Quality Management in Higher Education

In what ways students are really partners in quality processes?

Rebecca Maxwell Stuart

Introduction

Within today’s higher education systems, students are becoming increasingly important within quality processes. Catherine Bovill et al. (2011), defines students as being partners, and that their role is explained by being active and authoritative collaborators. This means that students are empowered to help influence decisions within pedagogical planning. Therefore this challenges the traditional hierarchies and roles of the professor and student, and this can sometimes cause academic staff to feel uncomfortable to ‘relinquish’ control. But by focussing on the positives through having a more democratic relationship which will overall enhance quality, this will hopefully overcome said issues. A shift in culture is needed in order to create an atmosphere of partnership and quality enhancement.

Students can sometimes be compared to consumers or customers. However, this does not allow for significant engagement and can create barriers. It could even be argued that the term apprenticeship is more suitable than partnership as how do students know what is right for them before they have mastered the subject field that they are learning? However, this essay will consider in what ways students are partners, rather than consumers, and how they can make an impact and enhance quality processes within universities.

In the QAA UK Quality Code for Higher Education, Chapter B5 is on student engagement, which highlights the areas that students can be involved and help to develop quality practices in HEIs. It indicates that there are several aspects of education that students can offer insight into. These are as follows:

- Applications and admission

- Induction and transition into Higher Education

- Programme and curriculum design, delivery and organisation

- Curriculum content

- Teaching delivery

- Learning Opportunities

- Student support and guidance

- Assessment

As is shown, student engagement is a hot topic in the UK, as well as in other countries. The reason for this is that engaged students can lead to a better quality of higher education. This indicates that students are, and can be, key players in improving the quality of institutions, through active partnership. Collaboration with students is important, because students can always have an opinion on how things could be improved, and what works and what doesn’t.

Students as Partners in Curriculum Design

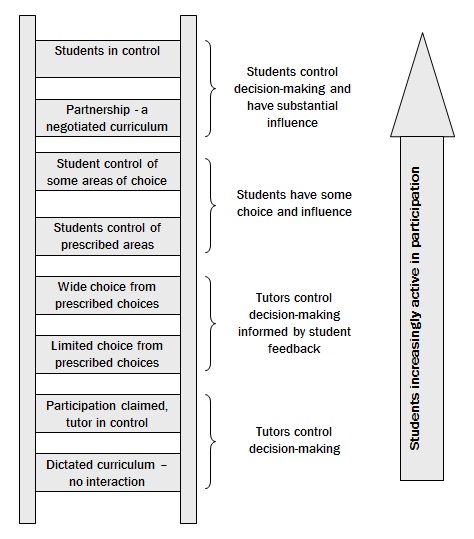

One form of practice that students can be involved as partners is through curriculum design: Bovill & Bulley (2011) created a diagram to show the different levels of student participation in curriculum design (see Figure 1). It indicates that an increased level of engagement can mean greater control from the students on the actual content of the curriculum. As mentioned earlier, academic teaching staff can find the notion of students in control as being chaotic and uncomfortable. Students do not always want to have complete control, as they have come to university to learn from their teachers. However, by giving them a say into the decision-making, this increases their commitment to the course, and thus gives them ownership of their own and their peers learning.

Figure 1: Ladder of Student Participation in Curriculum Design (Bovill & Bulley 2011, p.181)

An example of students in control of curriculum design can be shown through the work at the University of Sydney, where a module was created that students had to design and evaluate (Giles et al., 2004). The students found the project to be useful and helped them gain knowledge of the evaluation process. Additionally, the teachers found that students provided an invaluable input; which was creative, thoughtful and competent. This research shows that by involving students as partners during evaluations helps to develop their professional skills. While most evaluations are designed by academic staff, the study showed that students were given responsibility for creating and evaluating an online module. This innovative practice indicates that by giving students more responsibility it will benefit not only them, but their teachers as well through helping design future modules and improve quality which will lead to greater student satisfaction. Harvey & Green (1993) further address the notion of transformative quality and the importance of student empowerment. If students are given responsibility for the quality of their education, then they will have greater incentive to participate as partners in quality measures.

Following on from this, Zineldin et al. (2011) analysed student’s perceptions of quality in Turkey using a 5Qs model (quality of atmosphere, infrastructure, object, processes and interaction). They found that one of the critical components of quality was the responsiveness of the professors to students’ needs and questions. What can be seen is that students want a high level of interaction between the professors and the student body. This evidences that students would prefer a greater level of engagement with the curriculum as shown in the examples already noted in this paper. Also, it could be stretched to highlight that students now demand a greater level of communication, which can be achieved through a partnership approach.

Student Feedback

Student feedback questionnaires are commonly used as an evaluation tool. However, researchers have questioned the impact that this method has on teaching improvements. It can be argued that student feedback questionnaires are not effective because they are often standardised and the feedback loop is often not closed (Kember et al. 2010). This is further emphasised by other researchers who say that it is not always clear how fit for purpose questionnaires are (Williams & Cappuccini-Ansfield, 2007) or that they are not being used to their full potential (Harvey, 2003).

Powney & Hall (1998) further addressed the problem with questionnaires by saying that in order for there to be true partnership between HEIs and students, there is a need for closing the feedback loop. This means that after students have provided feedback about learning and teaching, there is a strong need for institutions to communicate how they have used this information to change, create and enhance. If the ‘loop’ is not closed, then students will not see the value in providing their feedback on university practices, and hence this will have an impact on quality enhancement.

Additionally student feedback can support decision-making as Richardson (2010) emphasised in his research that student feedback can be used to inform decisions on improving teaching quality. But again, like other researchers, he emphasised that just simply collecting feedback will not lead to such improvements; there is a need to close the feedback loop in order to strengthen an institutions accountability to prospective and current students. However, the main issues with teachers and institutions not using student responses can be the interpretation of said feedback, institutional reward structure, the publication of feedback (eg closing the feedback loop) and a sense of ownership of feedback on the part of both teachers and students. The last point signifies that when institutions receive feedback they can sometimes keep this to themselves, rather than publicise it and therefore nothing will happen. This again, shows that in order for a partnership to occur there needs to be clear communication.

It should also be stated that students are currently being asked to fill in so many surveys, and the chance of survey-fatigue is high. Hence, institutions need to think of more innovative ways to attain feedback, and by giving students ownership of the quality of their education is a way to do it.

Student Representatives

Student unions and associations are another mechanism in which students can be involved in quality measures. These representative bodies work in partnership with universities to improve and sustain the quality of education for students. Through individual meetings with senior academics, campaigning on issues such as exam bunching, and by being members of academic committees, they help to give a voice to students. Universities, who proactively work with student representative bodies, allow for the capture of the educational experience of all students. As student unions represent the entire student population, they are able to help shape decisions that will benefit the overall community. Harrison (2012, p54) summarises this engagement when she says: “In the spirit of partnership, institutions need to make greater use of the ongoing dialogue with students through both formal meetings and informal contact, to enter into a continuous conversation with students about the student experience and how to enhance it.”

Student Charters versus Student Partnership Agreements

Student charters are on the rise in English institutions. These are prescriptive instruments to show what students can expect from staff and the university, and what is expected of them. Unlike partnership agreements, charters set out minimum standards, and do not allow for a partnership approach. As Harvey & Green (1993) indicate, they have little impact on improving or even maintaining quality. Charters are a piece of paper that many students will forget, after reading and will only be called upon if something goes wrong. The QAA’s Chapter B5 emphasises this in their definition of partnership:

“Partnership working is based on the values of: openness; trust and honesty; agreed shared goals and values; and regular communication between partners. It is not based on the legal conception of equal responsibility and liability; rather partnership working recognises that all members in the partnership have legitimate, but different, perceptions and experiences… [it is a] mature relationship based on mutual respect between students and staff.”(QAA, 2012, p.3)

One method that involves students as partners is the newly developed Student Partnership Agreements that many Scottish institutions are implementing. Student Partnerships Agreements are a list of around five key priorities for student associations and institutions to work on for a certain period of time. Unlike student charters, they define opportunities for student engagement effectively (Williamson, 2013). Sparqs helped to develop guidance on creating partnership agreements so that they have two sections:

· Section A is mainly descriptive, outlining different ways in which students and staff can work together to bring about change.

· Section B is more practical, where it outlines areas of work that institutions and student associations will work together.

It falls in line with Chapter B5 of the QAA UK Quality Code in that it can help identify areas of student engagement. Unlike student charters, it does not resemble a contract, but helps to aid monitoring of student engagement, quality enhancement and promotes quality processes to students. Therefore they are more improvement-led rather than accountability-led mechanisms of engaging students in quality processes (Sea Law, 2010)

Conclusions

The idea of viewing students as partners is a multi-faceted area within higher education. It is argued that students can be change agents when it comes to learning and teaching practices at institutional and national level.

This essay has looked at the use of questionnaires and how they should not be seen as the only method to attain feedback from students. And this is definitely not part of the partnership approach. Rather, use questionnaires to begin the dialogue with students either before or after dissemination in order to create quality enhancement.

Rachel Wenstone (2012) argued that the goal of students as partners is not for students to just become co-creators of knowledge, but co-creators of the university itself. This can relate back to the Bologna University in history, where students gathered together to learn and led the way to creating the higher education system as it is today. Students played such an important part back then, therefore by having students as partners today; it allows them to be contributors to the overall quality of higher education. In order for there to be a true partnership between staff and students, there needs to be a strong level of communication as highlighted in this study, through such mechanisms as curriculum design and evaluation; and Student Partnership Agreements. Allowing students to be partners will shape quality processes into enhancement-focussed rather than just assuring quality.

“On a whole, there has been the realisation that in order to improve the quality of the educational experience institutions need to take account of the experiences, attitudes and opinions of those who are on the receiving end of the education- the students – and enhancement is a partnership approach.” (Harrison, 2012, p. 57)

References:

Bovill, C. and Bulley, C.J. (2011) A model of active student participation in curriculum design: exploring desirability and possibility. In Rust, C. Improving Student Learning (18) Global theories and local practices: institutional, disciplinary and cultural variations. Oxford: The Oxford Centre for Staff and Educational Development, pp176-188.

Bovill, C., Cook-Sather, A. & Felton, P. (2011) Students as co-creators of teaching approaches, course design, and curricula: implications for academic developers, International Journal for Academic Development, 16:2, pp. 133-145.

Gibbs, G. (2012) Implications of ‘Dimensions of Quality’ in a market environment. Higher Education Academy; York

Giles, A., Martin, S. C., Bryce, D. & Hendry, G. D. (2004) Students as partners in evaluation: student and teacher perspectives, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 29:6, pp. 681-685.

Harrison, T. (2012) Gathering student feedback: How can it make a difference? In: EUA (2013) How does quality assurance make a difference: A selection of papers from the 7th European Quality Assurance Forum. Belgium

Harvey, L. & Green, D. (1993) Defining Quality, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 18:1, pp. 9-34.

Harvey, L. (2003) Student Feedback, Quality in Higher Education, 9:1, pp.3-20

Kember, D., Leung, D. Y. P. & Kwan, K. P. (2010) Does the use of student feedback questionnaires improve the overall quality of teaching? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 27:5, pp. 411-425

Powney, J. & Hall, S. (1998) Closing the Loop: The Impact of Students Feedback on Students’ Subsequent Learning. University of Glasgow: The SCRE Centre

QAA (2012) Chapter B5: Student Engagement. In: UK Quality Code for Higher Education.

Sea Law, D. C. (2010) Quality assurance in post-secondary education: the student experience, Quality Assurance in Education, 18:4, pp. 250-270.

Richardson, J. T. E. (2005) Instruments for obtaining student feedback: a review of the literature, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30:4, pp. 387-415

Wenstone, R. (2012) Five questions about students as partners. WonkHe: [online] http://www.wonkhe.com/2012/09/13/five-questions-about-students-as-partners/(15.11.2013)

Williams, J. & Cappuccini-Ansfield, G. (2007) Fitness for Purpose? National and Institutional approaches to publicising the student voice, Quality in Higher Education. 13:2, pp. 159-172

Williamson, M. (2013) Guidance on the development and implementation of a Student Partnership Agreement in universities: Sparqs

Zineldin, M., Akdag, H. C., & Vasicheva, V. (2011) Assessing quality in higher education: new criteria for evaluating students‘ satisfaction, Quality in Higher Education, 17:2, pp. 231-243