NEW PUBLIC MANAGEMENT IN HIGHER EDUCATION - INTERNATIONAL OVERVIEW AND ANALYSIS

Serbia

Vesna Holubek and Miloš Milutinović

Abstract

New Public Management (NPM), the new theory on managing and organizing the work in public sector, has reached the higher education (HE) as well. NPM reforms sparked lively debate within HE community about applicability of these ideas in academic context. Usefulness of NPM for the HE sector primarily comes in a form of analytical tools that can help in defining direction of education system. One of the most prominent analytical concepts, which emerged simultaneously with NPM, is governance perspective - specifically the governance equalizer - developed by de Boer, Enders and Schimank (2007). The paper analyses the governance mode of HE system in Serbia using the governance equalizer. This is done by positioning Serbia on five dimensions of governance (state regulation, stakeholder guidance, academic self-governance, managerial self-governance, and competition) and examining past, present and future expectations. Opinion of HE community in Serbia is also taken into consideration in outlining the governance mode in Serbian HE sector.

Keywords: higher education, Serbia, governance equalizer, new public management

1. Introduction

Higher education system is deeply immersed into society, and as a part of knowledge triangle (innovation, research and HE system), often are recognized as a main driver for societal progress and growth. Universities, that play a crucial role in this triangle, are primarily organized to fulfil the need for dissemination and production of knowledge. The way they operate and cope with emerging challenges is essential in fulfilling their purpose. New Public Management (NPM), the new wave of managing and organizing the work in public sector, has reached the shores of universities as well. The main hypothesis in the NPM reform is that ‘more market’ and ‘less state’ in the public sector will lead to greater efficiency and effectiveness of that sector. These “superficial neo-liberal slogans” (‘more market’ and ‘less state’) are often oversimplifying the complex set of ideas that is elaborated in NPM literature (de Boer, Enders and Schimank, 2007, p. 2).

Portraying the direction of NPM changes, Ziegele (2008) contrasts the old and new management models. Old management model is described as oriented toward input and process-political single interventions; a precise “ex-ante” management (Ziegele, 2008). New management model, on the other hand, is oriented towards outcomes and efficiency, within regulatory policy framework; macro “ex-post” management (Ziegele, 2008). NPM applies competition, as it is known in the private sector, to organizations in the public sector, emphasizing economic and leadership principles. Beneficiaries of public services are perceived as customers. NPM ideas are built upon the change in governance perspective introduced in political theory. This change can be described as a shift from regulation to deregulation and open competition, from steering to market, from administration to management.

There is a lively discussion among scholars in HE field about NPM reforms and their applicability in HE area. There are many arguments that speak in favour of NPM reforms in HE. These reforms tackle the problems of inefficiency, over-regulation, bureaucratization and inflexibility of higher education institutions (HEIs). Emphasising accountability and decentralization of HE systems, introducing performance-based funding and enhancing quality assurance processes, NPM is seen as the solution to major problems in HEIs (some of the success stories are UK, Norway, Sweden and the Netherlands).

On the other hand, some scholars do not agree with these ideas and perceive NPM as a “management fad” (Birnbaum, 2000, p. 5) that is borrowed from business sector and artificially imposed on HEIs, thus dehumanising them. The main problems emerging with NPM are commodification of knowledge, turning the university into a “knowledge industry” and student into a consumer. Hence, Ginsberg (2011) claimes that NPM reforms lead to continuing erosion of educational quality and research productivity of HEIs. From this viewpoint NPM is inacceptable approach for the academic world.

There are no definite answers about applicability of NPM in managing the HE sector that can be derived from this debate. Rather, the importance of this discussion between two parallel viewpoints lies in the possibility of alternative thinking about the same subject. Analysing HE systems through ‘NPM lens’ can provide a different framework to reexamine the old problems in a new way. Usefulness of NPM for the sector of HE primarily comes in a form of analytical tools that can help us define the orientation of our education system. One of the most prominent analytical concepts, that emerged simultaneously with NPM, is governance perspective - specifically the governance equalizer - developed by de Boer, Enders and Schimank (de Boer et al., 2007, p.2).

Therefore, the main goal of this paper is analysing the governance mode of HE system in Serbia using the equalizer. This will be done by positioning Serbia on five dimensions of governance looking at the three phases (past, present and future expectations) and pointing out the main trends of developments. Also, to explore some other perspectives on this issue, we gathered several opinions via small questionnaire (see Appendix 1). The participants (7) are people involved or working in HE sector in Serbia.

At the beginning we present the equalizer as introduced by de Boer, Enders and Schimank. Then, we provide an overview of HE system in Serbia through steering documents and numbers. The second section is organized around the five dimensions of governance and the analysis of HE in Serbia. Illustration of governance equalizer in Serbia, tendencies and different opinions are in the focus of the third section. The conclusions are presented in the fourth section.

1.1 Governance Equalizer as Introduced by de Boer, Enders and Schimank

Governance mode in public sector in Europe has undergone a great change since the 1980s. Authority and power has been redistributed under the influence of neo-liberal ideologies. The ‘new’ governance has introduced coordination divided among multiple actors on multiple levels in contrast to the previous coordination where the state was the sole regulator. This change is visible in HE as well, where we see that the state loses its key role and tradition of self-governance. Instead, the network of governance emerges. The main drivers of these changes are globalisation and internationalisation processes, opening towards the market, scepticism toward the state and the need for more efficient use of resources. The rise of NPM has stimulated the rethinking of governance in HE.

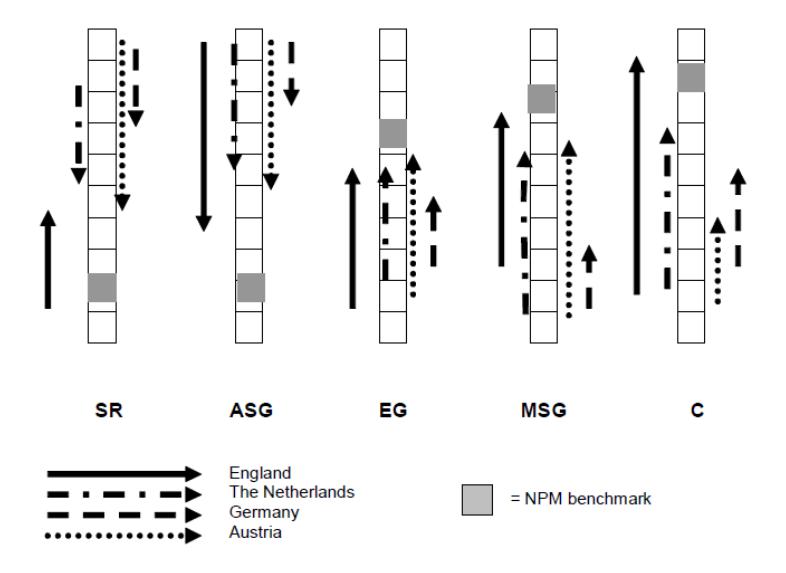

Analysing the challenges which HE encounters, de Boer, Enders and Schimank, have devised “the governance equalizer”. They use this analytical tool to compare changes in university governance of four European countries – England, Netherlands, Austria and Germany (see Figure 1).

De Boer et al. (2007) recognize the above described change in governance mode and argue that governance perspective provides a general analytical framework for studying dynamics of coordination among actors. On the other hand, NPM is understood as normative programme, a specific formula for good policy-making and governance in public sector in general. They remind us that empirical studies and theoretical reflections show that, for certain circumstances and with respect to particular criteria, hierarchical-steering governance is the best mode, while for other circumstances and criteria market-driven governance works best.

The governance equalizer has five dimensions of governance: state regulation, stakeholder guidance, academic self-governance, managerial self-governance, and competition. Developing this distinction of five dimensions, they evoke and build upon Clark’s (Clark, 1983) notion of coordination by bureaucracy, profession, politics and market, adding the dimension of managerial self-governance. De Boer et al. (2007) use the metaphor of equalizer as an electronic device because it allows emphasis of selected frequencies in an audio spectrum, and creative altering of certain frequencies to produce desired tonal characteristics in sounds. Accordingly, the configuration of HE governance is made up of a specific mixture of the five dimensions at a particular point of time. Each of these governance dimensions is independent and can be turned up or down without influencing other four.

State regulation refers to regulation by directives, i.e. detail prescriptions from the government for behaviour under certain circumstances. Here authors denote the traditional idea of top-down authority vested in the state.

Stakeholder guidance dimension concerns involvement of other actors through goal setting and advice (for instance, intermediary bodies or industry representatives). In public university systems the most important stakeholder is government, but not necessary the only one.

Academic self-governance speaks about the role of academia and professional communities in HE systems. Their role is institutionalised through mechanisms like peer review-based self-steering of academic communities or collegial decision-making at universities.

Managerial self-governance concerns organisational hierarchies at the university level – regulation and decision-making of the university leadership (rectors and deans).

Competition within and between universities for scarce resources (personnel, finances or prestige) doesn’t involve real market. Rather, it is, so called ‘quasi-market’, where customer demands are replaced with performance evaluations by peers.

Four European countries compared here – England, Netherlands, Austria and Germany – have articulated NPM as an important goal of the public sector reform. Thus, authors try to measure the actual changes in governance by using NPM as the common normative benchmark for comparison. In that sense the NPM ‘ideal’ on the equalizer would place five dimensions in this manner: state regulation and academic self-governance should be rather low, while stakeholder guidance, managerial self-governance and competition should score high. This means that the state should distance itself from direct control and regulation of HE and focus on goal setting. Also, academics should do what they do best – discover and transmit knowledge – and their role in university governance should be marginal. Market-like competition (although quasi-market) should lead to increase of efficiency and decrease of costs. Instead of controlling the input, the emphasis should be on output control (ex post evaluation and performance). Private sector management techniques should also support increase of efficiency and effectiveness of service delivery. Therefore, excellent managers, with room to act and manage the universities, are needed. Competition for resources between and within universities relies on deregulation and the establishment of a new powerful institutional leadership. Greater involvement of other stakeholders (beside the state) is supposed to establish strategic orientation of the university toward competitive future. It is visible that NPM presents an integrated perspective of overall redirection of governance in the HE system. Authors explore how this redirection to NPM affected HE systems of four countries.

England is often referred to as a forerunner of NPM-inspired reforms in HE sector, which started in late 1970s, followed closely by the Netherlands. Austria and Germany introduced the governance reforms in the 1980s, but actual changes have only very recently become visible. After detailed analysis of four countries and definition of their position on the governance equalizer, authors conclude that governance equalizer is useful analytical tool for comparative approach. It helps us to locate similarities and differences at a single glance.

Figure 1: Governance Equaliser by de Boer, Enders and Schimank (2007)

1.2 Facts About Higher Education in Serbia

The history of the HE in Serbia starts with the University of Belgrade and it can be tracked down to the beginning of the 19th century, when Dositej Obradović founded the College in 1808. During its early history it had three departments: Philosophy, Engineering and Law. After the Second World War the HE system in Serbia went through the period of substantial growth and was diversified by establishing new HEIs.

The communist system in the former Yugoslavia (between 1945 and 1990) was considerably different to that of the countries under direct influence of USSR and it can be described as “worker self-management” (Clark, 1983, p. 45). The consequence of this system is inherited high level of academic self-governance with high influence of the state. After the fall of communism in 1990 came a turbulent period of wars and isolation that lasted until the “democratic revolution” (Erlanger, 2000) in October 2000 and the decade between the 1990 and 2000 is generally perceived as the decade of stagnation for HE sector.

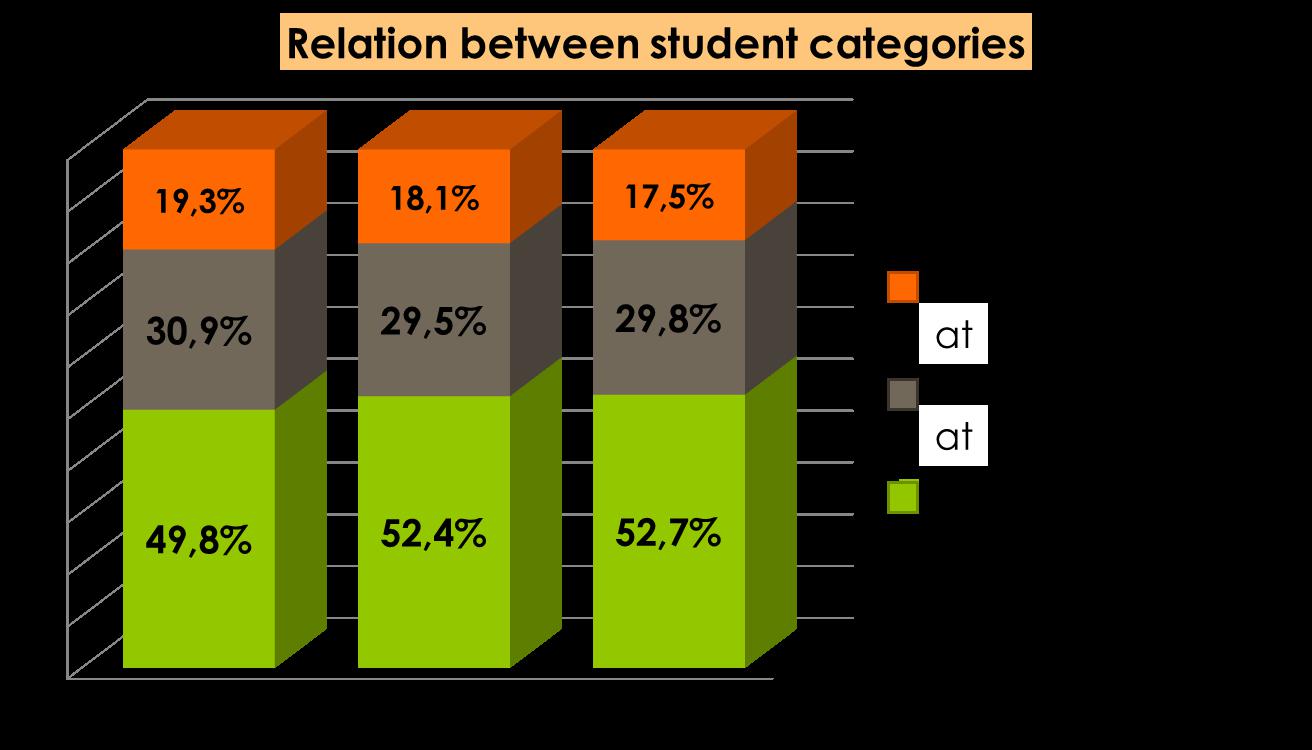

Today, the HE system in Serbia is a binary system, where, according to the way in which HEIs have been established they are either public or private. Both types of HEIs become legal entities within the HE system only after receiving a state permission granted by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development (hereinafter Ministry). According to the database of the Ministry (http://www.mpn.gov.rs/) and the database of the CAQA - Commission for Accreditation and Quality Assurance (http://www.kapk.org/index.php?lang=en) there are 8 public and 11 private universities in Serbia, (around) 80 colleges and faculties of applied sciences, nearly 250.000 students (around 3,5 % of total population) and vast majority of them study in public HEIs. The private HE sector has a large number of institutions, but the percentage of students at these institutions is around 15% of the total student body (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Relation between student categories (public and private universities)

Serbian HE is primarily regulated by the Law on Higher Education which came into force in 2005 (last amended in 2013). HE activities are carried out through either academic or professional career (vocational) studies. System of HE in Serbia is organized through 5 institutions:

1. University (autonomous establishment with managing and professional bodies; lead by rector),

2. Faculty (within the University; includes both teaching and scientific research; provides academic and vocational education),

3. Academy of Professional Studies,

4. Higher Education College of Professional Studies and

5. Higher Education College of Academic Studies.

Public HEIs are funded partially by the state. They are also allowed to collect tuition fees and acquire third-source funding. State funding is conducted by agreement between HEIs and the government, based on accredited study programmes (line-item budget). The ratio between financial resources is not defined by the Law on HE, because the HEIs have the so-called ‘budget autonomy’. The question of the tuition fee is the trigger for the student protests across Serbia almost every year from 2005.

The functioning of the educational system is ensured through several institutions that operate on different organisational level, but all were established by the state – The Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development; The National Education Council; The Commission for Accreditation and Quality Assurance; The National Council for Higher Education; The Institute for Educational Quality and Evaluation; and The Institute for the Improvement of Education.

Public universities in Serbia are: the University of Belgrade (largest university with almost 90.000 undergraduates and graduates), University of Novi Sad (almost 50.000 students), University of Niš (27.000 students), University of Kragujevac (14.000 students), University of Pristina – Kosovska Mitrovica, Public University of Novi Pazar, as well as two specialist universities – University of Arts and University of Defence. Largest private universities include Megatrend University and Singidunum University, both in Belgrade, and Educons University in Novi Sad. University of Belgrade (301-400 place on 2013 Shanghai Ranking of World Universities) and University of Novi Sad are generally considered to be the best institutions of HE in the country.

2. Five Dimensions of Governance in Serbia

Applying governance perspective in analysis of HE system in Serbia we now turn to description of five dimensions of governance: state regulation, stakeholder guidance, academic self-governance, managerial self-governance, and competition. The focus will be on the historical background, current situation and future outlooks of each dimension. The analysis is based on legal documents and scholar papers related to HE topics.

2.1 State Regulation

The current situation in HE is noticeably different compared to that during the turbulent period in 1980s and 1990s. Government established after ‘democratic revolution’ in 2000 restored university autonomy by effectively suspending the Law on University from 1998, which was considered to be regime’s attempt to keep universities under its thumb by giving more power to the Ministry. Article 91 (Law on University, 1998) gave Minister the power to (dis)approve appointments of all full professors, which - considering regime’s previous track record - represented a significant threat to academic freedoms and led to many professors being fired from work or resigning in protest.

It took the new democratic government almost 5 years after October 2000 to adopt the new and truly reform-oriented Law on Higher Education, which has been altered slightly several times since - last time in October 2013. The 2005 Law fully complied with Bologna principles; it had less direct state regulation than previous, and, for the first time, it encompassed the whole tertiary sector – universities and schools of applied sciences. It gave HEIs more academic freedoms and autonomy to decide on their own internal organization and regulations. It gave autonomy to: adopt study programs and rules of study, adopt rules on election of academic staff, regulate their internal organization, issue official documents, and the right and freedom to distribute financial means acquired from public and third sources (Law on HE, 2005, Art. 6). The Ministry still gives final approval on the proposal from the universities on the enrollment quotas, which are usually set in general terms for each university with some maneuvering space. The university management then negotiates and lobbies for the final endorsement. This would present state an opportunity to invest strategically, but so far no needs assessment has been conducted and therefore all decisions are taken on personal basis.

Until the 2005 Law (Law on University, 1998, Art. 135) universities had to ask for approval of the Ministry for their financial plans, so this change was an important step towards less direct state involvement and it provided frame for more managerial self-governance. There can be no real autonomy without financial autonomy. Publicly funded HEIs are financed by the government through a line-item budget that is solely based on inputs (number of students, size and number of buildings, laboratory and library space, etc.) (Bylaw, 2002). Under the letter of the Law on HE the founder (state) should provide universities and faculties means for: upkeep cost, material costs, salaries of academic and non-academic staff, research, literature acquisition, IT systems, international cooperation, funding for gifted students, etc. (Law on HE, 2005, Art. 59). Due to general lack of financial means, government sometimes does not transfer or delays transfer of part of these funds. Universities and faculties have to then use own resources to cover those expenses not covered by the government, which are usually costs of repairs and upkeep (heating, electricity, utilities). As government spending is not transparent, this practice can be used as a measure to keep universities under control. All government funds are transferred as line-item budget and therefore cannot be spent for other purposes, resulting in a ‘December spending frenzy’. Less state control would probably be desirable in this area in future with more ex-post and less ex-ante measures, however, more accountability needs to be achieved first.

On the other hand, public universities and faculties are able to acquire own funding from: tuition fees, donations, commercial and other services as well as contracts with companies (Law on HE, 2005, Art. 57). HEIs cannot, however, start spin-offs and hold shares in other companies but they are free to spend their own funds freely (budget autonomy). Public HEIs are not owners of the land their buildings are located at - it belongs to the state - and this fact makes any (re)construction or trade a bureaucratic nightmare.

Important fact also related to stakeholder guidance and academic self-governance is that faculties are legal entities as stipulated in the Law (Law on HE, 2005, Art. 47). They enroll students and collect tuition fees form self-financing students. Although the university Senate decides on the percentage of funds that will be transferred to the university for its integrative functions (Law on HE, 2005, Art. 48) the financial interest of all the faculties, whose representatives make out 90 percent of the Senate, is to give as little as possible. There are, therefore, very few joint and strategic investments on the university level. As Serbia is the only country in Europe with such regulation, the Ministry is under certain external pressure from the EU to amend the Law but due to high academic self-governance and lobbying from faculties with high percentage of self-paying students these changes were never adopted. Although the current Law does not forbid integrated university, it is unlikely that the situation will change much without direct government involvement (law change).

Another area where we can notice less direct state regulation with adoption of 2005 Law is the introduction of controlling or buffer bodies, which are placed outside of direct control of the Ministry. These bodies are: National Council on Higher Education (NCHE), Commission for Accreditation and Quality Assurance (CAQA), Serbian University Conference (SUC), Serbian Students’ University Conference (SSUC) and they should allow better planning, exercise control, increase the quality and provide sustainable development of Serbian HE system. Under the provision of the Law these bodies serve mostly as advisors for the Ministry.

NCHE consists of 21 members, all of whom are formally elected by the Serbian National Assembly (Law on HE, 2005, Art. 10) allowing, therefore, direct political control on election of this supposedly independent body. 15 members are selected on proposals from SUC and Conference of Polytechnics and 7 members are proposed by the Government. The NCHE is mainly given a consultative role to the Ministry and only real power is setting criteria for accreditation, self-assessment and external evaluation; it also should propose National Qualification Framework to the Ministry and it serves as second instance on appeals to the decisions of CAQA (Law on HE, 2005, Art. 11). NCHE should file reports to the National Assembly once a year (Law on HE, 2005, Art. 12) as a control mechanism by the state. CAQA is directly subordinate to the NCHE as its members are elected by NCHE (Law on HE, 2005, Art. 13). It runs the process of accreditation and self-assessment. It is funded out of fees making it more independent in its decision making but its work is under constant pressure on one side from peers and on the other from the government. The SUC, Conference of Polytechnics and SSUC are consultative bodies that in essence have no real power other that their members are rectors of all accredited universities, directors of polytechnics and student activists respectively.

State regulation of HE in Serbia has in last 10 years gone from meddlesome and obstructive to more equal-partner approach. In some areas such as accreditation state has allowed more academic self-control and transparency – previously mostly private faculties could be set up without fulfilling any standards if the owner had good connections in the Ministry. Accreditation process has, therefore, upgraded the current situation. Still, there are some issues with the process of accreditation that require either more state involvement or more stakeholder involvement, as it is stipulated in the Strategy (2012, p. 176): setting enrolment quotas according to country needs, maintaining register of all lecturers, regulating engagement and workload of lecturers.

In the future it is expected that the overall expenditures for HE – including government spending for student loans, scholarships and tuition fees as well as contributions from self-paying students and from the industry – should increase from the current 0,7 to 1,25 percent of GDP in gradual steps until 2020 (Strategy, 2012, p. 175); this should provide more funds for the HEIs overall, but on the other hand continuous massification foreseen in the Strategy (2012) can also lead to less funds per student, as cost will rise. HEIs will, therefore, need to find additional funding opportunities, some of which they are currently not allowed to use, so gradual loosening of regulation could be expected. As it is laid down in the Strategy the government should provide full funding for the best students; the rest would pay on a variable principle involving past success and economic background. In that respect the government’s control would not change as it already provides soft loans for students but the framework of its involvement may change. State should also require faculties to disclose full costs of tuition in a transparent fashion.

The Strategy also promotes the idea of “entrepreneurial universities” (Strategy, 2012, p. 93) and supports changes in the legislation that would allow universities to set up companies, start-ups, and business incubators and thus promote entrepreneurial spirit of students and academics. This change would promote less state control and more accountability.

2.2 Stakeholder Guidance

Similar to other ex-communist countries traditionally the most significant stakeholder for HEIs was the state, keeping everyone, including HEIs, on a tight leash. Other stakeholders such as students, academics, employers or industry played minor or subordinate role. The prospect of EU accession, process of reforms and deregulation opened new space for their involvement, as well created some new stakeholders: buffer bodies and EU.

As the one who holds the ‘purse strings’ and as main financial contributor government continues to be key and single most important stakeholder for HEIs, but as its financial role diminishes, the importance of other stakeholders gains momentum. The financial rules are laid down in the Bylaw, but the government does not always adhere to it. Inclusion of other stakeholders, like industry, is occasional occurrence and can be attributed more to entrepreneurial spirit of the individuals than as strategic course of action. Study programs are rarely developed with employment in mind, and employers are seldom consulted. The most important aspect of a study program is the demand on the side of students, so the faculty can earn more money. There are recently some examples of industry-driven study programs. The Faculty of Technical Sciences of the University of Novi Sad, for example, has several partnership agreements with companies as well as about 50 spin-off companies (some employing up to 400 engineers) that were started by their professors, thereby circumventing legal restrictions. The specific needs of these companies were incorporated in study programs, and students can go there on internships. The Engineering Faculty of the University of Kragujevac introduced new study program in Automotive Engineering after Fiat started car production in Kragujevac. General problem for Serbia is overall very weak industry that the universities and polytechnics could partner with. Inevitably the role of external stakeholders will grow in the future. Following measures are laid down in the Strategy (2012): CAQA will include academics, students and employers in preparing new sets of standards for accreditation; it will include independent domestic and foreign experts, as well as (again) students and employers in the peer-review process; and it should make peer-review findings available to the public giving a more active role.

Under the previous and current systems students have certain rights and influence. They usually hold 16 percent of seats in the university senate or faculty scientific council but their role is marginalized as they are not perceived as partners but politically-influenced group fighting for privileges. Student organizations, student parliaments and Serbian Conference of University Students are plagued with three main problems: lack of funds, lack of interest of students and interference of daily politics, as some student organizations are nothing more than branches of political parties (Studentska unija Srbije, c. 2011). Students are sometimes used for daily political purposes in a process that can be described as ‘quasi stakeholder-guidance’. An example of this ‘quasi stakeholder-guidance’ would be the most recent amendments in the Law on HE: students demanded the abolishment of articles that would on one hand raise the minimum number of ECTS to be attained in order to enroll the next academic year from 48 to 50, and on the other lower the number of exam periods from 6 to 5 (this was adopted in 2012). Fearing students’ protests government quickly backed down and changed the law ex-post facto on 11 October 2013, 11 days after the enrollment period.

Students surveys are being conducted but they hold no relevance as there is no feedback or evaluation. The Strategy puts the students in the center of the learning process, “student-centered learning” (Strategy, 2012, p. 87), thereby acknowledging their importance as stakeholders. However, measures for its implementation need to be created and it would require students to become more active.

Historically, the most important stakeholder in the area of research for HEIs was the state. According to Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (SORS) (2013) the industrial output in the last 10 years has been stagnating at around 40 percent of its output in 1990 (Industrial production, 2013) so HEIs were progressively looking to state for funding. Large industrial complexes mostly collapsed, privatization brought either foreign owners, who were not interested in research collaboration, or bankruptcy. After the 2000 government has been increasing investments in research and development (R&D) from 27 million EUR a year to 100 million, which hardly broke the 0,5 percent of GDP. Industry involvement at the same time stagnated at around 0,1 to 0,2 percent of the GDP. (SSTD, 2010) The Strategy of Scientific and Technological Development of Serbia for the Period 2010-2015 (SSTD, 2010) clearly states the need to increase in public R&D closer to 1 percent and also to increase third party funding (SSTD, 2010: 3-4). In Seventh Framework Programme (FP7) Serbia was able to acquire 47 million EUR in 7 years and in recent years there were indications of additional government spending aimed towards improving competitiveness of Serbian researchers. According to the Strategy (SSTD, 2010) Serbia still has low number of patents and laws on intellectual property rights are not enforced. Involvement of state and other stakeholders is needed to change this situation. Negotiations with EU are likely to start with the area of Education, as well as Research so harmonization with EU is to be expected. In 2011 the Ministry of Education was merged with the Ministry of Science, a move not widely supported by the scientific community that considered it would be less significant and visible in the new enlarged Ministry. There is danger that due to ongoing economic crisis R&D funding would not increase. EU funding is not enough to make progress, and Serbian institutions are still not competitive enough to attract more funding from EU source. Involvement of external stakeholder will therefore become a priority.

2.3 Academic Self-Governance

As already mentioned, the influence of academia on governance of HE system is very high. Two main reasons for this can be identified in recent history - academic autonomy and worker self-management. Academic autonomy that universities gained after the ‘democratic revolution’ in 2000 increased the influence of the academics in HE system. Combined with the authority of the profession inherited from the previous political communist system (worker self-management), university professors became one the most influential group in HE system in Serbia. The third stream from which authority of academics draws its strength is political and religious orientations imported from the broader society. Here we can call upon Clark’s concept of belief that has strong impact on coordination of HE systems. Specifically, belief that is based on discipline and profession can be recognized in Serbia (Clark, 1983). Professors are being included (in the name of expertise) in various national decision-making bodies claiming the position of university representative, speaking in the name of the university in whole (including students). For example, main controlling and buffer bodies (such as National Council on Higher Education or Commission for Accreditation and Quality Assurance) are mainly composed of members – academics.

Today, situation hasn’t changed much. Since the democratization of the society, the strength of academic oligarchy relies in the academic autonomy. Law on HE defines the autonomy of university as the right to define curriculum and rules of study, enrolment criteria, rules on election of academic staff, to regulate their internal organization, issue official documents, and to distribute financial means acquired from public and third sources (Law on HE, 2005, Art. 6). In all of these areas academics play the crucial role, simply because they have the majority of votes. For example, the detailed rules on election of academic staff are being defined on the level of university by the academics sitting in the University Council and deciding upon the Statute (Law on HE, 2005, Art. 64). Representatives of students, state and non-teaching staff are present on the University Council meetings, but are usually outvoted by the majority of members – academics. In this way, academic staff decides who is suitable to become ‘one of them’. This example also shows how other stakeholders, such as students, industry, employers, and, in some issues even the state, are still not perceived as an important decision-making partners.

In the future, based on the Strategy (Strategy, 2012), a slight decrease of influence of academics on HE system is expected. Introduction of European dimension in HE is the main impulse for this. Quality assurance and quality enhancement processes, set as one of the priorities for the future HE, recognize the need for competence improvement of academic staff and transparency of decision-making within university. Also, the Strategy defines stricter performance-based appointment of professors. Increasing mobility of students and lecturers and experiencing other systems, is also one of the priorities set for the future which can ‘shake’ the established belief in undisputed authority of university professors. Introduction of other stakeholders in the decision- and policy-making processes, as well as strengthening university leadership (management) are recognized in the Strategy as important factors in modernising HE (Strategy, 2012). Thus, increase of these two dimensions (stakeholders and management) can also provide significant support for decrease in academic self-governance. However, this transition might be difficult, due to long-lasting establishment of the current functioning. The second setback could be the peer-review based evaluation which is often used as a quality measure.

2.4 Managerial Self-Governance

As it has been already mentioned the influence of relatively high and restricting state regulation, combined with high academic self-governance in the past has been impeding raise in managerial self-governance in Serbian HE. The form of authority in HE system in Serbia is a mixture of personal and collegial rulership, with the emphasis on the latter. Clark (1983, p. 111) argues that “[if] the formal system places a chaired professor in charge of a domain of work and then does not enforce its many laws and codes through checking-up procedures that would detect deviation - typically not done in HE - it invites avoidance of rules.” This is something that can be observed in Serbia all too often. Central to the collegial rulership, on the other hand, is the appointment from below, from within a body of peers, but this usually results - as it is case in Serbia - in amateur administration. Thus, the level of managerialism is essentially dependent on one’s personal capabilities rather than institutional setting. Rectors, as well as deans, are always aware of the fact that they are dependant on peer support to get their ideas through. Senior faculty memebrs and members of the Senate, who are often rather conservative in their opinions, vote on almost all important matters, including management´s term in office (Clark, 1983), which is enough to throw cold water on any ‘hot’ reform-oriented idea.

The Law on HE only helps maintain the current low level of managerial self-governance as it allows faculties to remain legal entities, financially independent from the university, which as a consequence has weak university management. The degree of managerial self-governance on the faculty level, where the deans do have some power of authority, is not much higher either - with several notable exceptions mentioned in section on stakeholder guidance. The academic self-governance and collegial rule are deeply entrenched in the statutes and bylaws, as well as minds of some professors, for whom the period of worker self-management never really ended. There are numerous councils (electoral, scientific), even more committees (ethics, financial, QA, investments etc.), scientific boards (for each field of science) and several consultative bodies that debate, dilute and maintain the status quo.

The current Serbian HE system, that can be described as slow-reacting, conservative, and restrictive, is placed in a dynamic and fast-changing environment of European Higher Education Area. As financial autonomy rises so should the responsibility and accountability for own future. Strategy (2012) emphasizes Quality Assurance and self-assessment mechanisms. It mentions the concept of “entrepreneurial university” (Strategy, 2012, p. 93) but does not elaborate on it any further. Several TEMPUS projects in recent years (Towards a more sustainable and equitable financing of higher education in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro (FINHED), Building Capacity for Structural Reform in Higher Education of Western Balkan Countries (STREW), and Governance and Management Reform in Higher Education in Serbia (GOMES)) have been tackling the issue of governance of universities but without concrete results and system changes. It can be therefore concluded that it will take some time or some strong new impetus to raise the current level of managerial self-governance. Still, it is questionable if this would actually be desirable and would lead to better management overall as there are many examples of problems in direct translation of new management ideas in different settings.

2.5 Competition

Dimension of competition has had a minor influence on governance mode of HE in Serbia in the past. A significant change happened in the recent history. After the democratic changes in 2000 we can recognize a glimpse of ‘quasi-market’ in establishing private HE sector. Majority of private universities that are still operating were founded after 2000. For instance, Singidunum University, Union University and Metropolitan University in Belgrade were founded in 2005, and Educons University in Novi Sad in 2008.

Today, impact of quasi-market in HE is relatively big. Competition for scarce resources is visible between public universities, as well as within. An attempt to analyse the functioning of competition, between and within universities in Serbia, led us to a relevant study. Education Policies Centre has conducted a research “The working conditions of teaching staff” in 5 faculties within the University of Belgrade (the biggest public university in Serbia) in 2008 (Jarić, 2009). When interviewed about day-to-day functioning of the University of Belgrade, teaching staff diagnosed the current situation as “defragmentation”. They described defragmentation as present on every level – of universities on national level; of faculties on level of one university; and, on departmental level within faculty (Jarić, 2009).

We see defragmentation as the main driver-force for competition. Defragmentation is reflected in lack of cooperation and common strategic orientation. Some of the words used to describe this phenomenon are also “institutional isolation” and “atmosphere of autarky” (Jarić, 2009). Defragmentation leads to a specific kind of competition (unproductive competition) where units compete for resources not by defining their specific institutional profile, nor providing better quality and service. Rather, they call upon the established authority based in tradition and historically gained reputation. We see this as a legacy of communist worker self-management.

One of the alarming consequences of this unproductive competition is continuous ‘brain-drain’ that started during the 1990s. Defining the current situation of HE, Strategy diagnoses this problem and proposes a measure: improvement of HE quality by developing quality assurance system and intensifying competition (Strategy, 2012, p. 106).

There are some indications of change toward quality improvement in HE stimulated by private sector and opening to EHEA. Private universities offer modern, competitive curricula and greater student mobility steering the education towards market demands. There are different (often opposed) opinions about the impact of the private HEIs on the quality of the education as well as of learning outcomes. Opponents of private HE criticize consumerist character of private universities. On the other hand, private HEIs provide better condition for the advancement in science due to financial organisation and produce competitive professionals. This is an on-going debate with no definitive answers. However, it is evident that private sector stimulates competition and forces public universities to position themselves on emerging quasi-market. Second impetus for profiling of HEIs comes from competition within EHEA. Not just domestic, but also the foreign players will expand quasi-market and competition will play more important role in governance mode of HE system in the future.

Establishment of entrepreneurial universities and further internationalisation of HE (international study programmes and so called ‘brain circulation’) are also actions proposed by the Strategy, which will additionally sharpen the competitive edge of universities in Serbia (Strategy, 2012, p. 93&122).

3. Governance Equalizer in Serbia

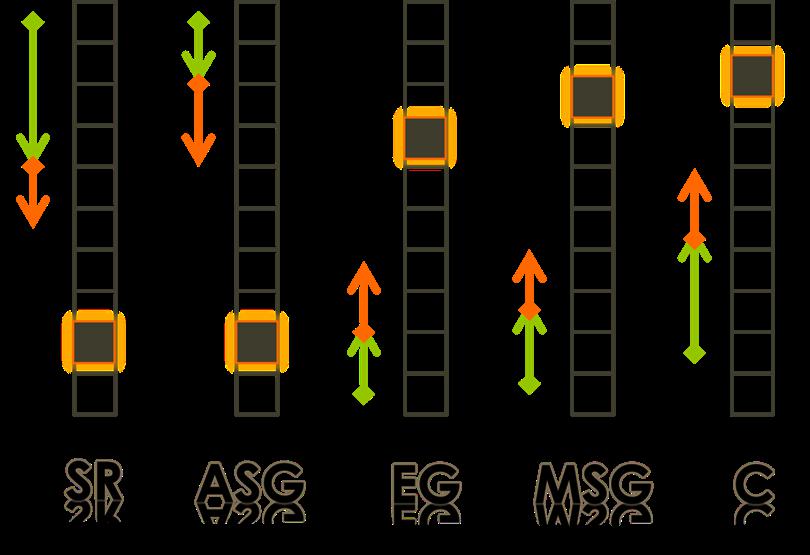

Based on fairly detailed description of HE system in Serbia we designed the governance equalizer. Using this analytical tool we tried to visually encompass the five dimensions of governance mode in the past, present and future (see Figure 3).

The beginning of the arrows (green square) presents respective dimension of governance in the past – year 2000. Our description sometimes goes further back in the past due to estimation that historic background is needed. The current situation (2013) is represented by the point where the green and orange arrow meet. Length of the arrows shows the degree of change in respective dimension.

SR: State Regulation

ASG: Academic Self-Governance

EG: External Guidance

MSG: Managerial Self-Governance

C: Competition

à Past and current state

à Future outlooks

NPM benchmark

Figure 3: Governance Equalizer in Serbia

3.1 Tendencies

Summing up, it is important to point out some of the main trends of development regarding governance in HE in Serbia. The biggest changes (resp. the longest arrows) happened in the dimension of state regulation and competition. As we already elaborated, state regulation has significantly decreased (especially in last 5 years) since the adoption of the new reform-oriented Law on HE in 2005. The Law fully complied with Bologna principles and result was: less direct state regulation. It gave HEIs more academic freedoms and autonomy to decide upon internal organization and budget allocation. If we take NPM as the ideal model, this change can be perceived as a progress, a positive development. And, in reality it had positive consequences for HE, such as establishment of buffer bodies and introducing quality assurance system. However, decrease of state regulation had some negative aftereffects – strengthening of academic self-governance. Very often on opposite sides, state and academics are dominant in governing HE. The state has the role in defining the shape of the system through laws, while curves of the everyday life at the university are drawn by the academics (through statutes of universities and faculties).

Considering the entire previous analysis of HE, we find that the main reason for this inconsistency of developments (taking NPM benchmark) is the lack of accountability of HEIs in Serbia. Although present, the quality assurance system is still weak to go one step further and become quality enhancement system. HEIs are still untouchable Ivory towers.

Competition on quasi-market is the second dimension that significantly increased in HE in Serbia. As explained, the competition is still underdeveloped and quasi-market is emerging. It can be expected that this trend will keep increasing due to globalisation processes and perspective of EU accession. We see this as a positive development mainly because it can lead to lowering of the Ivory towers. The Strategy mentions, but does not elaborate on development of the performance-based funding or importance of efficiency in spending and allocation of scarce resources.

Less visible changes happened in dimensions of stakeholder guidance and managerial governance. Due to struggle between academic self-governance and state, and their overall dominance, there is still little space for stakeholders’ involvement and managerial decision-making. We believe that the main obstacle lies in difficulty to overcome the communist legacy. Society that was oppressed by one political party is used to perceive any actor from ‘the outside’ - outside of profession or sector - as political control and threat to autonomy. This specific mind-set is the reason, we believe, for impossibility to fully apply NPM principles in the present HE system in Serbia.

3.2 Different Opinions

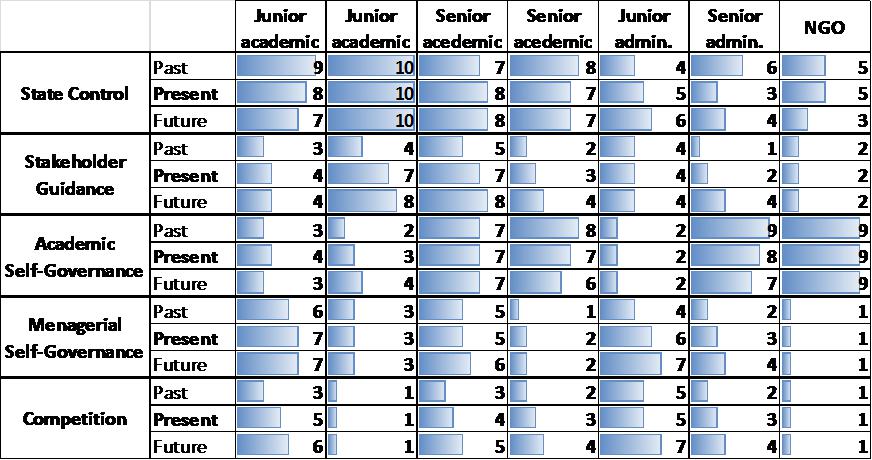

In order to explore the possibility of perhaps different opinions, we have created a small questionnaire (see Appendix 1) related to the Governance Equalizer and sent it to several contacts in Serbia. The aim of the questionnaire was not to serve as an opinion poll, but rather to provide an additional perspective. Participants were asked to estimate the influence of five governance dimensions on the scale 1-10 (1 minimum, 10 maximum) on HE system in past, present, and future. There was also space for comments where they could elaborate their opinions and experiences.

We have received 7 answers in total: 2 from university administrative staff, 2 from junior academic staff, 2 from senior academic staff and 1 from Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) dealing with HE issues in Serbia. The results are presented in the Figure 4 below.

Figure 4: Different opinions

Although it would be hard to draw general conclusions based on such small sample, we did notice some trends. With regards to state regulation it can be noted that junior academic staff have perception of extremely high state control which they explain as a result of past tendencies. Senior academics also give higher importance to the state primarily due to its financial role. Other opinions fall more or less in line with our projections.

In the dimension of stakeholder guidance there is less divergence of opinion but noticeably academics have somewhat higher perception of stakeholder inclusion, which can also be explained by their background (can depend on their faculty).

It was very interesting to notice that junior academics recognize much lesser level of academic self-governance than their senior colleagues, who are also mostly part of the academic oligarchy and therefore have more knowledge on inner workings of the system. For junior academics the main actor, obviously, is the state and the role of academics is second stringer. It is also interesting to point out the difference in opinions between the junior and senior administrative staff, which can be explained by the lack of relevant experience.

When it comes to managerial self-governance it would be important to point out that different faculties can offer different perspectives and thereby influence the opinion of poll taker. Generally, moderately higher scores for Menagerial Self-Governance in most of the answers can be noticed.

Results for the competition dimension are similar across the board. We would like to address to two opinions in particular - one junior academic and the NGO. In the opinion of the junior academic the reason for low competition lies in the fact that Serbian universities are not integrated. This stands in line with our analysis, that defragmentation creates unproductive competition based in authority (‘quasi competition’). On the other hand, we cannot say that ‘quasi market’ is present, rather emerging (in the way that de Boer et al. defined it). Similar is the opinion of NGO that do not believe in existence of any kind of ‘quasi market’ due to the fact that Bylaw that regulates funding of public universities has not been changed and the current one does not promote competition. In their view private universities have too small market share to be considered serious contenders.

Overall, we do not think results were that surprising, but no conclusive remarks can be made due to small sample size. We believe that a more elaborate questionnaire on this matter could shed new light and help us better understand the governance of HE in Serbia.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we reflect on previous analysis of HE system in Serbia through several points.

First, we find governance equalizer, as an analytical tool, extremely helpful for better understanding of the way the HE system works. It offers five, quite different perspectives in examining the same phenomenon. It also helped us realize the interconnection and the mutual dynamics of these dimensions. We came to realization that usually the movement in one dimension resonates in other four. How will the sound (the change) resonate depends mainly on the resonance box (HE system) and the settings on the equalizer (governance forces). Tuning or equalizing the audio frequencies (governance forces) is crucial for producing good music (more quality in HE).

Second notion is that any process of change takes time. Serbia has a long way to go in order to overcome the communist legacy and consequences of war. While overwhelmed by the specific mind-set we mentioned, NPM ideal, as de Boer et al. defined, is practically impossible to reach. The main holdup is the lack of accountability in HE on every level. However, governance equalizer helped us detect some changes, which means that situation is slowly improving. Establishing quality control system, recognizing the potential of entrepreneurial university and opening to EHEA are some of the shining examples of improvement.

At the end, this analysis has answered some questions, but raised new ones.The recognized changes are mainly connected to democratisation of society. On the other hand, Bologna process has had a huge influence on HE. The question remains whether these changes are the result of Bologna process, the influence of NPM ideas, Europeanisation or globalisation processes. Most probably, the answer lies in the combination of all four, but that is a subject of some future research.

References:

Birnbaum, R. (2000). Management Fads in Higher Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bylaw on norms and working standards on public-financed universities and faculties/ Uredba o normativima i standardima uslova rada univerziteta i fakulteta za delatnosti koje se finansiraju iz budžeta 2002 Službeni glasnik RS, br. 015/2002.

Clark, R. B. (1983). The higher education system: academic organization in cross-national perspective. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

CAQA - Commission for Accreditation and Quality Assurance Database, Retrieved 7. 11. 2013 from: http://www.kapk.org/index.php?lang=en

De Boer, H., Enders, J. & Schimank, U. (2007). On the Way Towards New Public Management? The Governance of University Systems in England, the Netherlands, Austria, and Germany. In: Jansen, D. (Ed.). New Forms of Governance in Research Organizations. Disciplinary Approaches, Interfaces and Integration. Dordrecht: Springer. pp.135-152.

Erlanger, S. (2000, October 6). Showdown in Yugoslavia: The New Face; Serbia's Reluctant Revolutionary Calmly Looks Beyond the Chaos. New York Times, Retrieved 23. 11. 2013 from: http://www.nytimes.com/

Ginsberg, B. (2011). The Fall of the Faculty. New York: Oxford University Press.

Jarić, I. (2009). Uslovi rada nastavnog osoblja na Univerzitetu u Beogradu: odnos prema upravi (The working conditions of teaching staff: relation toward management). Filozofija i društvo 3/2009, Retrieved from: http://www.cep.edu.rs/media/files/uslovi%20rada.pdf

Industrial production in Europe 1990-2012, comparison of countries/ Industrijska proizvodnja u Evropi 1990-2012, poređenje zemalja (2013). Retrieved from: http://www.makroekonomija.org/industrija/industrijska-proizvodnja-u-evropi-1990-2012-poredenje-zemalja/

Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development Database. (2013). Retrieved 7.11. 2013 from: http://www.mpn.gov.rs/

Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (SORS)/Republički zavod za statistiku (RZSS) (2013). Retrieved 23. 11. 2013 from: http://webrzs.stat.gov.rs/WebSite/

Strategy of Scientific and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia 2010-2015 (SSTDRS)/Strategija naučnog i tehnološkog razvoja Republike Srbije 2010-2015. 2010 Službeni glasnik RS, br. 13/2010.

Strategy on Education Development in Serbia until 2020/Strategija razvoja obrazovanja u Srbiji do 2020. godine 2012 Službeni glasnik RS, br. 107/2012.

Studentska unija Srbije (SUS), (c. 2011) Analiza stanja u oblasti studentskog organizovanja, učestvovanja studenata u procesu odlučivanja u telima visokoškolskih institucija i implementacije studentskih servisa sa aspekta Studentske unije Srbije. Retrieved 26. 11. 2013 from: http://projects.tempus.ac.rs/en/project/783

Law on University/Zakon o Univerzitetu 1998 Službeni glasnik RS, br. 54/98.

Law on higher education/Zakon o visokom obrazovanju 2005 Službeni glasnik RS, br. 76/05, 100/07, 97/08, 44/10, 93/12 i 89/2013.

Ziegele, F. (2008). Budgeting and Funding as Elements of New Public Management. Unpublished study material, University of Oldenburg.

Appendix 1: Governance equalizer questionnaire

Source: de Boer ,H., Enders J., Schimank U. (2007) On the Way Towards New Public Management?

The Governance of University Systems in England, the Netherlands, Austria, and Germany in: Jansen, D. (eds.): New Forms of Governance in Research Organizations. Disciplinary Approaches, Interfaces and Integration, Dordrecht, Springer, 135-152

Governance equalizer comprises 5 dimensions: state control, stakeholder guidance, academic self-governance, managerial self-governance, and competition. In ideal case put in the article by de Boer at al. State control should be on low level (2), as well as academic self-governance. Other dimensions are set higher (7-8).

Instructions: give estimate of past, present, and future situation in Serbia (1 minimum, 10 maximum) and mark with „X“:

-

State control refers to regulation by directives, i.e. detail prescriptions from the government for behavior under certain circumstances. Here authors denote the traditional idea of top-down authority vested in the state. For example financing, quota setting, legislation etc.

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

Past 2000-2012 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present 2012-2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Future 2014-2018 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Commentary (2-3 sentences):

-

Stakeholder guidance dimension concerns involvement of other actors through goal setting and advice (for instance, intermediary bodies or industry representatives). In public university systems the most important stakeholder is government, but not necessary the only one. For example buffer bodies, ex-ante or ex-post control, industry inclusion, student inclusion.

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

Past 2000-2012 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present 2012-2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Future 2014-2018 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Commentary (2-3 sentences):

-

Academic self-governance speaks about the role of academia and professional communities in HE systems. Their role is institutionalized through mechanisms like peer review-based self-steering of academic communities or collegial decision-making at universities. For example power of bodies such as Senate, councils.

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

Past 2000-2012 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present 2012-2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Future 2014-2018 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Commentary (2-3 sentences):

-

Managerial self-governance concerns organisational hierarchies at the university level – regulation and decision-making of the university leadership (rectors and deans). For example performance agreements.

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

Past 2000-2012 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present 2012-2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Future 2014-2018 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Commentary (2-3 sentences):

-

Competition within and between universities for scarce resources (personnel, finances or prestige) doesn’t involve real market. Rather, it is, so called ‘quasi-market’, where customer demands are replaced with performance evaluations by peers.

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

Past 2000-2012 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present 2012-2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Future 2014-2018 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Commentary (2-3 sentences):

Commentary (2-3 sentences):