NEW PUBLIC MANAGEMENT IN HIGHER EDUCATION - INTERNATIONAL OVERVIEW AND ANALYSIS

New Zealand

Andrew Traveller

1) Introduction

Setting the New Zealand Scene

New Zealand is a small, developed country with a stable political environment located in the South Pacific. Its population is the third smallest within the OECD (OECD, 2008) with a little more than 4 million inhabitants (Statistics New Zealand 2012) spread sparsely over two main island.

New Zealand underwent a major economic transformation during the 1980’s, transitioning from a welfare state to become an early pioneer of neo-liberalism, with successive governments pursuing a more market-oriented agenda of liberalisation, deregulation, privatisation and fiscal austerity (Kelsey, 2000). As a result, New Zealand was transformed from one of the most regulated economies in the OECD to arguably one of the least (Brash, 2006). This saw it become an early pioneer of New Public Management (NPM), which will be outlined later.

Naturally, this transformation had ramifications for the tertiary education sector. The result was broader participation (massification), increased competition and a reduction in public expenditure on tertiary education, very much in line with the ideals of NPM. These factors represent the general trend in higher education development in New Zealand since the economic reforms. The main implication of these changes was how the tertiary education sector was funded and a shift in focus from input to output orientation. Tuition fees were the main revolutionary vehicle used to broaden participation, increase competition and reduce public expenditure on tertiary education (McLaughlin, 2003). Fees were introduced in 1990. These fees took the form, and continue to, of a governmentally-sponsored, income-contingent student loan program to help cover tuition, course and living costs. Repayment is made through the tax system. Research & Development (R&D) also underwent the same liberalisation as the rest of the economy, creating a more lean and competitive sector. R&D concessions were abolished, public R&D work was subject to cost-recovery arrangements and contestable R&D funds were set up.

More broadly, New Zealand’s tertiary education sector can be described as diverse. It encompasses all forms of post-compulsory secondary education including academic and more vocationally oriented education, with a diversity of institutional forms (Tertiary Education Commission, 2012). With over 900 institutions, the New Zealand tertiary education sector is a mixture of small and large, comprehensive and specialised, and private and public providers catering for over half a million predominantly domestic students (OECD, 2008).

Given this diversity and for the sake of clarity and focus, this paper, i.e. the equaliser analysis, will refer predominantly to academic institutions, specifically the universities. In New Zealand this includes eight universities, which together receive approximately 40% of their funding from the public purse (Universities New Zealand – Te Pōkai Tara, 2012) and can all be considered “public” higher education institutions (HEIs). The remaining income is derived more or less equally from student fees and other sources, such as research contracts and trading income (Universities New Zealand – Te Pōkai Tara, 2012).

New Public Management

Briefly, NPM can be described as the adoption of private-sector management techniques to reform public administration and management (Larbi, 2003). As an early adopter on NPM, New Zealand’s reasons for this were largely in line with the general theoretical drivers or pressures to adopt NPM, namely; economic and fiscal pressures, public criticism, right-wing politics, the proliferation of management ideas, globalisation and the growth of ICT (Larbi, 2003).

Christopher Hood (1991) neatly outlines the key doctrines of NPM thus; hands-on professional management in the public sector, explicit standards and measures of performance, greater emphasis on output controls, shift to disaggregation of units in the public sector, shift to greater competition in the public sector, stress on private sector styles of management practice and a stress on greater discipline and parsimony in resource use.

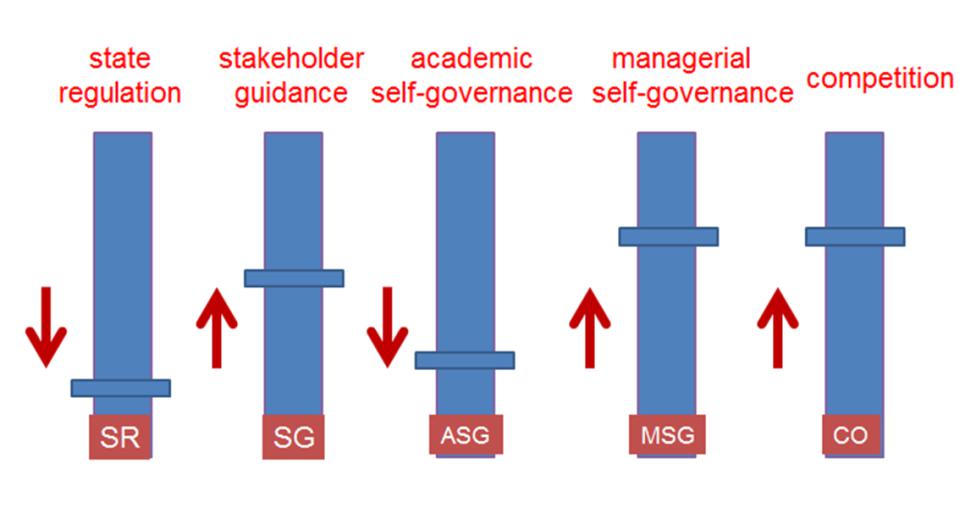

The Governance Equaliser

In order to analyse the governance of higher education systems in light of NPM, de Boer et al (2007) have devised the concept of a Governance Equaliser. They distinguish five dimensions that can be turned up or down to create an optimal mix, much like an audio equaliser. The five dimensions are: state regulation, stakeholder guidance, academic self-governance, managerial self-governance and competition.

According to the NPM doctrine, the optimal mix for the governance of HEIs is depicted in the diagram below (Ziegle, 2012).

2) The New Zealand Mix

New Zealand’s higher education landscape can also be analysed according to the Governance Equaliser. This paper will proceed to do so through three lenses; past, present and future expectations.

A) State Regulation

Past

The aforementioned market reforms of the ‘80s saw HEIs derive a high level of autonomy from the state, with the state exercising little monitoring or input. In other words, during the ‘80s and ‘90s, the state took a so-called ‘hands-off’ approach to the higher education sector (McLaughlin, 2003).

Government funding provides a good example of this distance between HEIs and the state. Funding was reduced, moving from an elite funding system, whereby a limited number of students were funded at a higher level, to a more mass funding system, whereby more students were funded at a lower level with private contributions expected to make up the difference in operating costs (McLaughlin, 2003). For the first time in New Zealand higher education history, HEIs were expected to set fees (up to a limit) and generate other sources of income. This resulted in the massification of participation in the sector and simultaneous state cost constraint, both symptoms of NPM. However, the state was still active in funding the sector through the purchasing of student places (Locke, 2001). In other words, HEIs’ state funding was based on the number of Equivalent Full-Time Students (EFTS) enrolled.

State interests were nevertheless represented through a high number of Ministerial appointments to HEI governing councils. In fact, university councils were historically large with a high number of state appointees (McLaughlin, 2003) - not necessarily civil servants. This is somewhat at odds with the NPM notion of a private sector governance model, which emphasises smaller boards or councils and broader stakeholder representation through the election of stakeholder representatives (Biogen idec, 2012).

Present

Although there continues to be an emphasis on a market-based, or NPM, model, the state now has an increased regulatory function. The rationale for this is that central steering, coordination and strategic alignment with national objectives would support the country’s economic and social development (McLaughlin, 2003). This can be attributed to Labour’s electoral victory in 1999, who posited the notion of central steering in both their campaign and policy pledges and a subsequent Tertiary Education Advisory Commission (TEAC) report, which was delivered in 2002 (Tertiary Education Advisory Commission, 2001). As a result, under the current regime the state exercises control over HEIs by requiring them to produce a Charter, or strategic plan, that aligns with the national Tertiary Education Strategy (TES) (Tertiary Education Commission, 2012). The Education Amendment Act (2003) stipulates that an HEI’s governing council must have regard to the TES. This shift to increased state regulation is often referred to as the 2003 Tertiary Education Reform (TER).

However, an OECD report (2008) appropriately pointed out that “compliance is not synonymous with achieving nationally set goals”. The argument is that instead of truly achieving the desired outcomes stated in a university charter or the national TES, there tends to be an over-emphasis on details and compliance. In other words, the risk of requiring HEI charters to align with the national TES is that HEIs may tend to only include state-mandated strategic priorities as a matter of formal, documented compliance rather than making a concerted effort to realise these goals.

This increase in state regulation runs contrary to NPM and has the potential to be rather burdensome. For example, under current legislation the state has the right to directly intervene in the governance of an HEI. Firstly, it may take positive and supportive action at an early stage if it perceives a failure of governance on the part of the HEI. Following this, the state may appoint a Manager to the council, after which time, if the perceived issues are not adequately addressed, it may dissolve the council and appoint a Crown Commissioner. However, it may be argued that such cases are rare, if ever.

Another criticism with this regulatory approach is that it runs contrary to the flexibility and adaptability required of HEIs, which operate within a competitive globalised market. Even though HEIs are free to determine how they interpret and implement the TES, they are still constrained by the parameters of this state imposed strategy and therefore may not adequately adapt to opportunities and threats from the market in which they operate. However, one would find it difficult to find examples of this.

Due to criticisms that HEI councils were excessive in size and composed of an unjustified number of internal stakeholders and Ministerial appointments (Edwards, 2003), HEI councils today are smaller in composition, with 16 members on average across the sector (Edwards, 2003), and balanced in terms of stakeholder representation, which will be discussed further in the next equaliser dimension.

More broadly, the hands-off approach of the past caused the state to become concerned with the risk profile of HEIs. The aforementioned lack of monitoring of HEIs represented a significant liability to the state’s approximately $3 billion investment in the sector (Edwards, 2003). Consequently, HEIs are monitored and evaluated much more closely these days than they were in the past. The Tertiary Education Commission (TEC) was set up in 2003 to provide advice to the government on the activities and performance of HEIs (Tertiary Education Commission, 2012).

One explanation for this increased government assurance process comes from the theoretical underpinnings of NPM, specifically Public Choice Theory. Public choice theorists have criticized bureaucratic governments of lacking cost consciousness because of the weak links between costs and outputs (Niskanen, 1968). In other words, the state could be criticized of neglecting their constituents by not adequately ensuring value for tax-payer money. According to such economic theory, the government is compelled to closely monitor HEIs to ensure quality and value.

This may also help to explain the change in funding model from one based on the number of EFTS, to a more performance-based system today. The majority of state funding for universities now comes through a performance-oriented Investment Plan, including a Student Achievement Component for teaching and learning, and from the Performance Based Research Fund. To put it simply, HEIs compete for funds and are assessed according to a variety of elements, including quality evaluation, research degree completion, types of programmes or courses on offer, external research income, and number of valid enrolments. HEIs are then funded on the basis of their performance, resulting in increased competition between HEIs for state funds. This fits neatly with NPM theory, which espouses a performance-based, or outcome-driven orientation.

Future

New Zealand’s current right-wing government led by the National party is in its second term and showing no signs of losing favour with the public (Colmar Brunton, 2012). The fundamental philosophy guiding National’s tertiary education policy is the use of tertiary education to build a stronger economy (New Zealand National Party, 2011). It is safe, therefore, to assume that tertiary education will be increasingly instrumentalised to realise economic and labour market goals. This will require continued government steering and regulation in order to link HEIs’ outcomes with state-determined goals.

The question is how the government will do so. It is safe to conclude that the preferred way for the state to steer HEIs is more of the same, i.e. performance monitoring linked to funding. In fact, the National party’s tertiary education policy explicitly states that it aims to “link funding to educational performance…” (New Zealand National Party, 2011).

Additionally, a more direct link between university graduates and the labour market is another way in which the state will use tertiary education to realise its economic agenda. It can therefore be envisioned that students will be steered towards certain fields, possibly through the use of financial incentives, the access to information about what qualifications are deemed employable and even a restriction on courses that may not be viewed as contributing to the state’s agenda. Again, National’s policy statement clearly alludes to this, stating that they intend to “…publish employment data for graduates of each qualification, and simplify the number of qualifications on offer” (New Zealand National Party, 2011).

The question remains as to what the long term consequences of these actions will be in terms of social and cultural impacts.

B) Stakeholder Guidance

Past

The 2003 TER vowed to better “meet the education and training needs of stakeholders on a regional and national basis” (Tertiary Education Commission, 2012). Consequently, this translated into strong stakeholder representation on governing bodies, particularly better inclusion of external stakeholders (Edwards, 2003). We have already seen that prior to this, HEI councils were large, comprised a high level of Ministerial appointments and additionally included an “unjustified” amount of internal stakeholders, such as students and staff (Edwards, 2003).

The post-reform approach to stakeholder inclusion in the higher education sector can be described as the stakeholder governance approach (Edwards, 2003). This means that HEI governing bodies, such as a university council, are accountable to a broad range of stakeholders as opposed to shareholders (as would be the case for private-sector governance models) or purely government (as would be the case for other public entities). The implications of this were that HEI councils included a diverse array of stakeholders and were, and continue to be, judged on a broader range of criteria, including impacts on human capital and communities (Edwards, 2003).

This is also connected and can be explained by the aforementioned point regarding Public Choice Theory, which I think holds true in the New Zealand context. It can be argued that as publicly-funded institutions, HEIs are accountable to the community of tax payers, and therefore are obliged to include external stakeholder representation on its governing body.

Another key historical player of the New Zealand stakeholder landscape is the Maori population. Maori are New Zealand’s indigenous people, and according to the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi (1840), the government, and its associated public entities, are duty-bound to consult with Maori and Maori are expected to be given the full rights of citizens (State-Owned Enterprises Act, 1986). Accordingly, Maori have played an increasingly larger role in higher education in New Zealand (Ministry of Education, 2005), including in the management and strategic development of HEIs (Durie, 2009). For example, Maori are well represented on HEI councils. However, under most university governance arrangements, Maori do not have dedicated seats.

Present

As a result of the aforementioned TER, HEIs continue to have strong stakeholder representation on their councils. Having reviewed the 8 universities’ council constitution, it is fair to conclude that, in general, HEIs reserve seats for specific stakeholder groups as well as for fixed members, such as the Vice-Chancellor. These groups elect a representative to join the council. Ministerial appointments are now limited to four members.

Maori continue to play a role in the governance of HEIs in order to represent their tribal people or bring a wider Maori voice to the table. Again it is important to note that Maori involvement and guidance is not mandated by law or institutionalised by HEIs. Generally, Maori participation is achieved through council membership, advisory bodies, executive-level positions and through government and industry steering committees (Durie, 2009). For example, The University of Waikato has a tribal forum, Te Rōpū Manukura, made up of representatives from the eight major tribes in the region. The Forum acts as an advisory body to the Council and ensures that there are open channels of communication between the several Māori communities and the University. However, a key challenge for Maori stakeholder representation is the difficulty in finding willing and able Maori to take on such roles (Durie, 2009).

As mentioned, with the increasing instrumentalisation of higher education in New Zealand to meet economic goals, there is an increasingly strong link between HEIs, industry and businesses, with research and innovation seen as key drivers of economic growth (Key, 2011). For example, the commercialisation and industrial application of research has long been a focus for the universities. The trend is for HEIs to own commercialisation companies that act as a conduit between their research activities and business. Viclink in Wellington and UniServices in Auckland are two examples of such commercialisation arms.

Future

A key challenge that one may envision for the future in relation to stakeholder guidance is New Zealand’s projected demographic diversity. Statistics New Zealand (2011) predict that between 2006 and 2026, the broad Asian, Pacific, and Maori ethic populations will grow faster than the New Zealand population overall. It can therefore be reasoned that HEIs will be required to be increasingly attentive to this widening array of stakeholders, who will be both internal stakeholders such as students and staff, and external stakeholders representing the community that HEIs serve. With no explicit policies related to this from the current government, it is anybody’s guess as to how this will take effect. I can imagine that as various ethnic groups increase, their presence in executive and non-executive level positions will be a natural consequence.

Importantly, with the change in ethnic diversity in New Zealand, Maori are projected to represent 16% of the population (Statistics New Zealand, 2011), an increase from their current proportion. Coupled with Maori’s increasing economic and political influence in New Zealand as a result of historical land and resource settlements and strong party representation in parliament, it can be fairly surmised that this may result in binding requirements for Maori representation on the governing bodies of HEIs.

C) Academic Self-Governance

Past and Present

In line with NPM theory, which allows for a stronger and more decisive management, New Zealand HEIs have historically had, and continue to have, low academic self-governance in terms of the faculty’s formal and institutionalised decision-making authority. Rather, the Academic Senate have a mere advisory role. It can be concluded that this is a result of the market reforms and the adoption of NPM, as mentioned earlier. Consequently, HEIs follow a more corporate model whereby an HEI’s administration has more decision-making authority than the Academic Senate.

Little has changed in terms of how the Academic Senate is given a voice in HEIs. Although primarily an advisory body, mechanisms are in place to allow the Senate input into matters of HEI governance. First and foremost, the Education Act (1989) determines that the Council will establish an Academic Board/Senate as a sub-committee of the Council. The Council cannot make any decisions in relation to academic matters without first consulting the Senate, being obliged to request and consider its advice on matters relating to courses of study or training, awards, and other academic matters (University of Auckland, 2012). However, as an advisory body the Senate can only exercise power if delegated by the Council (Edwards, 2003).

A strange phenomenon in New Zealand is that although the principals of NPM have been in place for decades, which clearly restrict academic self-governance, the state and HEIs continue to espouse the value of academic freedom and allude to its existence. For example, the University of Auckland’s Charter states that “…academic freedom is exercised…” The Education Act also states that “academic freedom and the autonomy of institutions are to be preserved and enhanced”. However, it also states that “academic freedom and autonomy are to be exercised in a manner consistent with the need for accountability by Tertiary Education Institutions (TEIs) and the proper use by the TEIs of the resources allocated to them.” So we see an inherent conflict between the desire to uphold academic freedom and autonomy on the one hand and the lack of academic self-governance coupled with the state’s increased ability to intervene on the other.

One explanation for this could be that despite the Senate’s lack of formal decision-making authority, HEIs’ management are required to act in good faith when responding to the voice and demands of the academic staff. Establishing and maintaining good faith relationships is the basis of the employment relations system in New Zealand, for both collective and individual arrangements and is a requirement of the Employment Relations Act (MoBIE, 2012). This means that HEIs, as employers, must be responsive and communicative when considering proposals from their employees. Ideally, this should allow the faculty the right to preserve their autonomy, albeit only according to a soft, psychological contract. However, the concept of good faith in a broader legal setting is not sufficiently supported by NZ case law (Bayley, 2009) and therefore this explanation can only be made in relation to the employment relationship between an HEI and its academic staff.

Another way in which the Senate’s influence is extended is through legal precedent. A number of court cases exist whereby an HEI’s Council has been successfully legally challenged for inadequate consultation with the Senate. For example, the University of Waikato was taken to the High Court following a restructure in 1999 for failing to follow correct governance procedures (Locke, 2001).

Future

As aforementioned, the future demands of an HEI will most likely be to provide skills and training to meet national productivity and economic goals and industry needs. With such a predefined focus, it is fair to conclude that academic self-governance, whereby academics are free to allocate time and resources to their own agendas, will therefore be less of a priority. On that basis, it can be expected that the current status quo will not change.

One factor that could impact this stagnation is the demand for HEIs in New Zealand to harmonise with other regions in the world. Peer-reviewed research output is increasingly important, particularly in relation to the existing world rankings (Altbach, 2010) and research-based funding model. Therefore, if HEIs are to compete in a globalised and competitive world market, due support and freedoms will need to be given to academic staff. In this context, the Senate’s voice may get louder and more influential.

D) Managerial Self-Governance

Past

Managerial self-governance is inversely related to the first equaliser dimension, state regulation, in that the less the state intervenes in the governance of HEIs, the more managerial autonomy the HEIs have. This is certainly true in New Zealand. Therefore, I will not recap too many of the points I made earlier.

Briefly, the result of the ‘80s market reforms meant that HEIs operated within a market-like environment with little government involvement other than funding, which was also reduced. This meant that HEIs were independent legal entities with responsibility for their own strategic and operational affairs (Tertiary Education Commission, 2012). In other words, HEIs were seen to have a high degree of institutional autonomy, with freedom to determine HR structures, financial regimes, resource allocation and had (and continue to have) ownership of real estate and other assets and infrastructure (Tertiary Education Commission, 2012).

Government oversight of HEI governance and management was basically limited to the high degree of Ministerial appointments to Councils, as previously mentioned.

Present

HEIs continue to have a reasonable degree to managerial autonomy. The TEC explicitly states on their website that it supports HEIs to be “self-improving and self-managing” (Tertiary Education Commission, 2012), and the managerial responsibilities listed previously have not substantially changed. Currently, Councils, and consequently HEI management, are responsible for specifying intuitional objectives and strategies, improving business planning, internal auditing, developing control structures, risk management frameworks, identification of stakeholders, performance information and standards, evaluation and review, and a focus on client service (Tertiary Education Commission, 2012).

However, there has been a slight increase in government oversight, and consequently a reduction of managerial self-governance, as a result of the 2003 TER, which can be characterised by the notion of accountability. This notion very much persists today. It can be exemplified by increased state “guidance” and stricter monitoring of strategic, operational and financial affairs. The rationale from the government was that it wanted to reduce the risk profile of its $3 billion investment in higher education. As mentioned earlier, this is enacted through the use of performance-based funding criteria, institutional audits and a linkage between individual HEIs’ strategic plans and the national TES.

It can be argued that the state’s increased guidance and new powers to intervene in managerial affairs represent a loss in managerial autonomy. Although it can be argued that HEIs still retain a higher level of managerial autonomy relative to international benchmarks (OECD, 2008), and that a greater degree of coordination was necessary to meet national needs (McLaughlin, 2003).

Future

With the global financial crisis and governments the world over seeking to reign in their national budgets, one may reasonably surmise that the NPM doctrine of “doing more with less” will persist in the higher education sector in New Zealand. I would imagine that this will continue to mean transplanting private-sector managerial disciplines into publicly-funded HEIs.

The New Zealand government’s current approach to public sector governance is best described as an investment model, whereby the focus has been on identifying what is core business and mobilising resources to where they deliver the best results and therefore best value for money (New Zealand Government, 2011). It remains to be seen whether this translates into the state increasingly determining such priorities for HEIs or whether HEIs will be given more autonomy to set their own strategic direction and target resources based on their knowledge of their own markets. A balance will likely occur whereby HEIs will retain some autonomy to meet market demand but will be strongly guided by state funding criteria.

E) Competition

Past

As evidenced in earlier sections outlining the market reforms of the ‘80s, New Zealand adopted more competitive, market-based policies for tertiary education. Again, this is very much in line with NPM doctrine. The main objectives guiding policy during this period were; introducing the efficiency of the market, making institutions more innovative and responsive to the market, opening up the market to new private sector providers, increasing student participation and constraining government costs (McLaughlin ,2003).

The main market-type mechanism employed by the government to seek a more competitive higher education sector was the introduction of user charges, or tuition fees. The rationale was that setting a price for the provision of higher education, and thus sharing the cost of service provision with the user, i.e., the students, would mean HEIs would be more responsible and accountable to their customers (Larbi, 2003). Therefore through a focus on service delivery and customer value, HEIs were able to distinguish themselves and compete for students on the market.

As aforementioned, government funding also moved to a demand-driven model, providing funding to HEIs based on the number of EFTS, resulting in significantly higher participation rates in higher education. This compelled HEIs to invest more in attracting students, thus increasing competition.

One explanation for this shift to a more competitive, market-oriented approach can be derived from the principal-agent theory, a key conceptual underpinning of NPM. In brief, the theory advocates greater competition in the public sector in order to reconcile the public’s inability to adequately hold the government accountable as a service provider, in this case the provision of quality higher education. This inability to fully hold HEIs accountable is a result of insufficient information, such as the ability to fully monitor bureaucrats’ behaviour to avoid the pursuit of narrow self-interest. The monopoly characteristics of public services and the huge transaction costs that would be involved in efforts to write and monitor complete contracts are prohibitive (Larbi, 2003). Therefore, competition is encouraged to ensure the more efficient and effective use of public resources.

Present

The question then emerged as to whether or not the market acted in the wider public interest. Judging from the move towards more central steering of today’s model, it seems it did not. As we have seen, the government therefore took, and continues to take, a more centralised approach to the management of the higher education sector in order to ensure that HEIs are responsive to specific market elements that are prioritised by the government. In other words, because the Labour government felt that such free competition lacked appropriate coordination, HEIs today are guided by the state in what is hoped to be a more strategic approach tied to national socio-economic needs. As we have seen, this currently takes the form of HEI charters that are aligned with the national TES.

This could be seen as a reduction in competition in the higher education sector, as HEIs are now required to meet certain pre-defined goals, thus limiting their ability to respond to the market without restrictions.

Another contributor to this relative reduction in competition is the diversity of institutional forms that currently exist in New Zealand. One could argue that if HEIs cater for specific individual markets and are increasingly centrally coordinated, they will be less likely to compete for the same market segment. As mentioned in the introduction, New Zealand higher education sector comprises a high number of intuitional forms, or as the TES 2010-2015 states, “New Zealand has a broad range of tertiary education providers to meet the varying post-school education needs of New Zealanders” (Ministry of Education, 2010). This diversity continues to be a priority, with HEIs encouraged to “focus on what they do best” (Ministry of Education, 2010). In fact, The OECD (2008) saw this institutional diversity as one of the strengths of the higher education system in New Zealand, particularly the fact that HEIs appear to be conscious of the role they play in the bigger socio-economic picture. As a result, one may argue that by focusing on their strengths, HEIs are becoming less concerned with winning market share in other areas, and therefore less competitive.

However, it is worth noting that despite more state guidance, the tertiary education system still encourages competition. As already mentioned, HEIs are essentially forced to fight for funds through the strict monitoring of performance, which informs the state’s investment decisions. Additionally, New Zealand ranks highly in terms of attracting a significant number of foreign staff and students from the international market (OECD, 2008). In fact in 2008, New Zealand was ranked third by the OECD in terms of growth in international students.

Future

The above-mentioned fight for funds ethos is anticipated to only increase under the National-led government. National’s policies for tertiary education state that it plans “to remove differences in funding treatment between public and private providers” (New Zealand National Party, 2011). The rationale is that this will “ensure funding is prioritised at all times to the results achieved, rather than towards who owns the tertiary institution” (New Zealand National Party, 2011). One may therefore reasonably conclude that according to such policies, competition between HEIs will increase, specifically between the public and private sectors competing for funds. Some commentators in Scandinavia, where similar developments have occurred, have argued that this actually represents a move back to an elite system, whereby fewer, supposedly better, institutions are funded at a higher level (Berg, 2012).

On the other hand, the demand for HEIs to “focus on what they do best” will likely result in greater institutional specialisation, which may see a further reduction in competition.

3) Conclusion

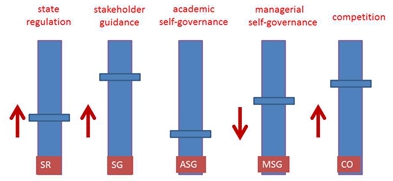

The New Zealand Mix creates a very clear sound from which we can ascertain a couple of key macro-level developments. Namely, it can be seen that New Zealand comes from a background of radical policy reforms aimed at transforming New Zealand from a welfare state with an elite education system to become one of the early adopters of what could be considered NPM, with a strong market-oriented approach characterised by competition and the resultant massification of higher education. This is followed by a shift towards a more centrally steered higher education system aimed at instrumentalising HEIs to meet national socio-economic goals.

This is manifest in the equaliser dimensions depicted below.

Briefly, it can be seen that state regulation has gone from being hands-off to taking a more involved, subtle form of steering. The policy instruments used tend to be soft, rewarding obedient HEIs through the allocation of state funds. Stakeholder guidance has always been strong in the New Zealand mix and continues to be so as a result of ethnic diversity and the demand to be accountable to the tax-paying public at large. Academic Self-governance is valued immensely in New Zealand but has failed to be institutionalised. Rather, it is extended through good faith relationships and legal precedent. As a result of increased state intervention in the higher education sector, managerial self-governance is somewhat diminished from its glory days following the ‘80s reforms. While HEIs are still free to manage their own affairs, they must do so within strategic bounds and prove accountability or suffer from reduced funding or state intervention. Finally, competition has gone from free-market enthusiasm to a more considered approach, with HEIs encouraged to focus on what they do best. However, the fight for funds is still very much a reality.

Furthermore, New Zealand’s small size and culture of stewardship allow pragmatic and direct communication between the government, HEIs and other stakeholders. This has contributed to the willingness to adopt and implement NPM in the higher education sector, and also its ability to adapt and tweak the system in more recent years. We can only speculate as to what may need further tweaking in the future.

References:

Altbach, Philip (2010), The State of the Rankings. Retrieved from: http://www.insidehighered.com/views/2010/11/11/altbach (26.10.2012)

Bayley, J. Edward (2009), A Doctrine of Good Faith in New Zealand Contractual Relationships, University of Canterbury.

Hedda podcast: New Public Management in Sweden and impact on gender, with prof. E. Berg, Podcast, Norway, Higher Education Development Association, 2012

Better Public Services Advisory Group (2011), Better Public Services Advisory Group Report, New Zealand Government.

Biogen idec (2012), Corporate Governance Principles. Retrieved from: http://www.biogenidec.com/corporate_governance_principles.aspx?ID=6062 (26.10.2012)

Brash, Donald (1996, June), New Zealand’s Remarkable Reforms, Address given at the Fifth Annual Hayek Memorial Lecture, Institute of Economic Affairs, London, United Kingdom.

Colmar Brunton (2012), ONE News Colmar Brunton Poll: 15-19 September 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.colmarbrunton.co.nz/images/ONE_News_Colmar_Brunton_Poll_report_15-19_Sept_2012.pdf (20.10.2012)

De Boer, Harry, Enders, Jürgen, Schimank, Uwe (2007), ‘On the Way Towards New Public Management? The Governance of University Systems in England, the Netherlands, Austria, and Germany’, in: Jansen, D. (Ed.), New Forms of Governance in Research Organizations. Disciplinary Approaches, Interfaces and Integration, Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 135-152.

Durie, Mason (2009, June), Towards Social Cohesion: The Indigenisation of Higher Education in New Zealand, Conference presentation presented at the Vice Chancellors’ Forum 2009, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Edwards, Meredith (2003), Review of New Zealand Tertiary Education Institution Governance, New Zealand Ministry of Education.

Fielden, John (2008), Global Trends in University Governance, The World Bank.

Fitznor, L., Goedegebuure, L., Santiago, P. & van der Steen, M. (2008), OECD Reviews of Tertiary Education: New Zealand, OECD.

Hood, C. (1991), ‘A Public Management for all Seasons’, Public Administration 69, 3–19.

Johnstone, Bruce (2009), Financing Higher Education: Who Pays and Other Issues. Retrieved from: http://gse.buffalo.edu/org/IntHigherEdFinance/files/Publications/foundation_papers/(2009)_Financing_Higher_Education.pdf (05.10.2012)

Kelsey, Jane (1995), The New Zealand Experiment: A World Model of Structural Adjustment?, Auckland: Bridget Williams Books.

Kelsey, Jane (2000), Reclaiming the Future: New Zealand and the Global Economy, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division.

Key, John (2011), Science sector set for high-tech transformation. Retrieved from: http://www.national.org.nz/Article.aspx?articleId=37464 (17.10.2012)

Larbi, G.A. (2003), Overview of Public Sector Management Reform, United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.

Locke, S. (2001), ‘Governance in New Zealand Tertiary Institutions: concepts and practice’, Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management, 23 (1), 33-48. DOI: 10.1080/1360080002004725

McLaughlin, Maureen (2003), Tertiary Education Policy in New Zealand. Retrieved from: http://www.fulbright.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/axford2002_mclaughlin.pdf (5.09.2012)

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (2012), Code of Good Faith. Retrieved from: http://www.dol.govt.nz/infozone/collectivebargaining/1-introduction/code-of-good-faith.asp (18.10.2012)

Ministry of Education (2005), Māori in Tertiary Education: a picture of the trends, a report prepared for the Hui Taumata, Wellington: Ministry of Education 2005.

Ministry of Education (2010), Tertiary Education Strategy 2010-2015, Wellington: Office of the Minister of Tertiary Education.

New Zealand National Party (2011), Tertiary Education: Building a Stronger Economy. Retrieved from: http://www.national.org.nz/PDF_General/Tertiary_Education_policy.pdf (17.10.2012)

New Zealand Tertiary Education Commission (2012), Retrieved from: http://www.tec.govt.nz (30.08.2012)

Niskanen, W. (1968), ‘The Peculiar Economics of Bureaucracy’, The American Economic Review, 58 (2), 293-305.

Parliamentary Council Office (1986), State-Owned Enterprises Act 1986. Retrieved from: http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1986/0124/latest/whole.html#DLM98028 (12.10.2012)

Statistics New Zealand (2011), National demographic projections. Retrieved from: http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/estimates_and_projections/demographic-trends-2011/national%20demographic%20projections.aspx (30.09.2012)

The University of Auckland (2011), 2011 Annual Report, The University of Auckland.

Tertiary Education Advisory Commission (2001), Shaping the funding framework: summary report, Wellington: Tertiary Education Advisory Commission.

Universities New Zealand – Te Pōkai Tara (2012), Retrieved from: http://www.universitiesnz.ac.nz/ (12. 10.2012)

Ziegele, Frank (2012, September), New Public Management, Lecture presentation presented for MARIHE, Donau-Universität Krems, Krems, Austria.