MaRIHE Master thesis reader e-book 2016

Public Higher Education Institutions in Indonesia: A Paradox of Autonomy?

Marsela Giovani Husen

Background

Institutional autonomy, without a doubt, is one of the most significant attempts to reform the higher education system. According to CHEPS report (2008), institutional autonomy has rising in almost all countries. The only differences were their starting point and the degree of such changes in each countries. Furthermore, institutional autonomy is persistently argued as the most significant governance trend in higher education (CHEPS 2008; Eurydice, 2008; 2000; OECD, 2008).

This trend also occurs in Indonesia and autonomy has becoming the most controversial issue in higher education sectors (ADB, 2012). Obviously, it is difficult to manage the multifaceted system and extensive numbers of higher education institutions (HEIs) in Indonesia. As Moeliodihardjo & Basaruddin (2013) confirm, there has been an awareness amongst policy makers that Indonesian higher education system is too large to be managed in a centralized way. Many people believe that ‘decentralizing authority and providing more autonomy’ to HEIs seems to be the most appropriate approach for managing such complexity (ADB, 2012, p.1). In that, major initiatives in the last two decades have been revolving around increasing institutional autonomy in Indonesian HEIs. Some of the most controversial initiatives were the initiation of legal entity universities, restructuring of public funding mechanisms, academic and personnel regulations (ADB, 2012).

Even so, there is a very limited numbers of research seeking to address this issue. Publications about institutional autonomy in Indonesia are very scarce. Most studies discuss the topic indirectly, frequently under the governance reform studies or other related topics, such as: legal entity universities, institutional restructuring, funding mechanism, academic freedom, commercialization of higher education, etc. (Kusumadewi & Cahyadi, 2013; Koning & Maassen, 2012; Achwan, 2010; Susanti, 2010; Varghese, 2009; Fahmi, 2007a; 2007b; Sulistiyono, 2007;Wicaksono & Friawan, 2007; Nizam 2006). Moreover, the past studies have

not been sufficiently mapping the institutional autonomy in higher education institutions (HEIs) in Indonesia. Furthermore, in those limited numbers of research that exist, most of them only concentrates on the positive trend and successfulness of the enhancement of institutional autonomy in Indonesian HEIs, but only use the autonomous legal entity university as a case study. It almost to the point of exaggerating the changes and success. In reality, no one knows the real degree of such autonomy, especially public HEIs in general. Thus, this study has been designed, with the aspiration, to fill in this gap, as well as to offer an analysis of certain crucial aspects of institutional autonomy in Indonesia public higher education institutions.

The overall aim of this study is to investigate the real degree of certain crucial aspects of institutional autonomy in public higher education institutions in Indonesia. According to that, the main research question is as follows:

What is the real degree of certain crucial aspects of institutional autonomy in public higher education institutions in Indonesia?

This study will contribute to the development of the study of institutional autonomy in several ways. First, by providing an overview of institutional autonomy reform in Indonesia (what is driving institutional autonomy, policy initiatives, the resistance and the reform towards it). Second, by obtaining the input and explanation from the stakeholders and experts, mapping a detailed picture of the real degree of certain crucial aspects of institutional autonomy in Indonesian public higher education institutions. Third, offering a recommendations to enhance the institutional autonomy policy initiatives in the future. Last, acting as a reference for further studies on institutional autonomy.

Institutional Autonomy

Estermann and Nokkala (2009) defined institutional autonomy as “the constantly changing relations between the state and higher education institutions and the degree of control exerted by the state, depending on the national context and circumstance” (p1). According to this definition, the freedom which government gives to higher education institutions would qualify as institutional autonomy. This definition provides a broader perspective because it implies that institutional autonomy is a dynamic concept. First, it emphasizes the relation between the state and higher education institutions that is always changing. Second, the term ‘degree of control’

accentuates that institutional autonomy is not a fixed notion, yet, there is a stage in a scale or series. Third, it also highlights the important of context and circumstance. To underline this point, Estermann and Nokkala (2009) accentuated that “analysis of autonomy should not be done in isolation and requires that the broader context to be taken into account” (p.8).

Therefore, it requires a consideration on when and where the term institutional autonomy is being used. In other words, this definition underlines the dynamic and multidimensional notion of institutional autonomy, while at the same time emphasizes the importance of context to explain them.

As the purposes of this study are to investigate the real degree of certain crucial aspects of institutional autonomy in public higher education institutions in Indonesia, thus, the definition from Estermann & Nokkala (2009) is appropriate for this study. First, to explore the institutional autonomy reform means there is a need to grasp the context of the reform, which includes the higher education in Indonesia, the rationales behind the reform, and the institutional autonomy reform in Indonesian higher education institutions. Second, to investigate the ‘real degree’ of institutional autonomy means there is an understanding that the concept itself is not a fix notion. There is an awareness of a gap between formal autonomy and the reality. Actually, this is not a surprise, as talking about institutional autonomy is not only about the freedom that university will acquire, but also the freedom that government willing to give to the university (ADB, 2012). Indeed, this definition is well-suited for this study.

Analytical framework

To analyze the real degree of institutional autonomy in Indonesian public higher education institutions, this study will adapt the four dimensions of institutional autonomy from the European University Association (EUA) (Estermann & Nokkala, 2009), which are: organizational, financial, staffing, and academic autonomy. One thing to bear in mind is that these four dimensions do not explained all aspects of autonomy. Nevertheless, it will provide an idea on certain crucial aspects of institutional autonomy that can be used to answer the research question of this study.

Organizational autonomy refers to a university’s ability to determine its internal organization and decision-making process (Estermann & Nokkala, 2009). It includes the governing bodies, external stakeholders, procedure and requirement for the executive body at the university. First indicator is that university has the capacity to decide their own internal governing bodies or structures, which usually consist of a board or council, a senate, or both of them. The inclusion and selection of external members in governing bodies become another important indicators of organizational autonomy. The important matter is whether the university has the capacity to select its member themselves or there is another external party that decide it for them. Moreover, the external representation in the governing bodies could also provide a mechanism for an accountability, which is an important component for institutional autonomy. Another crucial indicators are related to the selection procedures and criteria, dismissal and terms of office of the leaders of the university, which consist of rector and vice-rector.

Financial autonomy refers to a university’s capacity to manage its internal financial matters and allocate its budget independently (Jongbloed, 2010; Estermann & Nokkala, 2009). In particular, it related to the type of public funding, and the ability to keep surplus, borrow money, own buildings and generate self-revenues. There are two types of funding which will be used in this study, which are: block grants and line-item budget. Estermann & Nokkala (2009) defined block grant as “financial grants which cover several categories of expenditure” (p.19). University that receives a block grant funding has the capacity to distribute and manage their internal allocation as they see fit, although some restriction may exist. Whilst, line-item budget defined as “financial grants which are pre-allocated to specific cost items and/or activities” (Estermann & Nokkala, 2009). Generally, the university has to propose and allocate their budget to several specific posts or items, then the government will provide the money according to it. Hence, university is not able to make changes to the decision regarding the allocation of the money, or under some strict regulations.

As a matter of fact, financial is a complex issues in regards to the institutional autonomy, as this dimension has a very strong relation to other dimensions. As an example, university’s ability to decide their staff’s salaries also depends on their capacity to manage their financial matters. In that, as CHEPS (2008) emphasizes, financial autonomy generally perceived as an important characteristic of autonomous universities.

Staffing autonomy refers to a university’s capacity to recruit and manage its human resources independently (Estermann & Nokkala, 2009). Specifically, the capacity to decide on recruitment procedures, staff salaries, dismissals and promotions. One important element on

this dimension is the status of the employees. If the status of the university’s employee is civil servants then it shows that university only has a very limited capacity to manage their human resources. The reason is because the complexity of civil servant status that affiliated with various parties, such as Ministry of Education, Ministry of Finance, and Ministry of Labour and Employment. Most of the time, there are strict regulations and framework regarding civil servants status, thus, leaving a very small room for university to recruit and manage their human resources freely.

Academic autonomy refers to a university’s ability to manage its internal academic affairs without interference (Estermann & Nokkala, 2009). It includes the capacity to decide on overall student numbers and student’s selection, introduction and termination of study programs, as well as the design content of degree programs. First indicator is the capacity to decide on overall students numbers without any interference. In fact, this indicator has a relation with other dimensions as well. As an example, the overall numbers of students will have an implications to a university’s finances. Next, the ability to select their own students is another important indicator. According to CHPES (2008), this is another complicated issues, as most of the time, there are exist some policies and procedures regarding the selection of the new students that historically rooted in many countries and it is difficult to change them. Another important indicators are the capacity to open and terminate a study programs. It is important because it usually related to a university’s specific mission. Whilst the ability to design content of degree programs is the basis of the academic freedom and makes it another substantial indicator of academic autonomy.

According to the explanation of the four dimensions of institutional autonomy, it is obvious that all of them are interrelated in some ways. Moreover, it is important to be aware that not all indicators have the same degree of importance. Take the ability to charge tuition fees as an example, for some countries like United Kingdom (UK), it is a very crucial element. However, this is not the case for the Nordic countries, who subsidize their education and provides free tuition fees. Again, it accentuates the importance of context to analyze the situation. As this dimensions will be used to analyze the real degree of certain crucial aspects of institutional autonomy in Indonesian public higher education institutions, hence, it is important to take the broader context of Indonesian situation and higher education system into account.

Research Methodology

The strategy that will be used for this research is a multiple case study. As explained above, the aim of this study is to investigate the real degree of the institutional autonomy, within the context of public higher education institutions in Indonesia. Nevertheless, there are three models of public higher education institutions (HEIs) in Indonesia: State-Owned Legal Entity (SOLE) institutions or autonomous universities, Public Service Institutions (PSIs) and Public Government Institutions (PGIs). Thus, this research will focus on gaining a deeper understanding of the real degree of institutional autonomy in those three cases of public higher education institutions in Indonesia.

State-owned legal entity (SOLE) is the most famous model of all the university. They always become an example and subject in many case-studies about the successful governance reform in Indonesia. Currently, there are 11 universities are under this status. The second model is Public Service Institution (PSI). PSI is a new concept for HEIs and rarely known in public. Nevertheless, this status has been given to 21 public universities. One fact about this model is that PSI is not a legal entity, in that, PSI is still part of the Directorate General of Higher Education (DGHE). Even so, they have a certain degree of autonomy. The last model, Public Government Institution (PGI) is basically the rest of HEIs in Indonesia. There are about 113 public universities, in that, majority of public HEIs are still under this status. Similar with the previous model, PGIs are still legally under the DGHE.

The in-depth semi-structure interview with an open-ended questions were used as the primary data for this study. Meanwhile, the secondary data consist of literature in Indonesian higher education reforms, official policy reports and documents, as well as previous studies on institutional autonomy in Indonesian higher education institutions.

Purposive sampling approach were used for this study. In purposive sampling, researcher select a several numbers of interviewees according to their expertise of the topic. The researcher use a heterogeneous samplings technique. The aim of this techniques is to gain a greater insight into the phenomenon. In that, a sample of six interviewees that consist of policy makers, higher education experts, and academics were selected. The interviewees were two former Director of Directorate General of Higher Education in Indonesia, two higher education expert, particularly related to institutional autonomy in higher education institutions, one former Rector of State-

Owned Legal Entity university, and one Vice Rector of Academic Affairs at public service institution.

Interviewing different stakeholders will allow the researcher to do the cross-comparisons of responses. Thus, provides a different perspective of the same phenomenon, institutional autonomy, to emerge. All of the interview took place from March 17 to 31, 2016 at Jakarta and Bandung, Indonesia. It conducted by a face-to-face interview. All of the interview will be recorded to ensure that the data analysis is based upon an accurate evidence. Then it will be transcribed and translated by the researcher.

In terms of analysis, qualitative data analysis process that proposed by Creswell (2007) was used for this study. The process consists of six steps for conducting analysis. The first step asserts the importance of organizing and preparing the data. The second step of the analysis process suggests the researcher to read through all the data and become familiar with it. The third step involved coding the data. The fourth step involved organizing all of answers and codes according to the dimensions. The next step in the analysis process is reviewing dimensions and generating the idea on how it will be presented in the finding section. As the last step in the data analysis process, the data will be interpreted to generate findings and results.

Key Findings

Again, this study investigated the real degree of certain crucial aspects of institutional autonomy at three model of public higher education institutions in Indonesia. A brief summary of the results is presented as follows:

Organizational autonomy

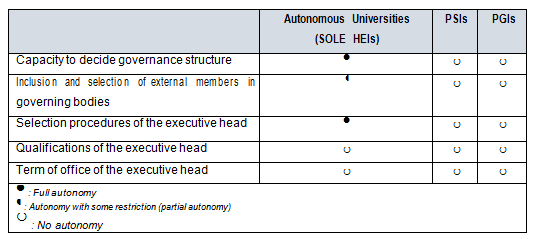

Out of five indicators, autonomous universities only have full autonomy in two of them: capacity to decide governance structure and selection procedure of the executive head. Whereas, they still do not have autonomy in another two indicators. Meanwhile, both PSIs and PGIs are still considered as part of the Ministry. In that, they do not have any autonomy related to the organizational matters. Organizational autonomy in Indonesian public HEIs is illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2. Organizational autonomy in Indonesian public HEIs

Financial autonomy

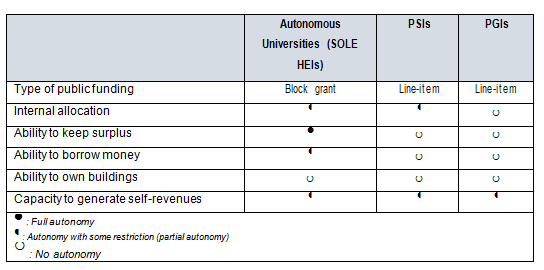

Table 3 exposed a lack of financial autonomy in in three models of public HEIs in Indonesia. There are restrictions and limitation in almost all indicators of financial autonomy. Despite receiving a block grant budget, autonomous universities only have full autonomy in 1 out of 4 other indicators (not include the type of funding), which is the capacity to keep surplus. Whereas, they still have no ability to own buildings. Further, both PSIs and PGIs have limited autonomy to generate self-revenues, however, only PSIs have some restricted ability to manage them.

Table 3. Financial autonomy in Indonesian public HEIs

Staffing autonomy

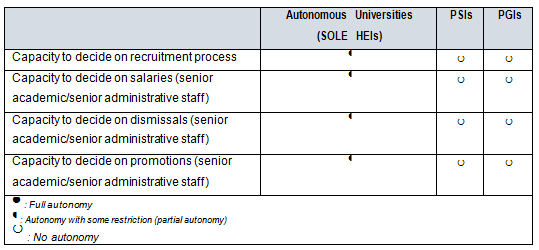

Staffing autonomy is the dimension with the lowest autonomy. There is an inadequacy of autonomy in three models of public HEIs. Both PSIs and PGIs do not have any autonomy related to the staffing matters. Whilst, autonomous universities only have a partial autonomy. They only have the capacity to manage their staff under the university employee track, but no authority at all to manage their staffs under the civil servant track. Unfortunately, most of their staffs are under the civil servant track. Table 4 illustrates the staffing autonomy in public HEIs.

Table 4. Staffing autonomy in Indonesian public HEIs

Academic autonomy

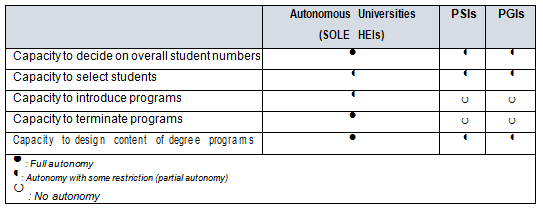

Academic autonomy, on the other hand, is the dimension with the highest autonomy compare to the other dimensions. Autonomous universities have full autonomy in 3 out 5 indicators, with only some restriction in other two indicators. Meanwhile, both PSIs and PGIs already have autonomy in at least three of the indicators, although some restriction may exist. Academic autonomy in Indonesian public HEIs is illustrated in Table 5.

Table 1. Academic autonomy in Indonesian public HEIs

Conclusion

Looking back at the findings of four dimensions of institutional autonomy, the real degree of certain crucial aspects of institutional autonomy in public higher education institutions in Indonesia as follow:

Levels of organizational autonomy is very low Levels of financial autonomy is low

Levels of staffing autonomy is very low. Levels of academic autonomy is medium.

Recommendation for future research

In regards to the limited availability of studies on institutional autonomy in Indonesia. This topic should be more researched to obtain a more in-depth knowledge related to it. As previously mentioned, this study only focused on certain crucial aspects of institutional autonomy, in that, future studies should expand in other directions or examine from different angles. Several feasible opportunities to advance this study are from the angles of the institutions, particularly a case study from the Public Service Institutions (PSIs) and Public Government Institutions (PGIs) that are basically non-exist at the moment; the barriers of institutional autonomy from both government and institutions perspectives; institutional autonomy at the private institutions that unfortunately are also insufficient; and the use of a more broad quantitative research could also be employed to quantify the changes of institutional autonomy across HEIs, nationally and internationally.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Ing. Johann Günther and Thomas Estermann for their support , guidance and suggestion throughout the entire process.

Bibliography

Achwan, R. (2010, October 19). The Indonesian university: Living with liberalization and democratization. Retrieved November 12, 2015, from Universities in Crisis: http://www.isa-sociology.org/universities-in-crisis/?p=767;

Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2012). Private higher education across Asia: Expanding access, searching for quality. Retrieved from http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/29869/private-higher-education-across-asia.pdf;

CHEPS (2008). Progress in higher education reform across Europe. Governance Reform. 1 Executive Summary and main report;

Cresswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed method research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage;

Estermann, T., & Nokkala, T. (2009). University autonomy in Europe I, the scorecard. Brussels: European University Association;

Eurydice (2008). Higher education governance in Europe: policies, structures, funding and academic staff. Brussels: European commission;

Eurydice (2000). Two decades of reform in higher education in Europe: 1980 onwards. Brussels: Eurydice;

Fahmi, M. (2007a). Indonesian higher education: The chronicle, recent development and the new legal entity universities. Bandung: Center for Economics ad Development Studies;

Fahmi, M. (2007b). Equity on access of low SES group in the massification of higher education in Indonesia. Bandung: Center for Economics and Development Studies;

Jongbloed, B. (2010). Funding higher education: a view across Europe. European Centre for strategic Management of Universities;

Koning, J., & Maasen, E. (2002). Autonomous institution? local ownership in higher education in eastern indonesia. International Journal of Business Anthropology. 3(2), 54-74;

Kusumadewi, L. R., & Cahyadi, A. (2013, June 29). The crisis of public universities in Indonesia today. Universities in crisis. Blog of the International Sociological Association (ISA). Retrieved March 06, 2016 from http://www.isa- sociology.org/universities-in-crisis/?paged=2;

Moelidihardjo, B. Y., & Basaruddin, T. (2013). Autonomy and governance in higher education. Jakarta: Analytical and Capacity Development Partnership (ACDP);

Nizam, N. (2006). Indonesia: The need for higher education reform. In M. N. N. Lee & S. Healy (Eds.). Higher Education in South-East Asia (pp. 35-68). Bangkok: UNESCO Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education;

OECD (2008). Tertiary Education for the Knowledge Society. OECD thematic review of tertiary education. Paris, OECD;

Sulistiyono, S. T. (2007). Higher Education in Indonesia at Crossroad. Nagoya: Graduate School of Education and Human Development;

Susanti, D. (2010). Privatisation and marketization of higher education in Indonesia: the challenge for equal access and academic values. Higher Education, 61, pp.209–218;

Varghese, N. V. (2009). Institutional restructuring of higher education in Asia. Paris: International Institute for Educational Planning;

Wicaksono, T. Y., & Friawan, D. (2008). Recent development of higher education in Indonesia: Issues and challenges. EABER Conference on Financing Higher Education and Economic Development in East Asia, 45. Bangkok;