Master Thesis Reader - Research and Innovation in Higher Education

Institutional Autonomy in Argentinean Public universities: The case of NUC

Acuna Lopez

Background

The tension that exists between a university’s autonomy and its responsibility to the public constitutes a persistent theme in public higher education in Argentina. Despite the fact that academic freedom has been widely defined, the concept of institutional autonomy has been less clear. Ideas of institutional autonomy, however, create the environment within which public policy decisions arise. In Argentina public universities are funded almost entirely by the state. In today's changing environment, as public resources continue to decrease, the state, being the main stakeholder, has started to demand for accountability. Although the literature addresses these conditions, less is known about how the state’s influence shapes institutional autonomy.

In Argentina, the relationship between the state and the university has always been complex and problematic, and it has historically known very few moments of harmony (Griffouliere, 2008). In her book The University in the XXI Century (1995), de Sousa Santos described three crises that universities were undergoing: crisis of hegemony, crisis of legitimacy and institutional crisis. Since then, that diagnosis has become an essential element in understanding the problems universities face. From these three it was the institutional crisis that struck deep in Argentinean public universities, result of neoliberal policies that the state underwent (Mazzola, 2008).

As a result of this crisis, the institutional autonomy held as sacred by public universities underwent considerable change. The traditional passive attitude of the State towards the universities began to change rapidly towards governmental activism in a context of crisis and budget deficit. A lot of government initiatives based on the evaluation and differentiation began to change old patterns of relations between the state and universities (Serrano García & Gonzalez Villanueva 2012).

It is clear then that university autonomy is a shifting notion that has experienced re- interpretations and reformulations over time. It is conceded that total independence from government cannot be achieved, particularly so in higher education systems where universities rely on funding by the state. Accordingly, as Löscher & Dannemann express it “there is not university autonomy as such, but there are degrees of autonomy that depend on the relation between co-existing different forms of interests at a given point in time. Thus, an idea of university autonomy is challenged by the versions of university autonomy that can be achieved in reality” (Löscher & Dannemann, 2004 p.7).

Surprisingly, the issue of autonomy in the Argentinean HE system has not been studied well. The studies that exist have focused on the historical development of autonomy but no studies have been carried out to study the degree of real autonomy that universities have when contrasted to the legal standing of autonomy. Consequently, this study attempts to shed some light on the status of autonomy in Argentinean public universities. However, to make the study more feasible, only one public university, NUC, will be analyzed and taken as a point of reference.

Then, the central research questions of this thesis are:

What is the real degree of autonomy that public universities in Argentina have? Does the autonomy reflected in the laws corresponds with the real autonomy universities have or is there a gap between legal autonomy and real autonomy?

In order to answer these questions, some sub-research questions need to be answered:

- What is the relationship between the state and public universities in Argentina?

- What is the effect this relationship has on institutional autonomy?

Analytical Framework

The research problems were addressed by applying an analytical conceptual framework based on resource dependency theory (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). In addition to this, Estermann & Nokkala, (2009) dimensions of autonomy were used to explore the autonomy of universities. In order to do this the third and last part of this framework focused on institutional autonomy in Argentina from a legal perspective. Through these three perspectives, the emphasis of this study was on understanding and interpreting the complex interaction between the state as main provider and public universities, and by analyzing the different dimensions of autonomy it attempted to determine the real degree of autonomy they enjoy.

Resource Dependency Theory (RDT)

RDT is a well-known theory in the social sciences that helps us to understand organization- environment relations. Its main purpose is to show how organizations act strategically and make choices to manage their dependency to the parts of their environment that control important resources (Leisyte, 2007). The basic argument of resource dependence theory can be summarized as follows:

- Organizations depend on resources.

- These resources ultimately originate from an organization's environment.

- The environment, to a considerable extent, contains other organizations.

- The resources one organization needs are thus often in the hand of other organizations.

- Resources are a basis of power.

- Legally independent organizations can therefore depend on each other. (Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. 1978)

RDT characterizes the links among organizations as a set of power relations based on exchange resources. It proposes that actors lacking in essential resources will seek to establish relationships with (i.e., be dependent upon) others in order to obtain needed resources. Also, organizations endeavor to change their dependence relationships by either minimizing their own dependence or by increasing the dependence of other organizations on them. Attaining either objective is thought to affect the exchange between organizations, thereby affecting an organization’s power. Thus, organizations are seen as coalitions modifying their structure and patterns of behavior to acquire and maintain needed external resources (Davis and Cobb, 2010).

In analyzing the relationship between resources and the autonomy of universities, it can be argued that because one party is dependent on the other for the supply of resources or services, this means that such party is subordinated to the other. Likewise, Pfeffer and Salancik (1978) sustain that the party who provides resources to an organization has the capability of exerting power over it. Thus, it becomes clear that the analysis of the interaction between organizations and their environments is inextricably related to their autonomy, as this relationship has the capability of deeply affecting it. In the words of Pfeffer and Salancik, (1978, p. 257) “organizations are involved in a constant struggle for autonomy, as they areconfronted with constraint and external control”.

Dimensions of Autonomy

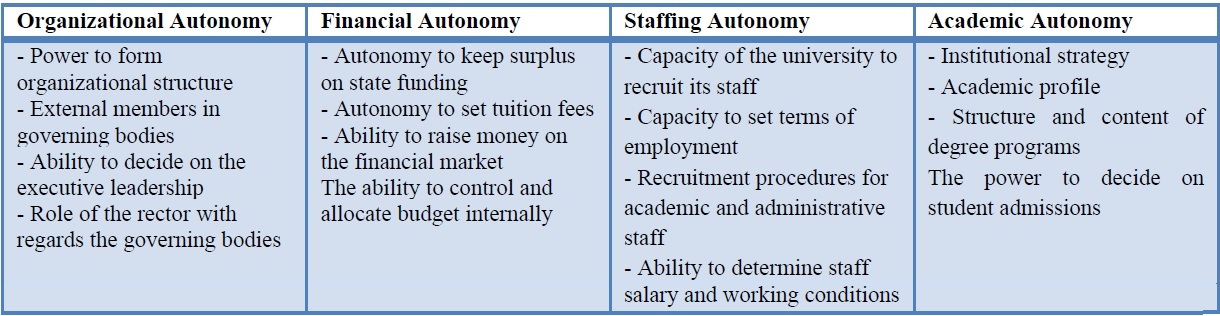

For the purpose of this work the dimensions of institutional autonomy made by Estermann & Nokkala (2009) will be described in detail. These dimensions will serve as the framework to analyze institutional autonomy in Argentinean public universities through the case of the NUC. According to Estermann & Nokkala, (2009:40) the basic dimensions of institutional autonomy in HEIs are organizational, financial, staffing and academic autonomy.

Organizational autonomy

Organizational autonomy refers to the ability universities have to decide freely on their internal organization, such as the election of executive leadership, the composition of decision-making bodies, the formation of internal academic structures and the decision of who is accountable to whom within the university. That is to say, it focuses on the universities’ capacity to define the modalities of its leadership model (Camaño Cano, 2010). However, whilst most of the time the academic and administrative structures are under university control, the state often shapes the governance structure and leadership of universities. Furthermore, another significant element related to how governing bodies are structured concerns whether they include external members and how these members are selected. The matter of concern here is whether the selection is implemented by the universities themselves and/or by an external body or authority (Estermann & Nokkala, 2009). Another important indicator of a university’s organizational autonomy is its capacity to decide on their executive leadership. More often than not the composition and competencies of these people are specified by law and not by the universities themselves. (Estermann, Nokkala & Steinel, 2011).

Financial autonomy

Another characteristic of institutional autonomy, which adds complexity and significance to the matter, is the scope of financial autonomy that universities have (Kohtamaki, 2009). This is so because it is a crucial factor in allowing HEIs to achieve strategic goals. Financial autonomy is the ability HEIs have to handle their financial affairs without outside influence. The ability to administer funds independently permits institutions to set and accomplish strategic goals. If we consider this matter from the government university relationship perspective, financial autonomy refers to the freedom of the institution to decide over its financial issues without government’s interference. Estermann and Nokkala (2009:18) describe financial autonomy by referring to the following issues:

1. The extent to which they accumulate reserves and keep surplus on state funding 2. The ability of universities to set tuition fees, 3. Their ability to borrow money on the financial markets 4. Their ability to invest in financial products 5. Their ability to issue shares and bonds 6. Their ability to own the land and buildings they occupy. Another important element of financial autonomy is universities’ capacity to fully control and allocate their budget within the institution. Furthermore, the manner or method in which funding is allocated also constitutes an important factor as it reflects to what degree universities are independent from the influence of political authorities.

Staffing autonomy

Staffing autonomy refers to the capacity universities have to recruit their own staff and negotiate their terms of employment (Estermann & Nokkala, 2009). However, the ability of universities to decide on these matters is inherently associated to their financial and academic autonomy. This is so because staff wages as well as their employment contracts are determined by financial agreements between the university and its funders and also by the fact that financial regulations on staffing have an impact on the ability to recruit the appropriate staff (Tremblay, et al., 2008). It is therefore necessary to analyze this dimension of autonomy in connection to the institution’s academic and financial autonomy. Furthermore, the status of university employees, whether they are civil servants or not, the recruitment procedures followed for the appointment of senior academic staff and the salary levels also serve as indicators to analyze staffing autonomy. (Estermann & Nokkala, 2009:40).

Academic autonomy

Academic autonomy indicates universities’ ability to determine their institutional strategy, to define their basic mission as regards their teaching and research, including all the decisions concerning the actions that are necessary to best achieve these missions (Estermann & Nokkala, 2009). It is important to highlight, that a university’s ability to define its institutional strategy is not only inherent of its academic autonomy but it also involves significant elements of the other dimensions. Academic autonomy may therefore be considered as a framework for all the main activities of the university.

Other important elements of academic autonomy are the power universities have to define their academic profile, the ability to introduce or terminate degree programs and the power to decide on the structure and content of these programs. In addition to all the forgoing, the responsibilities of universities with respects to the quality control of programs and degrees, and the extent to which they can decide on student admissions are also the significant elements of academic autonomy of universities (Estermann & Nokkala, 2009).

These dimensions of autonomy (Eastermann & Nokkala, 2009) specified the kind of actions that should be possible for autonomous HEIs. However, they are not enough to analyze the degree of autonomy that public universities in Argentina really have. In order to do this, a clear perception of the legal framework that determines the autonomy of such institutions in Argentina is essential.

Table 1: List of Indicators for analysis of each dimension of Autonomy.

University Autonomy in Argentina, legal perspective

In Argentina, university autonomy is the legal and political foundation on which the relationship between the National Government and public universities is established. For the purpose of this research, university autonomy will only be considered from a legal perspective as this perspective. The importance of institutional autonomy in public universities in Argentina is clearly demonstrated by the fact that it is ensured in the national constitution. The Argentinean Constitution states in article 75 paragraph19 that it corresponds to the Congress:

“...to ensure the principles of free and equitable public education and the autonomy and autarky of national universities.” (National Constitution). The sanction of the National Higher Education Law (HEL) of 1995 (Law No 24.521/1995) clearly states the autonomy Argentinean public universities are to enjoy.

In accordance to the research questions and analytical framework proposed for this research and in order to make it coherent and cohesive, only those articles of the LES that refer to the four dimensions of autonomy proposed by Estermann and Nokkala (2009) will be presented.

The Argentinean LES, in its 29th article states that Universities will have academic and institutional autonomy, which comprises the following attributes:

- To enact and amend their statute;

- To Define their governing bodies, to establish their functions, decide on their integration and choose their authorities in accordance with what is established by their statutes and required by this Act;

- To conduct their affair without the interference of political interests.

- Manage their assets and resources, according to their statutes and laws governing the matter;

- Create undergraduate and graduate programs;

- Formulate and develop their curricula, scientific research, outreach and community services including the teaching of professional ethics;

- To grant academic degrees and authorization certificates;

- Provide education for experimentation, innovative teaching or teaching practice in preuniversity;

- To establish the system of access, retention and promotion of teaching and non-teaching staff;

- Appoint and dismiss staff;

- Establish the system of admission, retention and promotion of students, as well as the system of equivalences;

Other significant articles of the HEL as regards autonomy are article 51, which determines that the admission to the university academic career will be made by public and open competitions and that teachers appointed by competition must be a percentage not less than seventy percent (70%) of the respective plants of each university institution and article 52 which refers to the organizational structure of universities by stating that the statutes of national universities shall provide their organs of government, both collegiate and unitary, as well as its composition and powers. Article 53 of the HEL is also important for its implications on institutional autonomy as it determines that the collegiate governing bodies will be composed according to what is determined by the statutes of each university; but, the statutes must ensure that the teaching faculty has the highest relative representation, which shall not be less than fifty percent (50%) of all its members; That the representatives of the students are regular students and have completed at least thirty percent (30%) of all subjects enrolled in the career; that the non-teaching staff have representation in these bodies to the extent determined by each institution; and that graduates, should be incorporated into the collegiate bodies. Article 55 establishes that the statutes shall provide for the constitution of Social Council, in which the different sectors and interests of the local community will be represented, with the mission to cooperate with the university institution in its articulation with the environment in which it is inserted. As regards sustainability and the economicfinancial regime the law states in article 58 that the national State must ensure financial support for the maintenance of national universities, to ensure normal operation, development and fulfillment of its purposes. And that for the distribution of this contribution to the national universities in the country indicators of efficiency and equity shall be taken into account. Article 59 determines that national universities shall have economic and financial autarky, which shall be exercised within the regime of the law 24.156 of Financial Management of the National Public Sector. It also introduces that in this context it corresponds to the institutions: To manage their assets and approve their budget, remarking that resources unutilized at the end of each year are automatically transferred to the next; set the salary regime of academic and managerial personnel; make rules relating to the generation of additional contributions than those from the National Treasury, through loans, the sale of bonds, goods, products, rights or services, grants, contributions, bequests, fees or charges for services that provide resources. This article also dictates that the additional resources that may arise from contributions or fees, must be primarily intended to scholarships loans, grants or credits or other student aid and didactic support for undergraduate students and that they may not be used to finance current expenditure.

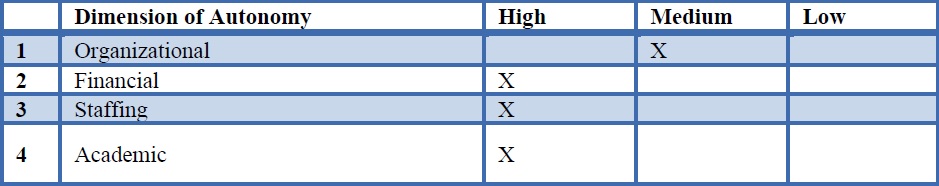

Through the careful study of the legislation it can be concluded that the institutional autonomy of universities in Argentina should be quite high. If we consider the regulations with respect to Estermann and Nokkala’s dimensions, it can be inferred that-from a legal perspective-the financial, staffing and academic autonomy of universities is quite high, while organizational autonomy is at a medium level as illustrated in table 2.

Table 2: Status of institutional autonomy in Argentina according to the HEL.

Methodology

In order to conduct this research, qualitative research methods were used for data collection and analysis. Qualitative research methods were preferred over quantitative research methods based on the fact that for data analysis the research depended on the perceptions, experiences and opinions of participants. By using qualitative research methods the researcher seeks “an understanding of behavior, values, beliefs, and so on in terms of the context in which the research is conducted.” (Bryman, 2008, p. 394) it also enables the researcher to gain a more detailed understanding of the phenomena of interest than with quantitative research (Yin, 2010). Furthermore, qualitative research methods are also effective in explaining unusual situations that might not be identified by utilizing quantitative methods.

Within qualitative research methods, a case study methodology was employed because of its convenience in showing the existing situations in the area under study. This approach was chosen because a case study is an in-depth examination of a single instance of particular phenomena (Yin, 2010) and for this reason it is appropriate to examine a particular program, event, project or institution in detail (Merriam, 1988). One of the most significant issues in designing case studies is the designation of the unit of analysis and then confirming that this unit is compatible with the research objectives of the study (Gray, 2004:128). Another important consideration in choosing this method was the fact that case studies, unlike other research designs, do not rely on an individual method of data collection or data analysis. For this reason, it is possible to use any method of gathering data in a case study (Merriam, 1988). This means that there can be various sources of evidence for this type of study such as various documents, archival records, interviews, field observations, participant observation etc., (Yin, 2010; Merriam, 1988).

Consequently, to validate the case study this study mainly relied on document analysis and semistructured interviews. The selection of this methodology was significant to this study as it was instrumental in answering the research questions. Besides, this method was important to clearly depict the status of autonomy in higher education in Argentina in general and in NUC in particular so as to come up with important findings.

Sampling

The selection of participants in qualitative research is based on their characteristics and knowledge as they relate to the research questions being investigated (Lodico, Spaulding, & Voegtle, 2010). Based on this premise, two types of sampling were employed in this study, purposeful and snowball sampling. Purposeful sampling is done when information is gathered from all those people who are in the best position to provide the required information. According to Patton (1990) cited in Lodico et al. (2010), “The logic and power of purposeful sampling lies in selecting information-rich cases for study in depth. Information-rich cases are those from which one can learn a great deal about issues of central importance to the purpose of the research”. The aim of this type of sample is to have those participants that will yield the most relevant and plentiful data, given the topic of study (Yin, 2010).

For the purpose of this study, the sample required participants from two groups: academics and administrators. For this reason the rector of the university and the deans of three faculties were selected. These people are essential as they have a dual function within NUC being academics and administrators. From the pool of academics two professors from two of the faculties were chosen and in administration the director of finance was selected. From this initial selection further participants were added through snowball sampling, as the first interviewees suggested more participants based on their knowledge of the topic. Researchers inform that sometimes snowball sampling, which is asking an informant to suggest another informant, follows purposive sampling (Yin, 2010; Gray, 2009). From the people suggested only four of them were selected for interviewing because, as Yin (2010:89) states, “selecting new data collection units as an offshoot of existing ones—can be acceptable if the snowballing is purposeful, not done out of convenience.” A total of twelve interviews were done for this study, the rector of the university, three deans, one head of department, three professors and from administration: the head of finance, the head of human resources, the secretary of science and technology and the academic secretary.

Data gathering methods In order to obtain adequate information that helps to answer the research questions, a thorough documents analysis was made. This document analysis helped the researcher to compare what was said in the interview and done in practice with what was expressed in the laws both at the national level and institutional level. First, at the national level the Constitution of Argentina 1994 was analyzed only in the sections related to HE. Second, a deep analysis was made on the HE law (Law No. 24.521/1995), the financial administration law (Law No. 24.156/1992) and the educational financing law (Law No. 26.075/2005) to study their impact on university autonomy. Third, the old HE laws were explored as well, in order to investigate their significance in shaping the autonomy universities enjoy today. At the institutional level the strategy of the university as well as its statute were thoroughly studied. The second data gathering method used was semi-structured interviews, “semi-structured interview allows for probing of views and opinions where it is desirable for respondents to expand on their answers. Such probing may also allow for the diversion of the interview into new pathways that, while not originally considered as part of the interview, help towards meeting the research objectives” (Gray, 2009:217). The interviews were essential in filling the gap created by the document analysis. Besides, it was found that important piece of information from the experience of the interviewees that was not in the mind of the researcher helped much in the interpretation of the data.

Key Findings

The information provided by the interviewees together with the document analysis conducted helped determine the state of autonomy in Argentinean public universities in the four dimensions as presented by Estermann and Nokkala.

Organizational Autonomy at NUC

According to Estermann and Nokkala (2009), there is a strong connection between a university’s governance structure and the organizational autonomy it has. Various authors highlight that high organizational autonomy is essential for HEIs to be effective and efficient. In NUC, the level of organizational autonomy can be said to be medium. It is influenced by national frameworks as the HEL provides the basic structure, but the university still retains a certain degree of autonomy in the organization of its governing bodies. As regards the leadership, in NUC the rector is an academic “primus inter pares”, selected by the internal academic community among the professors of the university, chair of the university’s assembly, with term and qualifications determined in the law. The same can be said of the Deans and Department heads.

In spite of the fact that the law determines their qualifications, it is the university that determines the power, duties and responsibilities of its authorities, not the state. In general, the main restrictions of organizational autonomy of NUC are, besides from the regulations introduced by the HEL, related to the composition of the governing bodies: the fact that there are no external members in the governing bodies and the influence of political interests in the government on the university. As regards the presence of external members, Estermann and Nokkala (2009) state that their inclusion forms an important part of more autonomous universities’ accountability towards their stakeholders and society at large. So, this will form a crucial part of future reforms on governance, as there is “a pressing need to find the right degree of accountability by integrating external stakeholders in an efficient and appropriate way, in the light of the mission and the strategic priorities of each and every university.” (Estermann and Nokkala, 2009:17)

As regards the distance between what happens in the university and what the law states, it can be mentioned that, in general the laws as regards this dimension of autonomy are followed, with some exceptions. Two aspects of the law in particular are not respected, first, the one that says that political interests shall not intervene in the workings of the university and secondly, the one that establishes that external members should be included in the governing bodies. Both of which collaborate to limit the organizational autonomy of NUC and might have a negative effect on the opportunity of the university to compete effectively and efficiently in the globalized world in general and with the national universities in particular.

Financial Autonomy at NUC

Financial autonomy of public universities is a crucial factor for them to achieve their strategic goals. Additionally it is clear that this is the dimension of autonomy that has the greatest influence on the others as, if there is no autonomy for universities to act freely in their financial issues, it is highly unlikely that the other dimensions of autonomy will function effectively.

The analysis of this dimension of autonomy indicates that, in opposition to what is stated in the laws, the financial autonomy of NUC is quite low. Despite the fact that the HEL, grants financial autarky, universities do not get the totality of their annual budget in block grant form. Carlos Greco (2009:9) explains the fact that the State grants project funds separately instead of incorporating it to the recurrent budget by saying “ ... the State has discovered that financial incentives are a more effective method to influence in the functioning of universities than the pure administrative intervention that was used in other times...”. Therefore, the government uses this grant to indirectly steer the universities in the direction they want and grants project funds in areas they consider a priority, which may not coincide with the priorities of the universities.

In this dimension, the distance between what the law states and what is done in practice is quite noticeable. For instance, both the HEL and NUC’s internal statute indicate that the university has the autonomy to keep the surplus from all the funds received by the state. However, this is only partially applied, as the income from projects has to be returned if it is not used. With respect to the topic of tuition fees, the National constitution declares that all public education should be free of charge; however, universities charge fees for graduate, postgraduate and distance programs. As regards the internal allocation of funds, the HEL states that universities shall be completely free to manage the funds received from the state; nonetheless, this is not fully applied in practice as the budget assigned for salaries a for projects cannot be shifted to other expenses. All in all, it can be said the financial autonomy is quite limited.

Staffing Autonomy at NUC

Staffing autonomy refers to the ability universities should have to recruit their staff and manage their working conditions without outside interference. The basic idea behind institutional autonomy is that HEIs operate better if they are in control of their business (Fielden, 2008). Estermann and Nokkala (2009) described that the ability of universities to decide on staff recruitment is closely related with the degree of autonomy they have on financial and academic matters. It is especially significant to notice that one of the important elements of staffing autonomy is the extent to which universities have control over the financial aspects related to their staff (Eastermann & Nokkala, 2009).

As it was indicated above, NUC functions with little financial autonomy. In addition to this and closely connected, NUC is characterized by low staffing autonomy. It is true that, NUC is free to recruit its academic staff without interference from the state. But, the same cannot be said of the administrative staff. As their working conditions are decided by agreement between the government and the trade unions and it is the trade union that controls the recruitment process.

As regards the terms of employment, NUC sets the regulations and has decision power over academics but administrative personnel conditions have to be agreed upon with the trade union. This creates inequalities between the personnel and it interferes in the university plans to create a professional, well prepared administrative structure. Respecting the ability of universities to decide on salary levels, the law grants them the right but in reality they are decided at the national level. Furthermore, the bureaucratic nature of the governance model of NUC is clearly manifested in the recruitment procedure, as it takes long steps to recruit an individual teacher.

To conclude, the low staffing autonomy that NUC possesses is the result of the confluence of many forces. The inability of the university to determine the salary of the staff and to decide on the recruitment and working conditions of administrative staff, together with the bureaucratic nature of the university are the main indicators that can be given for limited staffing autonomy. It can also be added, that it is in this dimension of autonomy where the gap between the law and what happens in reality is more pronounced as none of the regulations related to this are applied. This is caused mostly by the limited financial autonomy NUC enjoys.

Academic Autonomy at NUC

The literature shows that academic autonomy is one of the most important dimensions-if not the most-of institutional autonomy. It mainly refers to institutions having autonomy to decide on their institutional strategy and academic profile, introduce and cease degree programs and decide on the admission of students. Essentially, the key issues of academic autonomy are the ability of universities to decide on their academic profiles like the areas they confer degrees in, and the ability to select students (Eastermann and Nokkala, 2009).

The analysis showed that the level of academic autonomy in NUC is not high as the law suggests but that it is at a medium level. It is interesting to note that NUC has the ability to open new degree programs. Nonetheless, despite the regulations, there seems to be a strong steering through funding by MOE, which has a definite influence in the ability of the university to do so. As regards the termination of programs there are no external restrictions though in some cases internal pressures may hinder universities’ ability to do this. This reflects that the academic autonomy of NUC is closely related to the financial autonomy of universities in Argentina. In other words, the unavailability of funds is a factor that contributes to the reduction of academic autonomy of the university.

As regards the mission and vision, the law provides the universities the autonomy to decide without interference. Notwithstanding, there seems to be some similarity with the other public universities, which suggests that universities are not as free as expected in this area and shows that the state has an influence on the educational strategies of the universities. Despite this interference by the state, eleven out of twelve of the respondents feel that the university does enjoy a high degree of academic autonomy.

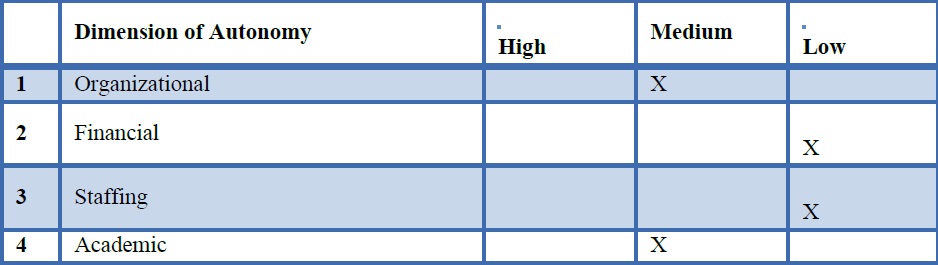

The real state of autonomy in NUC

The thorough analysis of the four dimensions of autonomy in NUC revealed that the institutional autonomy in Argentinean public universities is not as high as the HEL determines it and that indeed there exists a gap between what the laws express what happens in reality. The findings as regards the real status of autonomy in NUC are summarized in table 5.

Table 3: Real status of institutional autonomy in Argentina.

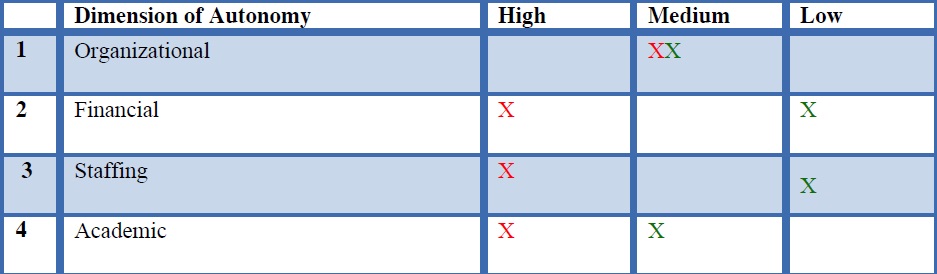

The results shown in this table, when compared to the autonomy expressed in the law (shown in table 2) reveal that there is a big discrepancy between what is stated in the laws and what is actually happening in NUC. From the four dimensions, the only one that remained in the same position was organizational autonomy, which, in both cases, is at a medium position. In this case, although the law is not applied to the fullest extent, as previously expressed, all of the interviewees considered that the university still had a certain degree of autonomy. As regards academic autonomy, based on what the HEL states, universities should have a high degree of autonomy, but this is not shown in reality. Ten out of twelve of the interviewees agreed that the actual level of academic autonomy is medium, as, in spite of the existence of certain limitations, NUC is still autonomous in these regards.

The dimensions of autonomy where the gap is particularly significant are the financial and staffing dimensions. The HEL provides that in these matters UNCA should be very autonomous when in reality the opposite happens. In these two dimensions according to what was expressed by the participants, the level of autonomy is low.

Table 4: Gap between autonomy expressed in law and real autonomy in UNCA

• LAW

• REAL

Having determined that this gap exists, it is important now to determine the reasons behind it. As proposed by resource dependence theory universities depend on their environment for essential resources and, in order to secure them, they are many times compelled to negotiate with the providers. If organizations cannot reduce their dependence to these providers by, for instance, diversifying their resources, their autonomy is affected. In the case of Argentina, where most of the public universities depend almost exclusively on state funds for their survival, their power of negotiation is very low and, therefore, their dependence is very high and, consequently, their autonomy is reduced (Leisyte, 2007).

Reasons for the gap between legal and real In accordance to the responses provided by the interviewees, the discrepancies that exist between law and practice in public universities can be attributed to, on the one hand to economic concerns and on the other to political implications.

Nine out of ten of the interviewees stated that economic situation Argentina is undergoing directly affects the autonomy of universities. As the representative from the financial office stated: ...the current economic situation creates a lot of uncertainty and distrust. This is why, even if we can supplement our funding through loans or by investing in the financial market, we do not do it. It would be too risky (Administrator 1).

Furthermore, the severe lack of funds that the Argentinean public university system has caused universities to be unable to fulfill many of the activities that by law they are entitled to and that are essential to their autonomy. For instance, seven of the respondents affirmed that the lack of sufficient funds prevents universities from being able to determine the salary levels of their staff and has a direct impact in the creation or not of new programs. Despite the fact the HEL determines that universities are free to determine their salary levels, their budgetary constraints force university authorities to adopt the salary scales dictated at the national level. This hinders the possibility of universities to attract highly qualified personnel. As regards the creation of new courses, in spite of the fact that universities are permitted to decide on this, new programs are introduced only if the state provides the needed funds, so in the end it is the state that decides which programs are opened and which ones are not. These are only two examples of how the scarcity of resources left universities unable to resist the interference of the state in their affairs and consequently loose their autonomy.

This can be seen, for example, in the distribution of state funds among public universities. These are supposed to come from negotiations between the universities and the state where indicators of “efficiency and equity” are used to calculate the funds each university is going to receive. However, this is not the case as those universities, which have strong ties with the government, are given much more funds than they actually need and those, which are not, are underfunded. This leaves these universities in a position where they cannot oppose the interference of the government in their affairs. Only the very few universities, which have been able to diversify their sources of income in order to avoid their dependence on state funds, can do this. However, due to the economic situation in the country, this is impossible for most universities.

Recommendations

Based on the findings and the conclusion drawn from this study, it is important to provide practical recommendations that will help in understanding and solving the existent problems of NUC and other public universities in Argentina.

All in all, it can be said that in order for NUC and the rest of Argentinean universities to reach their full potential and become true centers of excellence in the internal and external markets, the gap that exists between formal and real autonomy needs to be closed, or at least reduced. In order to achieve this, several changes need to be introduced. First of all, it would be important to reevaluate and reformulate the HEL to avoid ambiguities and provide regulations that will be followed. In the last decade, there have been several attempts to draft projects of law, but they have not been accomplished. Secondly, it is essential to reform the system for allocating and distributing money between the universities, introducing a system that is not based on negotiations or on vague indicators like “efficiency and equity”, but on objective criteria that would ensure the fair distribution of funds among universities. Thirdly, it is critical for universities to diversify their sources of income and to actively engage in establishing connections with the industry and service sectors. Only by doing this, will they reduce their dependence to the state and increase their responsiveness to their environment, becoming more autonomous but being accountable to their stakeholders.

Furthermore, it is extremely important for the policy makers to recognize that these changes would not generate the desired results unless they are fully communicated with the people who will implement them. Therefore, it is suggested that the MOE should establish a forum with HEIs to discuss what needs to be changed and to make suggestions that are clear to all and accepted by consensus. In order for the changes to be accepted, the university community should participate not only in the implementation but, most importantly, in the design so as to develop a sense of belonging for the type of change needed. Additionally, the executive leadership of the university should continuously inform and make the staff, students and graduates participate in any changes before starting to implement them. But, in other for change to be effective, it needs not only to provide from the state but the universities themselves.

Implications for further research

There is still a lot to be done to have a full understanding of the system. In this respect, this study would like to indicate multiple opportunities for further research. To start with, more comprehensive research at the system level- employing multiple of research methods- should be conducted to analyze deeply the dynamics of autonomy in public universities in Argentina. For instance, both quantitative and qualitative approaches could be used to obtain more substantial data. About the data gathering methods, apart from interviews, focus group discussions could be a helpful instrument to acquire more relevant information. In assessing the status autonomy and identifying the government-universities relationship, it is highly advisable to include the Ministry personnel or officials, as they would assist in providing a more complete picture on the issue in question. Furthermore, different stakeholders who are involved in the HE system should be involved to analyze it more comprehensively for example students and graduates.

References

Acosta Silva, Adrián. (2008), La autonomía universitaria en América Latina: Problemas, desafíos y temas capitales Universidades, Vol. LVIII, Núm. 36, pp. 69-82 Unión de Universidades de América Latina y el Caribe México.

Albornoz, O. (1991), Autonomy and accountability in higher education. Prospects, 21(2): 204-213.

Alcántara, A. (2009), La autonomía universitaria en las universidades públicas mexicanas: las vicisitudes de un concepto y una práctica institucional. La Universidad Pública en México, México, UNAM-Seminario de Educación Superior/Porrúa, 113-146.

Berdahl, Robert. (1990), Academic freedom, autonomy and accountability in British universities, Studies in Higher Education, 15(2): 169-180.

Bryman, A. (2008), Social research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Camaño Cano, V. M. (2010), La autonomía universitaria a Debate. una visión DesDe américa Latina. Revista de la educación superior, 39(156): 105-109.

Caplán, Ruth (2010), El financiamiento de la educación superior a través del presupuesto y la autonomía universitaria: Son compatibles en la actualidad? ICAP-Revista Centroamericana de Administración Pública, (58-59): 173-189.

De Boer, H., & File, J. (2009), Higher education governance reforms across Europe. CHEPS, The Netherlands. Retrieved online on 17 Dec 2013: Available at: http://www.utwente.nl/mb/cheps/publications/publications%202009/c9hdb101%20modern%20project%20report.pdf.

De Boer, H., Jongbloed, B., Enders, J., & File, J. (2010), Progress in higher education reform across Europe: Governance reform. Enschede: Center for Higher Education Policy Studies.

De la Rosa, A. R. (2007), Institutional autonomy and academic freedom: A perspective from the American continent. Higher Education Policy, 20(3): 275-288.

Delfino, J. A., & Gertel, H. R. (1996), Nuevas direcciones en el financiamiento de la educación superior: Modelos de asignación del aporte público. Ministerio de Cultura y Educación, Secretaría de Políticas Universitarias.

Estermann, T., & Nokkala, T. (2009), University autonomy in Europe I.Brussels: European University Association.

Estermann, T., & Nokkala, T. (2009), University autonomy in Europe: Exploratory study. Brussels: European University Association.

Estermann, T., Nokkala, T., & Steinel, M. (2011), University autonomy in Europe II. The Scorecard. Brussels: European University Association.

Feldfeber, M., Graizer, O., Gluz, N., Saforcada, F., Caride, L., Imen, P., & Grad, P. (2009), Autonomia y gobierno de la educación: perspectivas, antinomias y tensiones. Buenos Aires: Aique Grupo Editor.

Fernadez Lamarra, N. F. (2003b), La educación superior argentina en debate: situación, problemas y perspectivas. Eudeba. lESALC / UNESCO, Ministerio de Educación, Ciencia y Tecnología de la República Argentina. Retrieved online on 17 December 2013: Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001494/149464so.pdf.

Fernández Lamarra, N. (2003a), La educación superior en la Argentina. lESALC / UNESCO.

Fielden, J. (2008), Global trends in university governance. Education Working Paper Series, 9.

García de Fanelli, Ana. (2007), La reforma universitaria impulsada vía el financiamiento: Alcances y limitaciones de las políticas de asignación. Espacio Abierto, enero-marzo, 7-29.

García Guadilla, C. (1996), Conocimiento, educación superior y sociedad en América Latina. Centro de Estudios del Desarrollo, Cendes-Editorial Nueva Sociedad, Caracas, Venezuela.

Davis, Gerald F. & Cobb, Adam. (2010), Corporatios and economic inequality around the world: The paradox of Hierarchy, Research in Organizational Behavior, 30: 35-53.

Gray, D. E. (2009), Doing research in the real world. Sage.

Greco, C. (2009), Financiamiento de las Universidades Nacionales. Modelos de asignación presupuestaria. Análisis y tendencias actuales. Estado, gobierno, gestión pública: Revista Chilena de Administración Pública, (6): 8.

Griffouliere, María Gabriela. (2008), Sentido del concepto de autonomía y significado actual en el ámbito universitario. Artículo Mendoza, Retrieved online on 13 February 2014: Available at: http://bdigital.uncu.edu.ar/2310.

Kohtamäki, V. (2009), Financial Autonomy in Higher Education Institutions-Perspectives of Senior Management of Finnish AMK Institutions. Tampereen yliopisto.

Leisyte, L. (2007), University governance and academic research: case studies of research units in Dutch and English universities. University of Twente.

Lodico, M. G., Spaulding, D. T., & Voegtle, K. H. (2010), Methods in educational research: From theory to practice (Vol. 28). John Wiley & Sons.

Löscher, A., & Dannemann, G. (2004), Developments in University Autonomy in England (Doctoral dissertation, Master’s dissertation, Centre for British Studies Humboldt University at Berlin, Germany).

Marsiske Schulte, R. (2004), Historia de la autonomía universitaria en América Latina. Perfiles educativos, 26(105-106): 160-167.

Mazzola, C. (2008), Institutional crisis in the Argentine University. Avaliação: Revista da Avaliação da Educação Superior (Campinas), 13(1): 89-100.

Merriam, S. B. (1988), Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. Jossey-Bass.

Ministerio de Economia. (1999), Ley marco de regulacion del Empleo Publico Nacional No 25.164, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Ministerio de Economia. (1992), Ley de Administracion Financiera y de los Sistemas de Control del Sector Publico NAcional No 24.156, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Ministerio de Educación. (1997), Ley de Educación Superior No 24.521 y decretos reglamentarios, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Ministerio de Educacion. (2005), Ley de Financiamiento Educativo, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Mollis, M. (2008), Las huellas de la Reforma en la crisis universitaria argentina. E. Sader, H. Aboites y P. Gentili, Le reforma universitaria, 86-103.

National Constitution of the Argentinean Nation.

Nosiglia, M. C. (2004), Transformaciones en el gobierno de la educación superior en Argentina: Los organismos de coordinación interinstitucional y su impacto en la autonomía institucional. Facultad de Ciencias Humanas, Universidad Nacional de San Luis.

Ordorika, I. (2003), The limits of university autonomy: Power and politics at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Higher Education, 46(3): 361-388.

Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (2003), The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. Stanford University Press.

Raza, R. (2009), Examining Autonomy and Accountability in Public and Private Tertiary Institutions. Human Development Network, The World Bank. Available at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTHDOFFICE/Resources/54857261239047988859/RAZA_Autonomy_and_Accountability_Paper.pdf. Eriflimtarihi, 21(03), 2011.

Ruiz, Guillermo & Cardinaux, Nancy (compiladores). (2010), La autonomía universitaria: definiciones, normativas y jurisprudenciales en clave histórica y actual; Derecho y Ciencias Sociales. Fondo Editorial de Derecho y Economia (FEDYE).

Santos, B. (1998), De la idea de universidad a la universidad de ideas. Bogotá, Ediciones Uniandes.

Serrano Garcia, J. M., & González Villanueva, L. (2012), Debates y perspectivas sobre la autonomía universitaria. Revista electrónica de investigación educativa, 14(1): 56-69.

Slaughter, S. and Leslie, L. (1997), Academic Capitalism: Politics, Policies, and the Entrepreneurial University. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Tremblay, K., Basri, E., & Arnal, E. (2008), Tertiary education for the knowledge society (Vol. 1). Paris: OECD.

Vizzio, M. A. (2004), Eficiencia y equidad en el financiamiento universitario argentino. Revista de Economía y Estadística, 42(1): 161-206.

Yin, R. K. (2010), Qualitative research from start to finish. Guilford Press.