Quality Management E-book

The Holy Grail: Learning Lessons to Nigeria from Research Quality Evaluation Systems in the US and the UK

Patricia Akamp

Abstract

By exploring impact studies of quality assessments and accreditation systems relative to the improvement of research outcomes of higher education institutions (HEIs) one can have a better understanding of the current situation and to some extent analyse what aspects of different models are vertically scalable (that is, for developed and developing countries). This paper looks at two successful models where research has been fostered: the US and the UK. It draws from their experiences and look for learning lessons which can serve as inspiration to other countries going through the process of designing their own research evaluation systems. In this case the study looked at Nigeria and concluded that the most important lesson it can take from the US and UK research evaluation system is to understand the rationale used in order to implement such models, and contextualize such rationale to its own priorities in order to develop a sustainable vision and define its place in the knowledge economy.

Key words: research evaluation systems, market-driven, state-led, developing countries.

Introduction

Following the new public management model in the late 70’s (Gruening, 2001), business-like quality assessments such as Total Quality Management emerged in the 90’s (Morgan & Murgatroyd, 1994). So around late 80’s, early 90’s a few countries started to implement business-like quality evaluation systems in the education sector. To explore research quality evaluation systems in this light is important because (ideally) this is the process that checks and classifies the value of all new knowledge produced by (HEIs within) a state, providing the much needed benchmark data with which a state can situate where it stands in the knowledge economy. What does it mean to lag behind in the knowledge economy? In economic terms the quaternary sector is the most advanced sector of the economy and the one to be expanded, so performance is a must. “Quaternary industries arise from breakthroughs in science and the outcome is social transformation. Novel solutions to human problems are developed, and choice in the marketplace expands. With new markets, new business practices come into being and the dynamics of human relationships change as the new technology is taken into households.” (Anderson, 2002). Here, the new dynamics of the education sector where universities’ progression focuses mainly on academic rankings to meet government funding criteria are less important than the potential that quality assessments hold as a supporting tool for development. Thus this paper aims to answer the following question: Considering the pros and cons of each approach: the more market-driven (US) vs. state led (UK) to research evaluation what are the lessons to be learnt for less developed countries with low levels of preparedness to implement research evaluation systems (Nigeria)?

Methodology

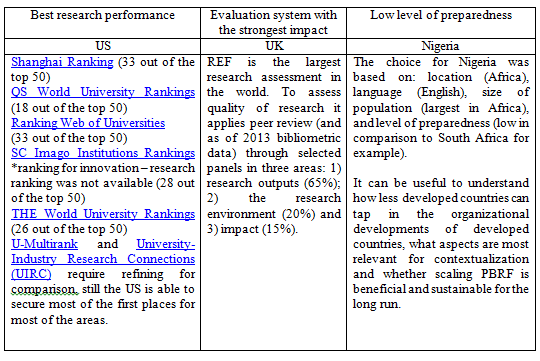

I will use the case study method to assess the two approaches, focusing on the US, UK and Nigeria. Through review of literature I will develop a comparative rationale between the countries while addressing the concerns outlined above about research quality performance. The choice for the UK, the US and Nigeria attempted to represent the best research performance, strong state regulation and low preparedness (please see Table 3 for more detailed explanation on the choice of each country). My analysis will rely upon primary and secondary sources. To understand the creation and implementation of state led research evaluation systems, such as PBRF, the study drew on the New Managerialism theory (Deem, 2011) (competition, output oriented, etc.) and Principal-Agent theory (with quasi-market incentives aligning research production to the principal agent’s interest).

Literature Review

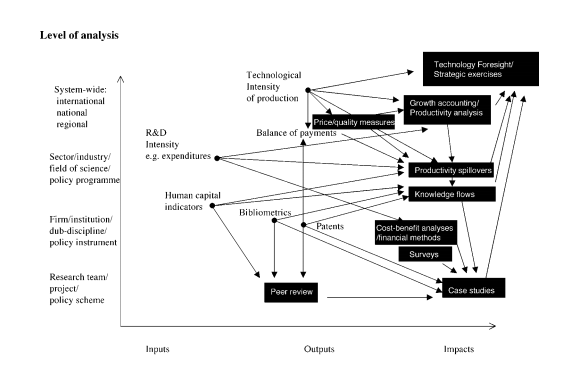

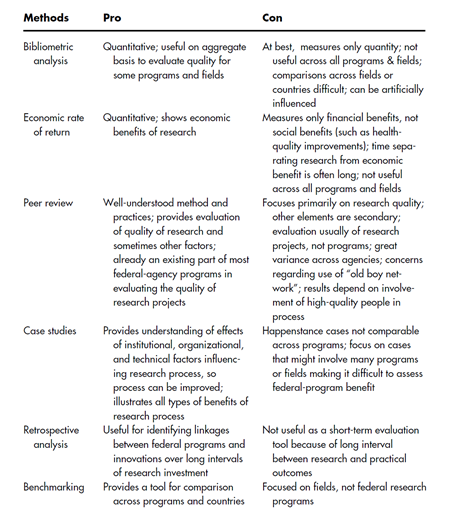

Research evaluation systems, as part of evaluation assessments in the HE sector, first took place in the US. The US has pioneered the methodology and different measurement approaches in the analysis of higher education (even as a new field of study). Rankings started as early as 1925 and the initial system was used until the 50’s, ending in 1959 when peer review came to existence. Funding allocation, among other awards and developments, were allocated according to such reviews. However since the 80’s OECD members started adopting indicators as part of their research evaluations and funding allocation (Sanyal, 1992). Please, see Table 1 at Appendix for an overview of evaluation indicators and techniques for research and Table 2 for an overview of pros and cons of each methodology. Performance based research funding (PBRF) is the most contentious system among all research evaluation systems, the one of highest state regulation. Yet it is increasingly being adopted by developed countries hence it is worth to analyse this model more closely. Through literature review it became clear that there are two main general views on PBRF: as a state control tool and as a quality enhancement tool.

Performance-based research funding as a state control tool: marketization of academia

According to the literature review these are some of the main disadvantages of implementing PBRF system: high cost; may lead to homogenization of research; may discourage more risky research; may encourage ‘publication inflation’; may encourage ‘academic’ research; separates research from teaching; rewards past performance; may lead to excessive government ‘interference’ (Iorwerth, 2005); the design of PBRF is based on cost-benefit calculations which can imply governments decide how much complexity is worth the cost (may lead to a not optimal design); may discourage interdisciplinary research; may discourage potential new areas of research; may diminish national and cultural identity; may diminish broader societal and economic outcomes from research and overall, it may diminish novelty, innovation, intellectual diversity (Hicks, 2010).

Performance-based research funding as an enhancement tool: adding value to the scientific society in general

Scholars often associate the adoption of state regulation on research quality with the new public management approach. According to the literature, some of the benefits of state regulation on research evaluation are: a) increased productivity; b) stronger market influence, c) citizen oriented; d) stronger institutional autonomy; e) strengthening the state capacity to formulate, evaluate and decide education related policies; f) output oriented leading to .transparency and accountability (Hicks, 2010) (Kettl, 2000). Also, some advantages of PBRF found in the literature are: meritocratic; improve individual and institutional performance; competition may lead to increased efficiency; encourages research to be properly finished and disseminated; public accountability for government funds; encourages explicit research strategies; provides mechanism to link research to government policy; concentration of resources enables best departments to compete with world leaders (Iorwerth, 2005); introducing contestability to encourage research; excellence as defined by the academic elite (Hicks, 2010).

Research evaluation systems: the UK and the US

The three common ways by which HEIs are connected to their supporting networks (be it the government or the private sector) is through accountability, trust and markets (Iorwerth, 2005). In the US for example, the main link is the market, so HEIs are accountable and report on their research quality and productivity to their customers and partners (students, parents, alumni, and institutional partners) to build or maintain a relationship of trust. On the other hand, for EU members, including the UK, states are still responsible for most of HE funding for research and so, their main link is trust (through public funding). Yet accountability is also high here because these are advanced democracies and public opinion exerts a strong influence on political decision making. Meanwhile, in Nigeria for example, despite the fact that the main link is also trust (public funding), other variables come to play, such as corruption. Trust on the government is low and the state is generally not as accountable to the public. Also the demand for public institutions is much higher than the offer and the private sector is not as regulated as in developed countries, which leads to an unhealthy market competition (quality is disregarded here). In addition, when looking at the nature of quality, the perception of quality in HE in developing countries still tend to be that quality is exceptional (a more traditional notion of quality), rather than one that nurtures quality culture (Harvey & Green, 1993).

US: a market-driven research evaluation system

The higher education system in the US is mostly composed of universities (degree granting institutions) and colleges. As of 2013, it had with approximately 7234 HEIs, of which 4706 degree granting institutions, 1738 2-years colleges and 2968 4-years college (U.S. Departament of Education, 2015). When the US government issued the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) in 1993, requiring that all federal agencies developed a 5 year strategy plan, measuring and reporting on their activities annually (COSEPUP C. o., 1999), a domino effect started to formalize the state policies related to research grants to HEIs (as concerns over audits and further review were raised). The open discussion led by the Committee on Science, Engineering and Public Policy (COSEPUP) in 1999 was reflective of the public discourse in academia and the views on how research should be evaluated: considering the differences between basic vs. applied science. According to COSEPUP the most effective way to evaluate research quality is through expert review, including different methodologies such as: quality review, relevance review and benchmarking to determine levels of quality, relevance and leadership. However, the framework for research evaluation in the HE sector in the US is more market driven and to measure and evaluate research quality performance in the US is difficult. “[Though] input control is exerted in academia, a formal periodic performance control on the basis of defined criteria (output control) is not widely used. Rather universities, such as Harvard, use the performance management method of relying on the basic principle of a thorough selection of qualified scholars (by a rigorous use of academic standards)” (Ringelhan, Wollersheim, & Welpe, 2015).

Similar to Canada, the US national government does not control the operation of HEIs, yet it does ensure the marketplace remains healthy for a productive competition among institutions. Federal funds are available for private and public institutions through open competition and regulation is strong. It is in the hand of each HEI to decide which groups of researchers (individuals or groups) deserve the opportunity to join the competition, these usually are sheltered and sponsored to do so. In a mixed system private universities and public universities (in their majority owned by their state) compete individually, however alliances are encouraged for such research proposals (as it builds competitive advantage and so, teams develop naturally, as it should be in a highly competitive and yet healthy, free market). The impact of politics is stronger on public institutions and of course, politics vary from state to state, some exert more direct control and others have a more developed regulatory framework, taxpayer support (and subsidies) also vary depending on the state. Hence a HEI in a state will experience a unique level of research evaluation depending on the different regulations it has to undergo (Capaldi, Lombardi, Abbey, & Craig, 2010).

United Kingdom: quasi-market incentive (state regulation through PBRF)

The HE profile in the UK includes app. 90 universities, 40 HEIs (teaching and research) and 22 colleges (mostly teaching) (De Boer, et al., 2015), it seems small in comparison to other countries, but the economic impact from this sector is paramount to the British economy. Such importance is clearly understood from the model adopted in the UK, where the government exerts a stronger role creating a quasi-market environment. Jacob succinctly explains the rationale of funding as incentives in research evaluation systems (Jacob, 2011) :

“The initial logic underlying science policy dictated that competitively allocated funding would focus on strategic priorities, collaboration and so on while block grant funding would be used to promote capacity building and basic research (Weinberg, 1963, 1964; Rahm et al., 2000; Stokes, 1997; Guston and Kenniston, 1994; Jacob and Hellström, 2012). This logic also fitted with the linear model of innovation that was the dominant orthodoxy. Many industrially developed countries have, however, reduced the portion of R&D funding allocated in this fashion for a number of reasons. Chief among these is the desire to increase the capacity to steer research funding more directly and to couple public research to specific societal objectives. Some countries have chosen to retain direct institutional allocations, but to make some portions of this funding performance sensitive. Thus far, most of these seem directed at increasing publication output as, despite the prevalence of rhetoric about relevance and social impact, bibliometric measures still dominate impact evaluations of research (Bozeman and Sarewitz, 2011; IDRC, 2011).”

Research Excellence Framework: enhancing research quality ?

According to De Boer (De Boer, et al., 2015) the effects of REF since its inception can be explained through three stages:

- Selection: REF has gradually excluded funding from nationally-recognized research levels, nationally-excellent research levels, internationally-recognized and finally internationally-excellent research levels. Since 2012 only the highest levels (world-leading and world-class) have been funded.

- Concentration: As a result, quality related (QR) funding has concentred in fewer institutions. That means now 10 out of 130 institutions receive half of the HEFCE funding (1.6£ bi), the top 4 receive app. 30% of the total funds (but this percentage has also been increasing overtime). 9 institutions (Colleges) receive no quality related funding and 49 less than a million.

- Moderation: From the start RAE- REF has followed a trend that has ensured low funding fluctuation, so HEIs could plan themselves accordingly.

In addition, the impact of REF on faculty has been drastic, promoting competition to extremely high levels: in 1996, internationally leading departments accounted with 11% of the staff assessed, by 2001 the percentage had increased to 19%. Also, staff members rated as doing work less than nationally regarded suffered a sharp decrease, from 6,000 in 1996 to less than 700 in 2008 . This outcome was in alignment with the objectives proposed by REF and considered as a positive impact for the country, advancing UK position in the knowledge economy. Nonetheless, it can also be viewed as an indicator of how much “academic career mobility or ingression” this system allows for, with the approach of rewarding the best (and despising the rest). This not only contributes to the stratification of the research system, as it has economic implications in less developed regions, smaller cities and smaller institutions, but also reinforces social stratification in relation to research as a career choice for it is most likely only really wealthy students can afford education in the top HEIs. Regardless of REF’s social impact, most importantly, many scholars have questioned whether the quality of the research being produced has really been enhanced. As Moed (Moed, 2008) has eloquently posed, “[t]he use of citation analysis should be founded on the idea that citation impact, though a most useful and valuable aspect in its own right, does not fully coincide with notions as intellectual influence, contribution to scientific progress or research quality” . Leydesdorff (Leydesdorff, 2007) complemented his idea by explaining that “[p]ublications contain knowledge claims that compete for proving their value at the level of (one or more) scientific discourses. Citations can be considered indicators of diffusion at the network level and cannot inform us about the intrinsic quality of research at the site of production. Knowledge claims in publications provide the variation” (Leydesdorff, 2007). “The emerging knowledge-based economy may have more need to stimulate variation than to increase selection pressures.”

Nigeria: low preparedness

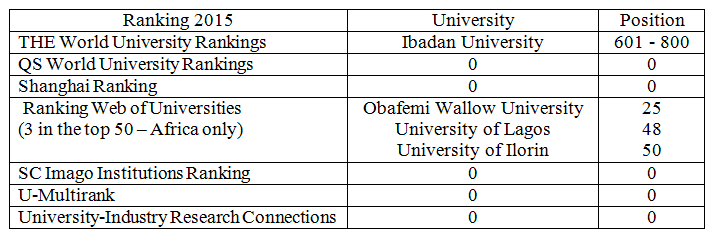

The higher education profile of Nigeria (as of 2013) had a total of 128 universities of which: 40 federal, 38 state owned and 50 private. In addition it also had 67 polytechnics and 92 colleges (Ogunkunle & Adekola, 2012). With a population of approximately 180 million people, 43% of those in the age range of 0-14 years old and 50% between 15-24 years old (CIA World Factbook, 2015), Nigeria will face intense massification of HE in the coming decades, especially as its economy grows. Ensuring quality will become a prime topic then. Currently, this is where Nigeria stand in the most well-known rankings:

Sources: The websites of World University Rankings, QS World University Rankings, Shangai Ranking, Ranking Web of Universities, SCImago Institutions Ranking, U-Multirank and University-Industry Research Connections (UIRC).

The rankings above are not determinants of Nigeria’s research quality, since we have discussed the misleading belief of a positive correlation between quality and publication/citation (even if of high impact). However, Nigeria’s HE sector is indeed performing poorly because HE has not been a priority in its government’s agenda. As in many developing countries, the provision of primary and secondary education (there mostly public) requires much of the funds allocated to education. Nonetheless accountability is not new in Nigeria, as of early 90’s universities already held external and internal evaluations of their academic programme, finance and HR management however research evaluation was not part of this model back then (Sanyal, 1992). Information about the model for research funding is not easily accessible, but literature indicates that most African states fund research through block grants to HEIs. In the case of Nigeria, the government has established reference points for quality enhancement and academic benchmarks based on competencies. The government also promotes private public

partnerships (PPP) envisioning the advancement of research and the HE sector as a whole (Ogbogu Christiana, 2013).

Limitations

Access to structured information regarding the research evaluation system in the US by a government agency was not easily accessible. Updated information regarding the education system in Nigeria, and policies related to performance-based research evaluations was not easily accessible.

Analysis of findings and recommendations

PBRF systems have been adopted by 14 countries so far (De Boer, et al., 2015), so it is worth analyzing the rationale that has led many of these governments to adopt such model. For example, the UK was the first to implement this model in order to select where to invest its limited resources considering that research costs (in highly developed knowledge economies like the UK is increasing exponentially). However for example in other European countries such as Sweden the focus was on international positioning and in Spain the focus was to increase research productivity and diffusion nationally and internationally (OECD, 2010). All of these countries made their decision based on three main factors: research production status in the country, internal pressures and international positioning. Nigeria would benefit from similar analysis, taking a more conservative and pragmatic approach, looking where it is, where it wants to go and how its own research evaluation system could be designed in a way to assist its efforts to meet its visions and goals. Caution is paramount, since even developed countries fall pray of international influences and trends. Norway for example have tried for years to increase its investments in R&D to meet the standards set by OECD, comparing itself to Sweden’s performance without acknowledging the importance of private demand in the dynamics of a heavily based knowledge economy (Roll-Hansen, 2009).

As new fads come and go (Public Administration, New Managerialism, New Public Administration, Governance and so on) the sphere of evaluation systems is also absorbing many of these influences (Impact factor, Impact, etc.). While deciding which research evaluation model to use Nigeria must consider its long term vision, economic and social considerations, yet it must not ignore the fact that accountability and transparency – in any form, can help to build social trust, which is lacking and in some aspects non-existent. This policy opportunity cannot be underestimated as it can enhance the development of indigenous solutions to the local problems which could bring about high profit (i.e.: there is a growing surge of great profitable inventions in developing countries – reverse innovation).

In more practical terms, based on the US model, some learning lessons for Nigeria:

The government can develop evaluation model that enhances and foster reverse innovation (identify sectors, support local scientific communication and the culture of academic public, welcome media attention, support partnerships (PPP), foster Nigerian academic diaspora (i.e.: assessments could grade more points for programs of locals with leading Nigerian scholars abroad), encourage entrepreneurship. Parallel measures such as strengthening of its IP laws and scholarship programs to retain its brains would ensure sustainability.

Learning lessons from the UK model for Nigeria:

Since the most common reasoning for PBRF is research excellence, this model has a high cost and is not inductive to equity (encourage concentration) and diversity (does not afford broader goals). In the case of Nigeria though, a good aspect of adopting indicators only would be to increase productivity and diffusion of knowledge. In countries where academic publication is not a tradition this could be a productive exercise, if done in stages and offered steady and reliable funding incentives (a crucial aspect of the REF model in the UK). PBRF could also base on specific areas where research excellence could have compound impact and spin offs, based on Nigeria’s strengths. In Brazil for example, Petrobras and Embraer have been sheltered and nurtured and research quality in those areas of expertise have traditionally been under stronger regulation and scrutiny (even at undergraduate level for program accreditation – as a response of strong Professional Associations).

Conclusion

Research evaluation systems can take place in more state-led models such as the one in the UK or more market-driven models as in the US. Research evaluation systems are important tools to help governments to direct areas of interests and expertise. However, more market-driven evaluation systems are more concerned with the longevity and protection of a strong culture of basic research (which in the US approach, is perceived as a long term process and must be free from set targets common in PBRF). Both models are a good representation of how important a self-assessment is and how pre-existing synergies, the nature of a country’s main industries, the strength of its private sector and its economy history are important variables with direct impact in research outcomes. In both environments (US and the UK), the role of the government has been to strengthen its pre-existing strengths. Hence in the case of Nigeria, the high cost in more tailored research evaluation systems, the lack of a strong free market like in the US and its low preparedness may seem like impossible challenges to overcome, but Nigeria must look at them as opportunities. It is important to capitalize on successful rationales, and not necessarily adopt the same systems.

Appendix

Table 1. Overview of evaluation indicators & techniques for research

Source: (Kane, 2001) as cited in (Iorwerth, 2005).

Table 2. Pros and cons of current methods for evaluating research

Source: (COSEPUP C. o., 1999) p. 19

Table 3. Best performance, evaluation system of highest impact and low preparedness: US, UK and Nigeria

Glossary

Basic research: research that is successful when it discovers new phenomena, its social effect is the discovery itself making it quite independent as it poses and solves new problems, plays an enlightening role which relies on autonomy from politics and economics to perform (Roll-Hansen, 2009).

Applied research: research that is successful when it contributes to the solution of specific practical problems, the social effect of such is the recognition of those posing the problem (government, business, etc.), hence applied research has an instrumental role subordinate to politics and economics (Roll-Hansen, 2009).

References

Anderson, D. (2002). Biotechnology and the quaternary industrial sector. Australasian Biotechnology, 12(1), 21;

Busch, P. (2008). Tacit Knowledge in Organizational Learning. IGI Publishing;

Capaldi, E., Lombardi, J. V., Abbey, C. W., & Craig, D. D. (2010). The Top American Research Universities - 2010 Annual Report. The Centre for Measuring University Performance at Arizona University. Retrieved from http://mup.asu.edu/research2010.pdf;

CIA World Factbook. (2015). Nigeria. CIA. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ni.html;

COSEPUP, C. o. (1999). Evaluating Federal Research Programs: Research and the Government Performance and Results Act. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. Retrieved from http://www.nap.edu/catalog/6416.html;

COSEPUP, C. o. (2000). Experiments in International Benchmarking of US Research Fields. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Retrieved from http://www.nap.edu/read/9784/chapter/1;

De Boer, H., Jongbloed, B., Benneworth, P., Cremonini, L., Kolster, R., Kottman, A., . . . Vossensteyn, H. (2015). Performance-based funding and performance agreements in fourteen higher education systems. Centre for Higher Education Policy Studies - CHEPS (Report for the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science;

Deem, R. (2011). 'New managerialism' and higher education: The management of performances and cultures in universities in the United Kingdom. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 8(1), 47-70. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/0962021980020014;

Gruening, G. (2001). Origin and Theoretical Basis of New Public Management. International Public Management Journal, 1-25. Retrieved from http://eclass.uoa.gr/modules/document/file.php/PSPA108/4NPM%20origins.pdf;

Harvey, L., & Green, D. (1993). Defining Quality. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 18(1);

Hicks, D. (2010). Overview of models of performance-based research funding systems. In OECD, Performance-based Funding for Public Research in Tertiary Education Institutions (Workshop Proceedings). OECD Publisher;

Iorwerth, A. a. (2005). Methods of Evaluating University Research Around the World. Department of Finance;

Jacob, M. (2011). Research funding instruments and modalities: Implication for developing countries. Sweden: OECD & Lund University;

Jong, d. T., & Fergunson-Hessler, M. G. (1996). Types and Qualities of Knowledge. Educational Psychologist, 31(2), 105-113;

Kane, A. (2001). Indicators and Evaluation for Science, Technology and Innovation. ICSTI Task Force on Metrics and Impact. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.492.1800&rep=rep1&type=pdf;

Kettl, D. F. (2000). The Global Public Management Revolution: A Report on the Transference of Governance. Brookings Institution Press;

Leydesdorff, L. (2007). Caveats for the Use of Citation Indicators in Research and Journal Evaluations. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology;

Moed, H. F. (2008). UK Research Assessment Exercises: Informed judgments on research quality or quality? Scientometrics, 74(1), 153-161;

Morgan, C., & Murgatroyd, S. P. (1994). Total Quality Management In The Public Sector: An International Perspective. Philadelphia: Open University Press, 1994;

OECD. (2010). Performance-based Funding for Public Research in Tertiary Education Institutions: Workshop Proceedings. OECD Press;

Ogbogu Christiana, O. (2013). Policy Issues in the Administration of Higher Education in Nigeria. World Journal of Education, 3(1), 32 -38;

Ogunkunle, A., & Adekola, G. (2012). Trends and Transformation of Higher Education in Nigeria. Management, Leadership, Governance and Quality;

Ringelhan, S., Wollersheim, J., & Welpe, I. M. (2015). Performance Management and Incentive Systems in Research Organizations: Effects, Limits and Opportunities. In I. M. Welpe, J. Wollersheim, S. Ringelhan, & M. Osterloh (Eds.), Incentives and Performance: Governance of Research Organizations (p. 481). Springer;

Roll-Hansen, N. (2009). Why the distinction between basic (theoretical) and applied (practical) research is important in the politics of science. LSE - Contingency and Dissent in Science Project (CPNSS);

Sanyal, B. C. (1992). Excellence and evaluation in higher education: some international perspectives. UNESCO, International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP). Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0009/000944/094470eo.pdf;

Servellen, A. v. (2011). Measuring Tacit Knowledge inAcademic Researchers. Master thesis - University of Amsterdam;

U.S. Departament of Education. (2015). Digest of Education Statistics, 2013 - Table 105.50. National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=84;