policies might be amended according to changes that occur in meantime. Therefore, double loop learning model seems to be more empirical and practical way of learning because the environment might change dramatically in some cases affecting also the goals setting, the strategic fist action itself.

HEIs as Learning Organisation

Theoretical models of learning organisations are developed mainly focusing on the fields of business and industry. Observing the organisation of HEIs this paper tries to analyse the possibilities of developing the learning organisation in the context of HE.

Tackling the similar problem, Portfelt (2006) argues that there are two crucial characteristics that differentiate university organisations from other organisations (referencing to Baldridge and Birnbaum). First of all, public universities are not profit-oriented organisations. Since 1990s there have been considerable changes in funding schemes of public HE sector in many countries which created new economic environment. The ideas of new public management and entrepreneurial university could be seen as a response to this new economic environment, where the universities are forced to borrow strategies and methods from the business life. Notwithstanding, profit is not the primary goal of a university. The second specificity of university is its mission diffusion. Universities have to meet the needs of various internal and external stakeholders. This leads to diversification and specialisation of universities, making their missions diffused and sometimes conflicted. Therefore, unlike profit-making organisations, universities cannot quantify and measure their performance in relation to their mission, as precisely as for-profit organisations can. (Portfelt, 2006) Analysing this issue, Birnbaum argues that comparing HE and business organisation, there is no metric and goals in HE which are equivalent to money and profit in business. (Birnbaum, 1988, p.11)

The above described characteristics help us to understand the context of university in which we analyse the concept of learning organisation. There are several other aspects of university life that need to be considered, which can be seen as main impediments for development of learning organisation. Kofman and Senge (1993) identify three main factors which also form the basis of learning disabilities in society as a whole: fragmentation, competition and reactiveness. These “cultural dysfunctions” are directly imported from larger society into every organisation (including HEI) and define the way the organisations operate. (Kofman and Senge, 1993, p.7)

Fragmentation, authors explain, refers to analytical approach to solve problems. This involves breaking a problem into components, studying each component in isolation, and then synthesizing the components back into a whole. Thus, we eventually become convinced that knowledge is accumulated bits of information. According to the authors, this sort of linear thinking is becoming increasingly ineffective to address modern problems. In business, they describe the fragmentation as placing walls that separate different functions (or units) into independent entities.

Analysing the HEI as organisation, fragmentation can be recognized as the lack of communication on two levels: horizontal and vertical. Horizontal fragmentation is visible between different departments, faculties and units, while vertical refers to division between managerial, academic and administrative personnel.

Competition is overemphasized in modern society and, as authors claim, there is no healthy balance between competition and cooperation. Overemphasis on competition makes looking good more important than being good. The resulting fear of not looking good is one of the greatest enemies of learning. To learn, we need to acknowledge that there is something we don't know. But in business ignorance is seen as weakness. In response, people have developed defenses like working out problems in isolation, always displaying the best face in public, and never acknowledging the lack of information or skill. Overemphasis on competition also reinforces the orientation on short-term measurable results. So there is a lack of discipline needed for steady practice and deeper learning. This quick-fix thinking also blurs the big picture leading to “system blindness”. (Kofman & Senge, 1993, p. 9)

In HE sector the competition is seen within universities (between academics, between departments or units) as well as between them for scarce resources (personnel, finances or prestige). Quasi-market stimulates the competitiveness in the higher education sector. Unlike “real” market where the main criteria for performance evaluation is demand pull from customers, on quasi-market performance is evaluated by peers. (De Boer et al, 2007)

Reactiveness is the third “cultural dysfunction”, as Kofman and Senge defined it. Reactiveness refers to change only as reaction to outside forces. It is a fixation on problem-solving, rather than creation and innovation. People have become accustomed to conditioning by an external authority which leads to another problem – many organisations exercise authority in a way that undermines the intrinsic drive to learn. Many managers are problem-solving oriented and believe that people are willing to change only in times of crisis. Authors argue that there is a necessity to introduce creative rather than reactive learning in organisations.

University as an organisation is a complex system which is in a permanent and dynamic interaction with its environment. It adapts and changes in order to survive and thrive. According to their nature, these changes can be planned or “top-down”, and emergent or “bottom-up” (Halasz, 2010, p.52). The driver of changes can be internal or external. Top-down changes are deliberate and planned (e.g. externally driven generated by government regulation changes) while bottom-up are more spontaneous and emerging (e.g. changes generated by basic-level initiatives, such as department) (Halasz, 2010). The majority of day-to-day activities in university are emergent and internally driven. (Pausits, 2013) This means that the university, as an organisation, also has this “cultural dysfunction” being more reactive and oriented toward solving problems than toward creative learning.

Taking into consideration previous arguments saying that university has all three cultural dysfunctions, as Kofman and Senge defined it, the logical question is: Can university become a learning organisation? We believe it can.

Built on the idea of education (and research), with teaching and learning in its basis, the university as an organisation is a fertile ground for developing into a learning organisation. In a way, the roots of the learning organisation, as a theory, trace back to university, namely academic disciplines such as psychology, pedagogy and sociology, and their theories on learning (individual, group and team learning).

Universities throughout the world have been challenged in various ways in last three decades. Massification, emergence of new teaching and learning methods, change in funding schemes, increased cooperation, but at the same time the competition between universities – all these challenges fundamentally change HE sector. Universities have to adapt to this complex environment, and constantly rethink their position in society in order to become more agile and efficient. New environment requires new, innovative approaches to higher education, such as entrepreneurial university and university lifelong learning. Developing university, as an organisation, into a learning organisation seems a promising perspective, which can improve necessary flexibility and adaptability to cope with emergent situation.

Embracing the initial conceptualisation of the learning organisation by Senge (1994), HEIs should tackle the five disciplines essential to a learning organisation – systems thinking, personal mastery, mental models, shared vision and team learning. Related to HE context Senge’s five disciplines could be ‘translated’ in following manner:

Personal mastery is closely related to the concept of lifelong learning and continuous professional training. It implies that progress and growth of an organisation depend on personal and professional growth of its members.

Mental models, as a concept, are close to Clark’s concept of academic belief. (Clark, 1983) Deeply ingrained assumptions and generalizations (or beliefs) about the societal function of the university steer our understanding of higher education and influence our actions.

Building shared vision of the university goals is perhaps the most challenging milestone in developing learning organisation. Often, universities are complex systems with various departments and academic disciplines resulting in mission diffusion. Many universities tend to specialize thus gaining the competitive edge.

Team learning (between university personnel) and a culture of dialogue enables functioning of many research teams. This way of learning encourages cooperation within and between universities. However, the full potential of team learning remains often untapped in the university organisation due to abovementioned fragmentation.

Finally, the crucial, fifth discipline in Senge’s theory is systems thinking. Observing the university as a whole and overcoming the fragmentation is essential in order to develop previous four disciplines to their full potential.

When talking about organisation, Senge actually talks about people. His vision of a learning organisation is strongly people-oriented and focuses on organisational growth through personal growth. Therefore, the main generator for developing university learning organisation should be HR unit. Embracing the idea that we are all learners, Human Resource Management (HRM) should facilitate the learning of university personnel towards achieving the five disciplines on a personal and consequently on an organisational level.

Creating a bridge between administrative and academic personnel, the position of HR unit provides an opportunity for overcoming the three main impediments for developing learning organisation: fragmentation, competition and reactiveness (defined by Kofman and Senge). Enhancing communication within university cutting across vertical and horizontal lines thus creating new communication channels could decrease the fragmentation. The balance between competition and cooperation within university could be reinforced by specifying in details the profiles and competences of various categories of personnel harmonising their activities and facilitating teamwork. Planning of human resources and human resource development (HRD) would be the two main areas of activities which could lead beyond reactiveness toward strategic thinking.

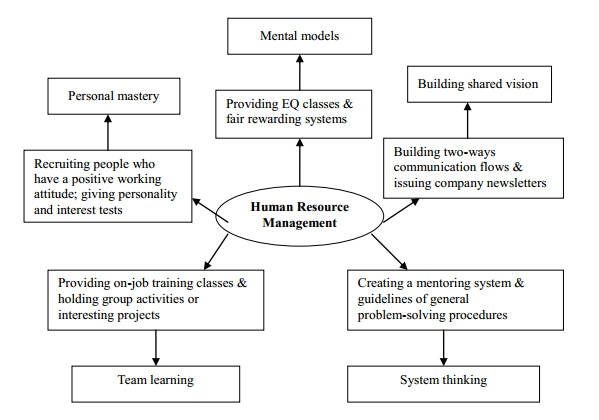

The full potential of a learning culture within university organisation can be reached only through people learning together. The incubator of this process is HR unit with well-established HRM and HRD. Analysing business organisations Yu Wang (2006) suggests specific strategies that can be adopted by HRM regarding Senge’s five disciplines (see the Figure 1).

Figure 1: HRM Strategies in the Learning Organisation (Source: Yu Wang, 2006, p.55)

As we can see in the Figure 1, author is mainly focusing on the development of learning organisation from the perspective of company. Nevertheless, he gives us a good framework for developing specific HR tools that can be considered for developing Senge’s five disciplines in HEIs, such as:

- HR planning with emphasis to recruiting of candidates with willingness to learn;

- Training system targeting establishment and broadening of learning capacities of individuals, teams and, consequently the whole institution;

- Integrated HR information system serving as a platform for planning, controlling, coordinating and evaluating activities;

- Sharing information about HEI’s performance and challenges on regular basis;

- Remuneration oriented towards learning objectives.

Conclusion

The idea of learning organisation in the context of university is not completely new. As we elaborated earlier, similar issues regarding functioning of the university have been explored before. Still, the perspective of learning organisation provides a slightly different (managerial) framework for rethinking the organisational issues in HEIs. What we see as the main contribution of this concept to HEIs is the emphasis on professional development through learning with others. HRM plays the essential role in supporting the culture of learning by seeding it throughout the organisation.

Although still underdeveloped in European universities, HRM has a great potential in strategy development of the university by translating it into a strategy for the personnel. (Böckelmann et al., 2010) Strategic orientation of a university towards developing a learning organisation can be successful if realised within HRM. In addition, the list of suggested HRM tools can be further developed and expanded by future studies.

References

Argote, L. (2013), Organizational Learning: Creating, Retaining and Transferring Knowledge. 2nd ed. New York: Springer.

Argyris, C. and Schön, D. (1974), Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Birnbaum, R. (1988), How Colleges Work, The Cybernetics of Academic Organization and Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Böckelmann, Ch., Reif, L. and Fröhlich, M. (2010), ‘Human Resources Management’, in J. Huisman and A. Pausits (Eds.), Higher Education Management and Development – Compendium for Managers, Münster; New York; München; Berlin: Waxmann, pp. 159-175.

Clark, R. B. (1983), The higher education system: academic organization in cross-national perspective, Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Coopey, J. (1995), The Learning Organization, Power, Politics and Ideology Introduction. Management Learning, 26(2) 193-213.

De Boer, H., Enders, J. and Schimank, U. (2007), On the Way Towards New Public Management? The Governance of University Systems in England, the Netherlands, Austria, and Germany. In: Jansen, D. (ed.). New Forms of Governance in Research Organizations. Disciplinary Approaches, Interfaces and Integration. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 135-152.

De Boer, H., Jongbloed, B., Enders, J. and File, J. (2008), Progress in higher education reform across Europe. Funding Reform, Volume 1: Executive Summary and main report. CHEPS: Enschede.

Halasz, G. (2010), ‘Organisational Change and Development in Higher Education’, in J. Huisman and A. Pausits (Eds.), Higher Education Management and Development – Compendium for Managers, Münster; New York; München; Berlin: Waxmann, pp. 51-63.

Iandoli, L. and Zollo, G. (2008), Organizational Cognition and Learning: Building Systems for the Learning Organisation. London: Information Science Publishing.

Kofman, F. and Senge, P. M. (1993), Communities of Comment: The Heart of Learning Organizations, http://www.ebacs.net/pdf/building/4.pdf (05.01.2014).

Pausits, A. (2013), HRM – From here to there, (study material).

Portfelt, I. S. (2006), The University; A Learning Organization? – An Illuminative Review Based on System Theory, Karlstad University Studies, http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:6505/FULLTEXT01.pdf (04.01.2014).

Senge, P. (1994), The Fifth Discipline - The Art and Practice of the Learning Organisation, New York: Doubleday.

Schön, D. (1973), Beyond the Stable State. New York: Penguin.

Yu Wang, P. (2006), Human Resource Management Plays a New Role in Learning Organizations. The Journal of Human Resource and Adult Learning, 2 (2) 52-56.