Quality Management in Higher Education

Quality as power

Alfred Rafael Garcia

The world over, the discourse on quality in higher education has been constantly evolving to accommodate new meanings and appropriate new uses for the term, as much as the whole concept of ‘education’ itself has evolved according to the needs of the times. It is unmistakable to consider the idea of ‘quality’ as ‘what should be’ or ‘what ought to be,’ regardless of who decides on or sets the criteria on what is ‘quality education’. The buzzword in education at the global scene is ‘quality management’ which can be as polysemic in se as its root words imply. What is interesting, however, is to observe how the issue of education, and its quality included, has been appropriated on a political level.[i]

Harvey outlined several definitions of quality as they were understood during the specific time of their popularity, while expressing uncertainty as to whether these definitions are discrete or complementary in present usage (Harvey & Green, 1993; Harvey, 2002, p. 252). It should come as no surprise that the there seems to be a convergence between the definitions of quality post-‘quality as excellence’ with how quality is an operational concept in the business sector, as education itself has become more privatized over time.[i] This development has led to the proliferation of different instruments for the evaluation of quality, again governed in differing configurations by State and non-State actors, which influence HEIs on how quality is conducted in their business (Harvey, 2002; Harvey & Stensaker, 2008).

The UNESCO, however, embraces all functions of education as contributive components in quality, in harmonizing global, national, regional, and local developmental goals,[ii] indicative of ‘fitness for use’, another borrowed term from market discourse, where quality indicators may be used by supranational, national, and subnational actors to gauge quality, depending on specific contexts. For the purposes of this paper, we can attempt to investigate whether or not Harvey’s definitions of quality are discrete, overlapping, or configurations of different definitions, with specific attention to the Philippines’ HE System in its institution of a developmental quality management framework harmonized with political goals.

Harvey’s discourse on quality

Harvey and Green (1993) have framed much of the critical literature on quality in higher education in their synthesis of its definitions through time, inextricably linked with what education is (or should be). Their thesis hinged on the relativism of quality as a concept depending on its users at a specific period of time. Various other authors have contributed additions and modifications to the list of definitions provided by Harvey and Green, but the original list is described as follows (Harvey & Green, 1993 qtd in Harvey, 2002 p. 253)

Figure 1 Harvey and Green’s definitions of quality

Each definition comes invariably with its own recommended (prescribed?) instruments for measuring quality. Harvey (2002) outlined the implications of the use of these instruments, including, but not limited to, the purpose and effects of evaluation from an institutional, i.e. internal, and external, e.g. via accrediting agencies, perspective. He further outlined the process through which evaluation operates, distinguishing between convergences and divergences between internal and external processes, and favored a more transformative approach to institutional assessment, i.e. focusing on the teaching and learning process as central to evaluation, which, he argues, can best be operationalized with an internal evaluation system.

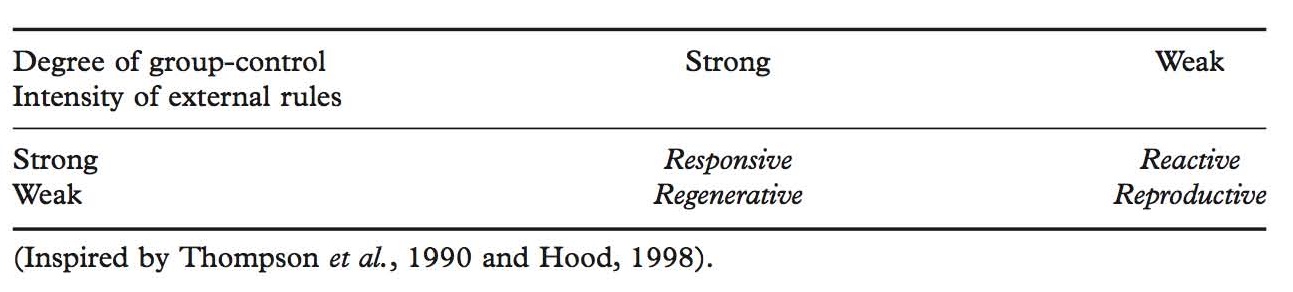

While evaluation as a whole became integrated in the (European) HE system with the name of quality assurance, it did not necessarily mean that quality was developed in individual HEIs. In a later work, Harvey and Stensaker (2008) argued for the incorporation of the practice of evaluation as an integral part of the core operations of an HEI, effectively arguing for the development of a quality culture, contingent on an individual HEI’s internal impetus in relation to external forces in an educational setting. He conceptualized these efforts into four ideal types, governed by two dimensions: degree of group-control or organizational ownership and the intensity of external rules (Harvey & Stensaker, 2008, p. 436).

Figure 2 Harvey's 'Quality Culture' ideal types mapped in a 'Cultural Theory' Framework

Quality as control

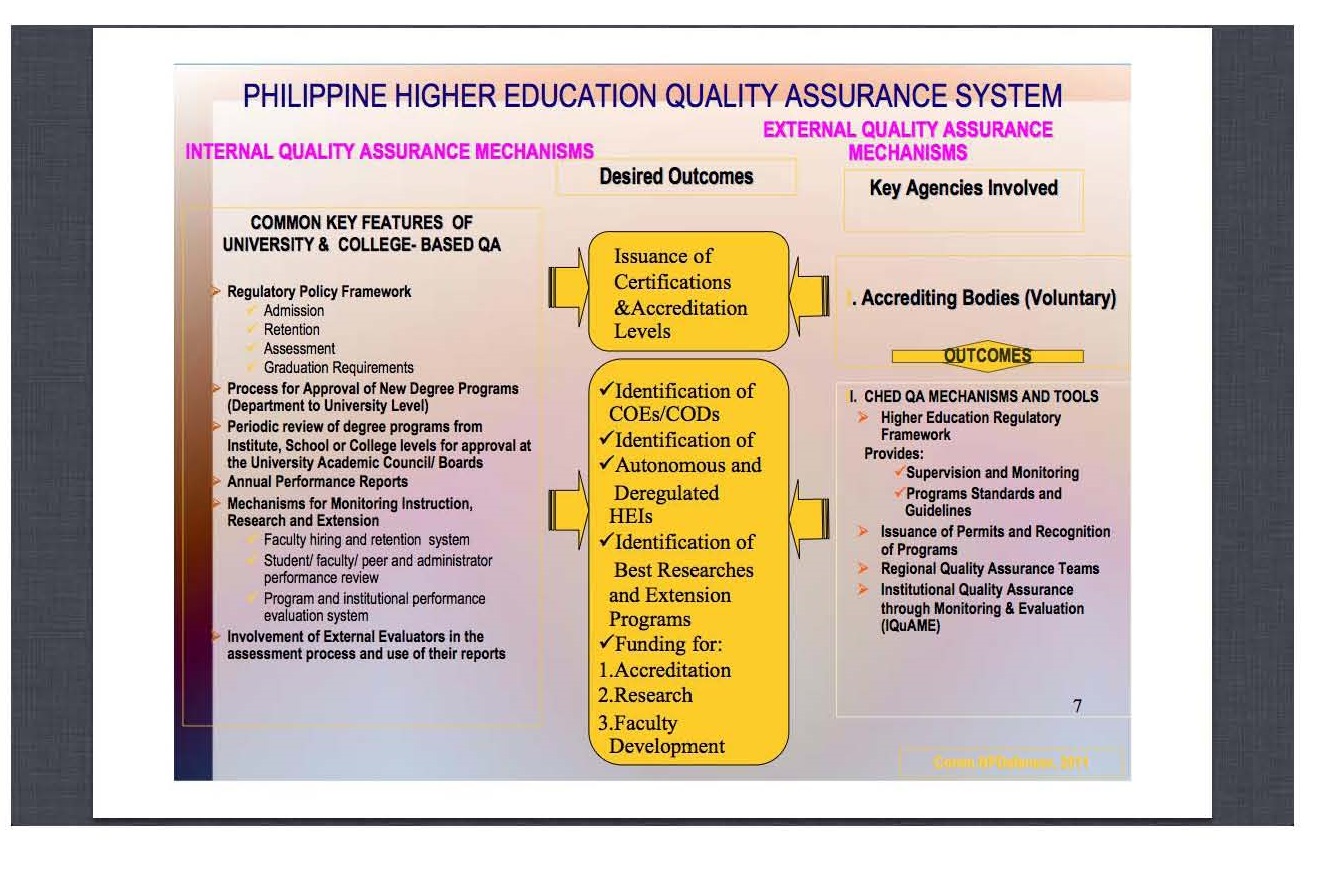

At least in Harvey’s rhetoric, quality has been consistently related with (if we can even say, ‘as a response to’) external controls, in as much as extracurricular factors directly or indirectly affect notions of quality, as well as the methodologies to measure quality. In Harvey’s Quality Culture framework, we assume that the degree of group control is exercised by the individual organization (HEI), and the rules can only be prescribed by agents who would have enough authority in designing and (strongly or weakly) implementing them: supranational and/or state-level actors, with their sub-national arms or their equivalents in the private sector, if any. In the Philippine Higher Educatoin System, the externality of regulatory frameworks comes from the Commission on Higher Education (CHED), which assumes policy control over all HEIs in the country.[i]

Framing the Philippine Discourse on Quality

In Smolicz’ (1999) work, he observed that:

“[w]ith its long established private sector, the Philippines has evolved both a formal and informal system of quality control for its institutions. The informal system is based upon the reputation that universities enjoy among the public, both on account of their perceived social status and their ‘track record’ in ensuring good employment prospects for their graduates. With regard to the formal system of evaluation, the system of accreditation has come to acquire an increasingly important role for private tertiary institutions. The unusual aspect of the system is that it is not compulsory, but self-imposed and voluntary.” (Smolicz, 1999: 208; italics mine)

SUC Autonomy and PHEI accreditation

The Private Higher Education Institutions (PHEIs), if accredited, enjoy varying degrees of autonomy from the State, represented by the Commission on Higher Education (CHED). It is interesting to note, however, that the State sanctions private accrediting agencies, recognized as one federation (Federation of Accrediting Agencies of the Philippines or FAAP), to evaluate programs and institutions. Public HEIs,[ii] however, are exempt from such a regulation, as the benefits of accreditation are already available to them. However, they are empowered to create their own quality assurance/quality enhancement mechanism, or in the absence of which, participate in these external procedures. All Philippine HEIs, however, are enjoined to abide by course Programs, Standards and Guidelines (PSGs), ‘internationally benchmarked’ minimum standards for the institution of programs outlined by the CHED (Commission on Higher Education, 2005; Congress of the Philippines, 1997).

In viewing Harvey’s auspices of external evaluation, Philippine accreditation as a practice has a non statutory dimension while the both the PRC and the COD/COE awards are statutory. These three elements are non-sectorial in nature, although all three functions may employ experts from HEIs. Formally speaking, all three operations should be independent from stakeholder influence, including the State. However, even the private sector FAAP submits itself to regulation/evaluation through a policy framework as laid out by the CHED, inasfar as the whole concept of accreditation and recognition are under the guidance of the State. [iii] (See Fig. 3)

The Institutional Quality Assurance through Monitoring and Evaluation

There is a strong State presence in quality assurance and a marginal one in quality enhancement. In 2005, however, it sought to affirm its role in both, with the institution of the IQuAME or the Institutional Quality Assurance through Monitoring and Evaluation, which, primarily, has a statutory, external, and sectorial dimension to QA. The purpose of the IQuAME is not to accredit HEIs (which remains at the sole competence of the FAAP) but to rate PHEIs according to what arguably seems like a vertical arrangement, from an informal perspective.[i] In a recent ruling, all FAAP-accredited schools are automatically granted an IQuAME rating, due to the ‘strong’ tradition of non-sectorial QA (Defensor, 2011; Institutional Accreditation and Assessment Office, n.d.; Philippines, 2008).

What is interesting is the (possibly superficial) difference between FAAP accreditation and the IQuAME, in as much as the former seeks to accredit, while the latter seeks to describe the current positioning of HEIs. What both have in common, however, are the (increasing) focus on outcomes-based evaluation procedures (in both academic and organizational affairs), as well the use of these instruments to justify prioritization in awards and grants, not to mention institutional ‘prestige’ that directly or indirectly comes with accreditation/rating. What is perhaps unique to IQuAME is its role as a developmental framework, where the criteria of the IQuAME are offered to (voluntary) PHEIs to operationalize their own institutional quality management system (IQuAMS), complete with indicators, while subsidiarizing the processes to individual institutions. (Defensor, 2011; Institutional Accreditation and Assessment Office, n.d.).

Quality as power

It is as this point where we see a full circle in the statutory IQuAME, and the institutional IQuAMS, if we consider that the IQuAME constitute external regulation and IQuAMS as the development (or reinforcement) of quality culture. We consider that the participation in either FAAP or IQuAME or voluntary, and are incentivized monetarily (through competition in grants/awards) or symbolically. We cannot imagine that there is an extremely strong severity in the State meta-instrument, given its voluntary and subsidiarized nature. We can only assume that the factor that will dictate ‘success’ in a quality management instrument of this nature is the level of “buy-in” of an HEIs faculty and staff to the indicators (as given by the State) and the processes and procedures to realize them (as operationalized by the HEI). As of the moment, only less than a hundred have been ‘rated’ by the IQuAME, and it is much a question between subsidiarity and ‘domestication of norms’ relative to Harvey’s Quality Culture Framework.

There is another factor to consider: the very idea of quality itself. The State, through the CHED, and through the IQuAME, appropriates upon itself the complementary definitions of quality as excellence, quality as consistency, quality as value for money (Commission on Higher Education, 2012: 3). The performance indicators of the IQuAME embody the performance of quality as excellence and consistency, while the ratings of the IQuAME itself will eventually lend weight to a State-proposed horizontal classification system for HEIs.[i] The move claims to harmonize educational policies on a national level, while adhering to global standards. This should not come as something particularly surprising, as the recent developments in CHED policy have seen further dovetailing of national, regional, and local governmental policies as educational goals, under the much touted buzzterm “nation-building”.

While certainly education theory can support the move of societal integration with curriculum development and higher education research, the question is definitely to ask if the nation’s very goals are appropriate to begin with. We see at this stage that the discourse of quality in education in measuring quality in terms of pedagogical, organizational, and societal indicators no longer rests in the rhetoric of education, but that of politics, and the power relations between State agencies defining the space of the discourse on quality, and the institutional agencies expected to manifest this notion of quality. The very idea of rationalizing HEI ‘quality’ as mandated by the State level begs the question, quis custodiet ipsos custodies?

References

Belfield, C., & Levin, H. (2002). Education Privatization: Causes, Consequences and Planning Implications. Paris: UNESCO: International Institute for Educational Planning.

Biglete, A. (2004). Philippines . In A.-P. P. Development, Handbook on Diplomas Degrees and Other Certificates in Higher Education in Asia and the Pacific (2nd edition). Bangkok, Thailand: UNESCO Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education.

Commission on Higher Educaiton. (2007b). Revised Implementing Guidelines for CHED REPUBLICA Awards. Retrieved October 26, 2012, from Commission on Higher Educaiton: www.ched.gov.ph

Commission on Higher Education. (2012b). Draft Policy Standard to Enhance Quality Assurance (QA) in Philippine Higher Education Through an Outcomes-based and Typology-based (QA). Retrieved September 9, 2012, from Commission on Higher Education: www.ched.gov.ph

Commission on Higher Education. (2005). Revised Policies and Guidelines on Voluntary Accreditation in Aid of Quality and Excellence in Higher Education. Retrieved October 26, 2012, from Commission on Higher Education: www.ched.gov.ph

Congress of the Philippines. (1994). An Act Creating The Commission On Higher Education, Appropriating Funds Therefor and For Other Purposes. Retrieved October 26, 2012, from Commission on Higher Education: www.ched.gov.ph

Congress of the Philippines. (1997, June 6). AN ACT PROVIDING FOR THE UNIFORM COMPOSITION AND POWERS OF THE GOVERNING BOARDS, THE MANNER OF APPOINTMENT AND TERM OF OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT OF CHARTERED STATE UNIVERSITIES AND COLLEGES, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES . Retrieved October 25, 2012, from The LawPhil Project: www.lawphil.net

Congress of the Philippines. (2008, April 29). AN ACT TO STRENGTHEN THE UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES AS THE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY. Retrieved October 24, 2012, from The LawPhil Project: www.lawphil.org

Defensor, N. (2011). Quality Assurance in Philippine Higher Education: The Role of IQuAME. Retrieved October 28, 2012, from The British Council: www.educationuk.org

Garcia, A. R. (2012). New Private Management: Governance Equalizers in Philippine Higher Education. Paper. Unpublished.

Harvey, L. (2002). Evaluation for What? Teaching in Higher Education , 7 (3), 245-263.

Harvey, L., & Green, D. (1993). Defining Quality. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education , 18 (1), 9-34.

Harvey, L., & Stensaker, B. (2008). Quality Culture: Understandings, Boundaries, and Linkages. European Journal of Education , 43 (4), 427-442.

Institutional Accreditation and Assessment Office. (n.d.). Primer on the Quality Assurance, Monitoring, and Evaluation of Higher Education Institutions. Retrieved October 28, 2012, from De La Salle University Manila: www.dlsu.edu.ph

Karseth, B. (2008). Qualifications Frameworks for the European Higher Educaiton Area: A New Instrumentalism or "Much Ado About Nothing"? Utbildning & Demokrati , 17 (2), 51-72.

Philippines, P. o. (2008). Subjecting Only Non-Accredited Private Schools For Institutional Quality Assurance Moitoring and Evaluation. Retrieved September 9, 2012, from The LawPhil Project: www.lawphil.net

Smolicz, J. (1999). Privatization in Higher Education: Emerging Commonalities and Diverse Educational Perspectives in the Philippines, Australia, Poland and Iran. Development and Society , 28 (2), 205-28.

UNESCO. (2001). Quality Assurance: World Higher Education Framework of Action. Retrieved November 9, 2012, from United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organizaton: www.unesco.org

[i] Where institutions will be grouped according to their current mandates and performance, such as universities for teaching and research, local colleges, and professional schools.

[i] Of which there are four categories: A(r), mature institutions of teaching and research; A(t), mature institutions of teaching; B, developmental capacity for teaching and research, and C, others.

[i] Cf. Garcia (2012) for the extent and limitations of CHED control over Philippine HEIs.

[ii] Composed of State Colleges and Universities (SUCs) and Local Colleges and Universities (LCUs). SUCs are regional institutions operated autonomously from, but are funded directly by, the State, while LCUs are funded by local government units such as cities and municipalities. (Biglete, 2004, pp. 224-225)

[iii] Cf. Commission on Higher Education, 2005

[i] Where privatization can loosely mean “the transfer of activities, assets and responsibilities from government/public institutions and organizations to private individuals and agencies” assuming ‘liberalization’ in government regulations and ‘marketization,’ i.e. the use of the ‘quasi-markets’ in public services. (Belfield & Levin, 2002, p. 19)

[ii] As per Article 11 of the World Conference on Higher Education Framework of Action (UNESCO, 2001)

Notes

[i] It has been noted that (European) policies have helped shape the educational landscape on a specific direction (Karseth, 2008, p. 52).